BigPicture

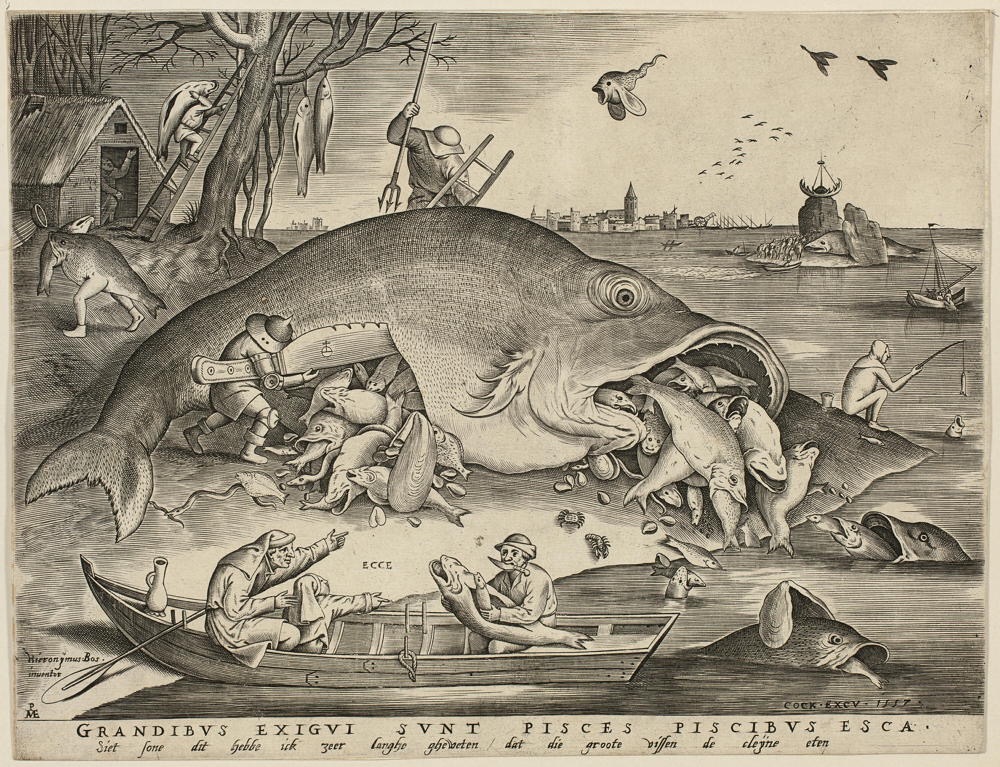

Pieter van der Heyden, after Pieter Bruegel:

Big Fish Eat Little Fish (1557) Published by Hieronymus Cock

ABOUT THIS ARTWORK

This engraving hauntingly illustrates the proverb that the big fish always eats the little fish. Starting with the larger-than-life fish at its center, the image teems with grotesque activity, as bodies spill out of other bodies and hybrid creatures walk and fly about. Pieter Bruegel seems to take a dim view of humanity here, one of disgust at its seemingly endless capacity to cannibalize itself. This is epitomized in the hybrid fish-person at left carrying off its prize, another fish, in its gaping mouth. In the foreground, a man directs a child’s gaze toward the scene, telling him to “behold” (ecce) the proverbial truth on display.

"Those incapable of imagining a coherent BigPicture should never be considered leadership material."

My degree compelled me to enroll in a Systems Thinking class when I went to university. This was considered cutting edge at the time. In it, I was introduced to a few cybernetic precepts and assigned to "design a nuclear-powered electricity generating plant.” I knew nothing about nuclear power or generating electricity, but the instructor showed me how to start with a BigPicture notion of how something like that would have to be configured to work. It would require certain inputs to produce desired outputs, and specific functions would need to occur within the system. The professor demonstrated how to group similar functions into what he referred to as "subsystems." I needed to let go of my natural need to describe details to succeed. I wouldn't need to concern myself with what bolts might hold together a combustion chamber. Those were "mere" details. To arrive at a useful BigPicture, I'd need to presume more than any plant designer needs to define. I was instructed to maintain a useful altitude.

From that perspective, I surprised myself by creating a reasonably practical-seeming high-level portrait of the plant in that exercise. Each subsystem could be further detailed, but the completed design seemed cognitively complete even though it omitted most physical parts. I later learned that Systems Thinking was how executives cope with their otherwise unmanageable number of details. The quality of their involvement depends upon the quality of their internal BigPicture, and every CEO's internal models tend to eventually grow dated. The details never sleep and never stop evolving. When I joined a company after graduation, I was surprised to discover how little the overseeing executives understood about the operations they were supposedly running. They depended upon a descending hierarchy of assistants to cover all the details they would never even attempt to understand. The quality of those communications mattered, though they tended to be flawed. Not every minion could speak the whole truth to power. Not every executive was necessarily receptive to some subordinates contradicting their internal model.

It's a genuine wonder that anything ever gets accomplished. Those operations organized as co-equal communities tend to perform much better, though many examples of dictatorships still abound. I suspect that the lure of control seduces some. Many don't seem to know any better. Curiously, sometimes, success undermines what began as co-equal communication. Personalities influence operations more than the formal process descriptions ever disclose. Put a headstrong person into a system needing careful nurturing, and the system suffers. Listening might prove more important than commanding. It's a constant challenge to balance everyone's internal model with whatever might actually be happening out there.

The degree to which the contributors' internal models agree might be a rough measure of the system's coherence. I do not suggest that a system within which everyone's internal models remain more or less in synch will not experience problems. They're always prey to agreeing upon some incorrect characterization and marching forward as if, but generally, control remains more possible when the BigPicture's widely shared. We've all seen examples of hidden executive agendas, where the CEO's BigPicture is not only not shared, it's considered a state secret. Then, the directions coming down from the top might seem erratic and nonsensical. When working together, the collective construction of the over-riding BigPicture might be the most critical effort the group ever undertakes. It will hold the space for everything else to occur. It might make the motions make sense.

This could all be little more than textbook understanding. In the real world, people tend to get clued in on a need-to-know basis, with some out-of-context somebody determining who really needs to know. Everybody creates their own BigPicture portrait of their circumstances, and almost nobody's a fully qualified nuclear power plant designer. We imagine black boxes performing critical functions, and we also imagine functions not ever actually performed. We inevitably mischaracterize. This is why we try to keep our certainties at bay, for they are often our most volatile opponents. Collective effort too-easily becomes a parody when we feel we cannot disclose our BigPicture. Even when attempting to disclose, 30% might accept the description and about the same reject it, with 40% not paying attention or really caring. Everyone leads a fragmented force. It's even worse when the leader's BigPicture proves to be incoherent. Some leaders never seem to create a BigPicture. They might not care how anything actually occurs. These most often abuse the systems for which they're responsible.

Those incapable of imagining a coherent BigPicture should never be considered leadership material.

©2025 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved