AlmostRandomly

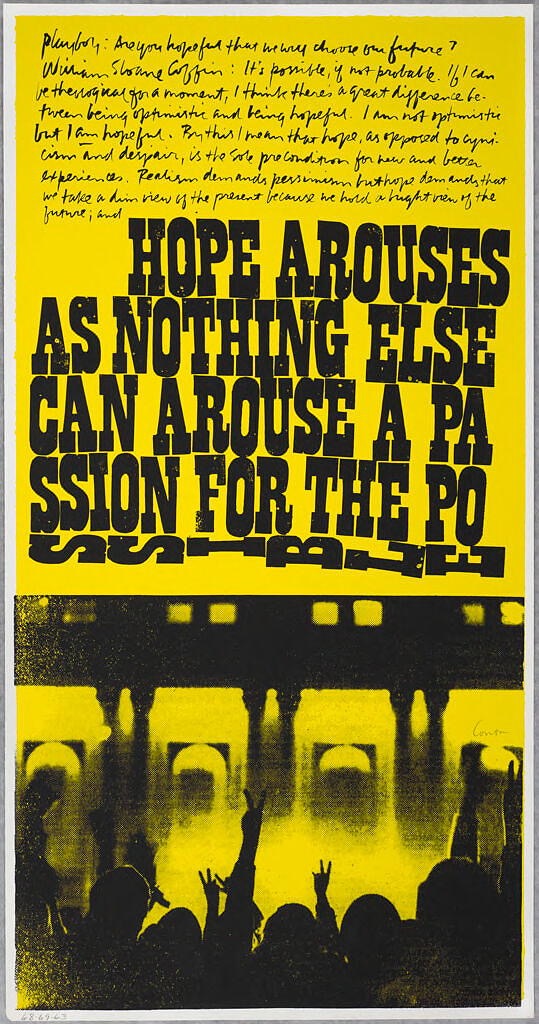

Corita Kent (Sister Mary Corita):

a passion for the possible (1969)

Inscriptions and Marks — Signed: l.r., within image: Corita

inscription: l.l., in graphite: 68-69-63

(not assigned): Printed text reads: Playboy: Are you hopeful that we will choose our future? William Sloane Coffin: It's possible, if not probable. If I can be theological for a moment, I think there's a great difference between being optimistic and being hopeful. I am not optimistic but I am hopeful. By this I mean that hope, as opposed to cynicism and despair, is the sole precondition for new and better experiences. Realism demands pessimism but hope demands that we take a dim view of the present because we hold a bright view of the future; and HOPE AROUSES AS NOTHING ELSE CAN AROUSE A PASSION FOR THE POSSIBLE.

"We continued searching AlmostRandomly …"

Our highest priority upon arriving in Exile became finding suitable digs. The Muse's employer had thoughtfully provided temporary housing through an Oakwood franchise, the sort of housing guaranteed to encourage short tenancy. I'd lived in an Oakwood property when working for a boutique Silicon Valley consulting firm fifteen years earlier. That was a sprawling two-story suburban affair ringing a swimming pool. This latest one was a fifteen-story highrise overlooking a firehouse. The swimming pool was situated out back behind security fencing and a thick hedge. Both were places that reeked of dislocation. I inhabited my Silicon Valley one four nights each week, baffling myself at the supermarket when failing to remember which refrigerator I was stocking. I'd invariably end up with too much and too little of some things because I could never keep my inventories straight. Our Arlington neighborhood of Rosslyn apartment wouldn't offer any such entertainment.

The apartment proved to be a definite downgrade from our usual and customary. The kitchen was suitably poorly appointed. The living room, spare. The bedroom and bath, barely there. The place provided ample encouragement to engage in the often disquieting search for some home out in that wilderness. Since The Muse was gratefully gainfully employed, I would become the pointy end of the search stick. Someone—I cannot remember who—had connected us to a realtor who provided us with leads loosely based on our preferences. We hardly had preferences at that point other than the often overwhelming one to return home. I was at least a reluctant explorer. On weekends, we'd travel out to the more remote locations, each of which eventually proved unsuitable. Our acceptance criteria matured as our search continued because there would be much we couldn't have imagined before we began. By then, we'd both been out of any real estate market.

I'd group the leads into neighborhoods. Like every big city, DC is a series of remarkably insular neighborhoods. Each carries its own caché. Park Slope is entirely different from Chevy Chase, though they are no more than a couple of miles separate. The quality of housing ranges from horrible to more than decent, often along the same street in the same neighborhood. Crime rates, always a concern for the visiting hayseeds, also vary almost randomly. What might appear a secure suburb might hold a much less than stellar reputation, so the realtor's recommendations held some water. We'd learn, though, that nobody can meaningfully direct any such search. It requires feet-on-the-street engagement. It's not necessarily even the house but the context that defines acceptability. I chose to get lost walking neighborhoods.

I used the bus. This tactic enabled me to learn how to use the bus, an essential skill if one's attempting to live in any urban area. Relying solely on cars exacts a steep sentence. I was looking for a location where The Muse could commute by Metro or bus, and I could leave the car parked at home when running errands if I wanted. The traffic there was, at best, hostile and often much worse, so I held the availability of public transportation as a non-negotiable. I'd take the bus to one side of a neighborhood, then head off on foot to reach the other side. I'd weave my way, trying side streets as well as arterials, talking to people I'd meet on the street, and trying to understand the locals. This was a terrifying effort. It challenged my introversion, but then the Oakwood Hospitality Association was breathing down my neck every second. Also, The Muse's new employer had set a reasonable time limit on how long they'd tolerate picking up the tab for the temporary lodging. The only thing worse than staying in that sorry apartment was the prospect that we might have to pay for the privilege of staying there. We searched, scared.

I rejected almost every neighborhood out of hand. The few that made it through my initial perusal I'd introduce The Muse to over the weekend. She would dispatch those that I hadn't. The more far-flung locations quickly fell because of one or another commuting Hell. We were insistent that an hour each way commuting would not prove sustainable, though several of The Muse's coworkers maintained such a schedule for years. The more urban areas also largely failed to attract us. We were not apartment-building people. We had outdoor cats. We needed some sort of a yard. The more romantic-sounding areas like the backside of Capitol Hill, perfect logistically, proved impossible realistically. Imagine a row house five yards wide with a stairway no wider than two and a kitchen so small that the refrigerator could only fit in the adjacent dining room, which, once holding the fridge, wouldn't be large enough for a dining table. We gravitated toward a separate single-family house that was relatively close in. We continued searching AlmostRandomly, slowly learning what we wanted as we came to appreciate what our new context offered.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved