OrdinaryTimes 1.47-Phorms

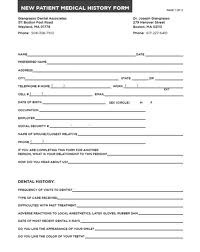

Last year, she dropped me off at her dentist, thinking that this act would pretty much guarantee that my excruciating cracked wisdom tooth would get looked at. She left, then they gave me a clipboard filled with blank forms. I couldn’t answer even half the questions. I went to the receptionist, explaining that I’d need to leave the office to get some information the forms wanted. Forty five minutes later, I was home digging through The Muse’s filing cabinet, trying to complete the forms. I did not find the information they needed. A couple of hours later, after The Muse emerged from another of her total isolation meetings, she called me, a little frantic. “What happened at the dentist?” she fumed. “I got a couple of calls wondering where you’d disappeared to.”

”They gave me forms,” I whimpered.

’Nuff said.

Some people don’t do forms well. Like me, they chronically misinterpret labels, thinking they’re beneath the lines rather than above them. I suppose this drives the data entry people crazier than it drives us. We don’t carry much arcane data around in our heads or our wallets, not even in our not-really-that-smart phones. We do not know our mother’s childhood cat’s nickname, a seemingly common question on medical history forms. We also never know our spouse and primary insured’s social security number, and remain uncertain of their exact birthdate. Back when I had a land line phone, I became slightly notorious for not being able to reliably remember my own home phone number, especially when an empty form loomed all scary before me. Now that I no longer have a home phone number, I can safely leave that space blank.

My phorms phobia might be related to why I don’t test well. I’m best at telling stories, and I perform terribly when expected to report only facts. This feels like I’m responsible for chewing someone else’s supper before they’ll agree to swallow it. It feels unseemly: gross, disgusting. Plus, I usually just don’t know. I have not populated my buffers with much more than impressions.

I can almost never find the proper insurance card, either. I know those cards hold much of the information these insidious forms want, but under the pressure of delivering, I can’t seem to find the damned things. I find the wallet card holding the password to that storage unit we abandoned nine months ago. (Gee, I thought I’d thrown that out.) A punch card from Grand Central Bakery in Portland. (Five more loaves and I get a free Como!) Several unused airline frequent flier cards, though I only infrequently fly. Look, there’s last year’s insurance card. Only The Muse can sift wheat from chaff and identify the proper ID.

She, though, holds much of this information in immediately accessible storage. She deftly grabs the clipboard and starts writing. I can always answer any question about how any ancestor met their demise, but I cannot find the proper line to register that information. Some consider my handwriting criminally illegible. The Muse serves as my seeing eye dog and together, we can complete any form. (“Ahem,” she notes, “They wanted your signature in that space, not your printed name.”) Damn, I did it again. (Alone, I’m sunk.)

Even with The Muse piloting, the completed form looks like it’s been filled out in finger paint once I’ve contributed my part. Without her, I cannot even achieve that meagre result.

I’m supportive of The Affordable Health Care Act, even though I recognize that it’s predicated upon a tenaciously upper-middle and upper class assumption, that any sentient being can fill out forms. This assumption, never explicitly stated or mandated, will likely be the unacknowledged straw that breaks this otherwise sturdy camel’s back. One very good reason to not have insurance has always been the opportunity to avoid failing to fill out forms.

The Muse has been after me for several years to go to a doctor for a check-up, but I’ve been successfully deflecting. Even if I managed to find a doctor willing to see me, a huge IF in an area where most every GP is in permanent ‘taking no new patients’ mode, I know I’d once again be handed that nefarious clipboard and I would once again find myself unable to remember my Mother’s childhood cat’s nickname. I still have no idea what that bit of data has to do with health care. Humiliated, then, I’d slink out the side door satisfied that I once again wasn’t quite qualified to see that doctor, either.

©2013 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved