Imprecision

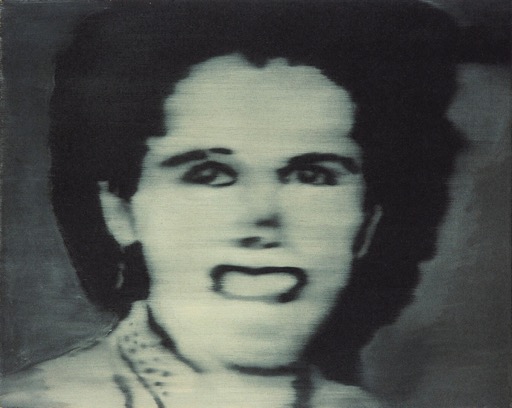

Gerhard Richter: Frau Marlow, 1964

" … revealing perhaps more than any of us care to recognize about reality and truth."

Back before the pandemic, when I could sometimes go out for morning coffee, the waitperson would often respond to my order by saying, "Perfect," as if we'd managed to achieve perfection together. I'd order my usual large (not Grande, thank you, or Venti … we are not in Italy and even in Italy, I chronically forget the proper word) decaf in a china cup and receive a "Perfect" in return. I'd noticed that this response had become common, so I was never surprised or shocked, but I remained curious about how such precision had entered into the most common of all transactions. It was "Perfect" here, "Perfect" there, and "Prefect" pretty nearly everywhere, while in what passes for real life, in ordinary times, perfection remained as it always had, slightly rarer than hen's teeth. ©2020 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

I figured that we might have forgotten how rare perfection always was and continues to be, as production values have exponentially increased. Watch a television production from the fifties and Ted Mack's Amateur Hour looks like a genuinely amateur production with light and sound shadows, and obvious mistakes prominently not edited out of the final result. Now, even the crappier productions appear flawless. Sure, sometimes the continuity gets tangled, but mostly, the actual production quality disappears, and the actors seem as though they're not performing, but living much more expertly than you or I. I'd stammer the occasional line and hem and haw a bit, but today's productions reveal none of this. Of course these same stars of big and small screen tend to live lives more flawed than any you or I could muster, but exclusively offscreen. Onscreen, they exude pure perfection, at least until the blooper reel runs at the end behind the overlaid credits.

Real life seems tenaciously imprecise. Most of whatever we accomplish, we manage to achieve without access to good or even good enough information. We don't know only because we cannot know, and yet we catch on early that we must somehow act anyway, in the absence of anything like perfect knowledge. We learn to estimate risk, though usually without any actual baseline against which to actually access. We rely upon notions, instead, often firmly based in belief indistinguishable to us from the most solid fact. Sometimes we guess wrong, but often we guess right, this universe tending to be more forgiving than we imagine, too. It's mostly guesswork, and even science utterly depends upon acknowledging and accepting this fact. Most of us non-scientists see little of science at work until after the designers have smoothed the ridges and the engineers have filed off the sharper edges. We mostly interact with tenaciously repeatable experiments like our car or our refrigerator, and never experience the great imprecision from which our apparently precision products emerged.

Then a novel virus appears. One with its rough edges still indistinct. Scientists speculate and postulate and initially produce disappointingly imprecise results. Great mysteries persist months after the bug first entered our into midst, and we grow impatient. I could approach perfection ordering a morning coffee, but our greatest minds can't seem to come up with the barest semblance of it when investigating something of actual significance. One after another description turns out to ring not quite true. Some say, "Screw this," and abandon all faith in science explaining anything, and fall back into their usual intuition which, after all, seems to have served them well enough so far. We remain in the dark, poking sticks, sometimes seeming to finally (finally!) get the hang of it until fresh data suggests that maybe we haven't found the handle at all. All the while, people continue to fall ill and some of the most seemingly unlikely even die. It's no wonder that some see only a hoax threatening them. Whomever produced this dang pandemic should lose their license to produce believable fiction.

I've long mourned the golden age of television, when reception was generally spotty and came exclusively in black and white on ten inch screens. Then, my imagination engaged to complete the glaring imprecisions, radio only once removed. Now, projections on even the smallest screen seem somehow more real than life, and I need to rely upon my imagination only to render believable what real life produces. Our pandemic response seems far from perfect, so far from perfection that to my modern acculturated eye, it seems unreal because it doesn't live up to anything like my expected production value. It's too messy to entertain me and seems to only misleadingly inform me. I feel no wiser after watching. I feel moved to further hunker down. I am most certainly not considering standing back up and wandering around with this phantom killer on the loose. Science plods forward and, fortunately for us, does not rely upon the overnight ratings for renewal. The Imprecision seems cruel and unfeeling, revealing perhaps more than any of us care to recognize about reality and truth.