Doorable

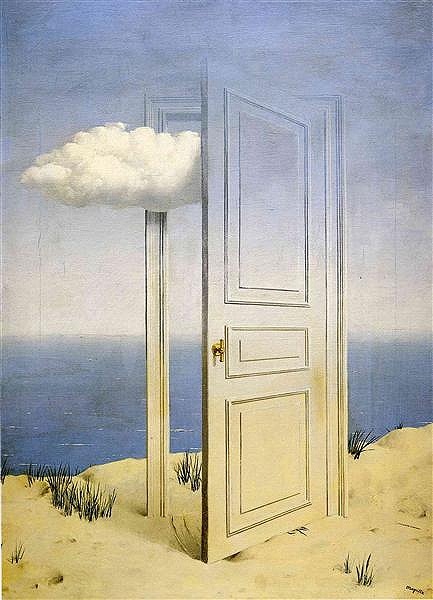

René Magritte: La Victoire (1939)

"I sign my name on the bottom of the ones I've finished just as if I was some famous artist or something …"

On my better days, I believe that everything in this world is here to serve as my teacher. On my best days, I actually catch myself practicing this foolishness. It's not mere foolishness, though, but one of those beliefs that to hold it makes it come true, which makes it a very special sort of belief, indeed. With a run-of-the-mill belief, both ideation and execution lie in the believer and perhaps a few fellow followers. It's a baby bubble operation that only works with considerable delusion. My belief about everything being my teacher requires no delusion and no more than a mustard seed of faith because it's really more about my acceptance of my role as student than about any teacher or lesson plan. One never knows what might become the subject of the next lesson or what might appear in the role of teacher, but only the willing student gains the benefit. ©2021 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

I am not universally recognized as a willing student. I'm actually much better remembered as reluctant to the point of defiant, and quite noisy when learning. I've developed skills capable of deflecting even the best intended lessons, especially anything smacking of being for my own good. I hate being told what to believe, which left me out of the sciences, which rely upon a delicate network of beliefs to exist and advance. And scientists must also be precise. No measuring in cubic furlongs when grams suffice. Science often seems to lack sufficient imagination to attract that much attention. Most subjects have been distilled down into stale dates and hollow portraits, ancients with one hand stuck into their blouse or posing with a sword or something. The practical arts like HomeMaking remain ambiguous. There are no credible must dos when repainting an interior, just some trusty guidelines eternally amended by context and emerging experience. When repainting, every surface might be the painter's teacher and every painter seems wise to accept their role as humble and appreciative student.

Mistakes always make themselves known.

This week, doors were teaching me. Well, doors and Curt our painter, who has clearly listened to many more doors than I've listened to over the years. Doors are as a class mostly silent. They speak when taken down off their hinges and also when, hinges reattached, one attempts to hang them again. They speak almost non-stop when being repainted. It must be like a trip to the dentist for them. They have their dings and cavities to explain. They, too, lie about flossing. They recline there just as they are, independent of their explanatory stories. They hold gouges like conservatives hold grudges. Their scrapes and scars speak mountains and seem daunting to anyone attempting a refinishing, a misbegotten term, since nothing associated with HomeMaking ever gets completely done. If it wasn't finished the last time, it cannot qualify for refinishing this round. Let's agree that we're actually seeking a resurfacing such that the door might appear more finished than before, that and a matching color. More finished doesn't demand doneness, just acceptance.

I entered my door work a little too full of myself, as if I already knew what only that specific door could ever teach me. I attempted dominion but found complications, unique combinations of the usual dings. I quickly exceeded my experience. Curt reassured me that I could resand and repatch through each successive coat, that the door and the paint could handle that, and that the objective was not perfection, but a rather modest illusion. Painting, he insists, is all about concocting visual tricks intended to convince a viewer than the finish is better than it actually is, or could ever actually be. Using little paint on inside surfaces struck me as subtle wisdom. "The millage doesn't matter inside," Curt opined, "Unless you're painting a high-volume industrial railing. On residential woodwork and walls, no more than just enough for color works best. On doors, even less." I imagined myself a Scrooge, doling out teaspoons of paint. I imagined my brush as more scraper than spreader, intended to leave little evidence that it ever visited, certainly no tell-tale brush marks. The door seemed to whisper a sign when satisfied. I just needed to listen.

Next I'll move on to windows which see everything and say very little. One reads windows without expecting them to confirm suspicions. They'll screech if I hit a tender spot and always remain capable of breaking their glass if not treated with gentle respect. Windows communicate to their more-finisher more by example than through words. They appreciate appreciations and respect. There are no damned windows, for instance, just damned painters. It's best when the respect remains mutual.

Days drag on, punctuated by paint drying breaks and unanticipated runs to Home Despot. To paraphrase Hilaire Belloc's famous works, A trick that everyone abhors in HomeMakers is sloppy doors. The key, it seems, comes from listening and listening as if you really didn't know, whatever you might have convinced yourself you knew before. Slip into that student's chair however small and impractical it might feel, prepared, if you can, to learn something amazing. It will be well worth whatever humility you invest. Later, once the place gets put back together again better than it ever was, that door might smirk when some visitor praises your work. I sign my name on the bottom of the ones I've finished just as if I was some famous artist or something, rather than a humble student still, eternally, learning his trade.