Selz

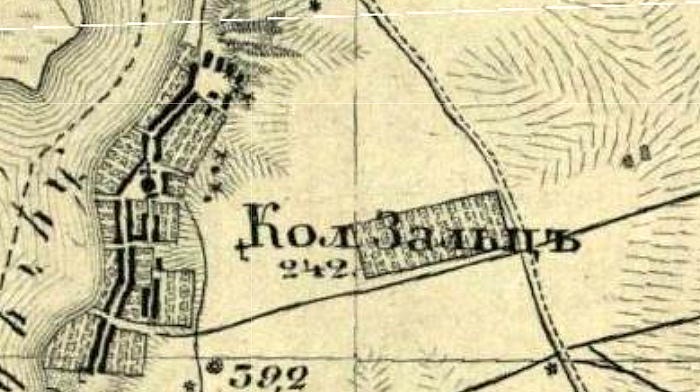

Kolonie Selz. Map by Alexander Ivanovich Mende (Mendt), 1853

"The city ceased to exist after it was evacuated during the Nazi retreat in 1944."

My fifth great-grandfather, Joseph (Josef) Schmaltz, was born on January 11, 1780, in Kapsweyer, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. He would die eighty years later in Kuchurhan, Odesa, Ukraine. My fourth great-grandfather, George Wilhelm Schmaltz, and his twin brother Heinrich "Henry," were born in 1804 in Germany. The family emigrated to Ukraine later that year, settling in a new town, Selz, in the Kutschurgan Valley, where the Kutschurgan River flows into the Djnester estuary, about forty miles from the district center, Odesa. This place was sandy river bottom land that melded into black prairie soil further from the river. They initially constructed rough brush huts, later building a substantial town complete with a large cathedral, a park, and extensive orchards.

Being German, much material has been passed down through the generations. Detailed maps of the town show the location and ownership of each home, and both Schmaltzes and Welks (my first great-grandmother's family—she was Lawrence Welk's aunt) are prominently represented. The family thrived, and the chance Alexander I and his grandmother Catherine II had taken when attracting Germans to settle this barren land paid off well, perhaps too well for the settlers. No trees greeted the first arrivers. Forty years later, they'd planted over four thousand, including thirty-five hundred fruit trees. The experiment thrived.

Then, Russia lost the Crimean War. This represented a profound shock to the Russian system. They'd been consistently winning wars against The Ottoman Empire for decades, but this one, characterized by some as the first world war, highlighted some systemic weaknesses in the Russian system. Their armies were comprised of reassigned serfs, essentially enslaved people, and their soldiers seemed to lack a sense of purpose. The Czar and the Parliament decided they needed to change the terms of engagement if they were to compete successfully in the emerging world.

Their solution involved freeing the serfs to work the land like the German settlers had. This, they reasoned, would give soldiers something to fight for, a sense of motherland. The resulting reforms sought to level the new playing field to make the newly freed serfs more equal to the German settlers. This initiative didn't grant the serfs the freedoms and privileges the Germans had thrived under but clawed back the rights granted in perpetuity to the settlers’ grandfathers. They reneged on the original deal. Henceforth, the Germans would be subject to conscription in the Russian army. They'd be subject to other Russian civil authorities. They'd lose their sacred autonomy. They were suddenly required to conduct all business in Russian, a language few settlers cared to speak. Some Germans would even be resettled into new colonies to teach the serfs how to emulate their success. These newer colonies were only sometimes located in places even as arable as the harsh Steppe surrounding Odessa had been. My family was not forcibly relocated, but the dream they'd built after being displaced from Alsace was undermined.

My first great-grandfather, Nicholas Daniel, Senior, left Setz in 1893, shortly after his first son, my great-uncle John, was born. He had persuaded his father-in-law's family, the Welks, to travel with him. They ended up in North Dakota, a country eerily similar to the land around Selz. Within a generation of that flood of Germans-from-Russia immigration, North and South Dakota replaced Ukraine as the world's breadbasket. Those who stayed behind were subject to conscription into the Russian Army, and many Russian divisions in the First World War were Germans fighting Germans. During the Bolshevik Revolution, the town suffered when revolutionary authorities turned their churches into granaries. Collectivization undermined generations of stewardship of the delicate farmland. Later, under Stalin's great purge in the early nineteen twenties, the entire region was further starved into even deeper submission. So many died that the census data from 1930 was suppressed lest it show the effect of the policy. Many were forcefully relocated to Siberia and Central Asia. Most of them were never heard from by family again.

Selz ceased to exist after it was evacuated during the Nazi retreat in 1944. The remaining German colonists welcomed the invading Germans. Before Operation Barbarossa began, under the non-aggression treaty Russia and Germany had signed, Germans had been targeted for voluntary repatriation back into Germany. The Nazis had even set aside a valley in Poland as suitable for relocation and began moving families there once they'd over-run Poland. The Nazi invasion of Russia upset those plans. Any remaining German settlers became suspect. Nazis promised to take Ukrainian Germans with them as they retreated, but Russian forces eventually overran those ungainly columns of refugees. Many of the Germans the Nazis vowed to relocate ended up in special relocation camps, essentially concentration camps. Fleeing Ukrainian refugees were sent to, you guessed it, Siberia or the Asian Far East. Russians claiming German heritage make up the seventh largest ethnic group in Russia today.

My Great-Grandfather would thrive in the new world, though he wouldn't stay in North Dakota for long.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved