Constulting1

"Clients do not like to be told what to do, no more than any sentient adult does …"

I left The Best Of All Possible Mutual Insurance Companies In The Greater Portland Metropolitan Area (Bar None) after fifteen years of dedicated service to their policy owners, to join a small boutique consulting firm in Silicon Valley. I was unqualified for the position, but didn't know that yet. In that first year, I learned that my new consulting firm sported a phony Sanskrit name which we'd translated as "crossing the great water with balance." Since Silicon Valley was then and probably still is pre-literate, clients there were very attracted to magical-sounding names. We took full advantage of that. A native Sanskrit speaker workshop attendee informed me of the deception during a break. I swallowed hard and carried on. Much of the consulting company's material was of questionable heritage. It started as a genuine survey by qualified questioners, but the distributed materials, I learned during that first year, had been crash-developed over a weekend by a very skilled HR professional who had never actually practiced the profession the material purported to teach. I do not imply that the material was worthless, for it seemed to induce a shift in the manner in which participants thought about project work, which was a subtle, perhaps even unintended consequence, but a nonetheless valuable one. ©2019 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

By the end of that first year, I was the only consultant in the firm that brought in more revenue than I cost the firm in expenses, this no doubt due to the fact that I had negotiated a starting salary about twenty thousand dollars less than I would have made had I stayed at the insurance company. Like all consulting companies, though, this one was about sixty percent cult, and I was convinced that I'd found my tribe. The words and the music didn't always jibe, but I had the satisfaction of feeling that I was making a real difference in the world. I had not agreed to join in the hope of getting rich, and I did not, but after three years, the place fell apart and I, almost the last one standing, inherited the intellectual property. I rewrote the workshop materials over a considerably longer period than a hectic weekend and hung up my own shingle.

Neither a trained instructor nor a certified consultant, I commenced to making up my practice as I went along. I fancied myself a BriefConsultant®, informed by the tenets of the Brief Therapy Movement, though not a trained therapist, either. I learned on the job, following my intuition probably more than I followed my head. Nobody had ever been to a workshop like mine before, or consulted with a consultant like me, either. I insisted that the client decide how much to pay me. I insisted that workshop participants tell me what they wanted to learn, then tried to hold them accountable for pulling that out of their workshop experience, which they almost always did. A few accused me of charlatanism, but I deflected these complaints, offering to refund their money in full if they were dissatisfied with the results. Only one person ever took me up on that offer, and everyone else in that workshop section understood that he was the sort of person who attends workshops looking for ways to blame the facilitator. This sort of experience comes with the territory, but amounts to pocket change.

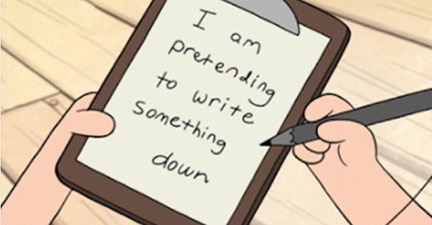

I never knew what I was doing. I could not back up anything I ever did as a consultant with verifiable evidence that I was operating according to any standard or norm. I listened closely and invited my clients into dialogue and we usually managed to create a delightful outcome. I thought of myself as less of a Charlie Tuna consultant, uninterested in imparting good taste and almost obsessed with creating something that tasted good. I had a 'dodge', that essential explanation Damon Runyon's Broadway shysters employed to explain what they did to their mothers. I taught and consulted in the dark art (or murky science) of project management, a sort of magical metaphor in those days. Everyone managed projects and nobody was particularly impressed with their results. The promise of better encouraged invitations. I still didn't get rich, but continued to firmly believe that I was making a difference in the world.

My operation didn't really take off until The Muse joined in. She possessed most of the skills I didn't and we made a fantastic pair. She, for instance, schmoozed well while I was a more facile inventor. She marketed, I wrote. We claimed that we never did the same thing once and promoted our consultancy as "expert at not being the expert." We still didn't know, never knew, how to solve any client's complaint, but we understood that knowing might well prove more of an encumbrance to discovering some delightful result. The Muse understood what Balanced Scorecard meant. I never cared to learn because I didn't want to know. Clients do not like to be told what to do, no more than any sentient adult does, and to our minds, there was no better way to prove the old adages about consultants than by edict, especially if the client invited us to command them. I figured that the invitation to just show them how to do something right represented an abrogation of their own authority. I suspect that nobody knows at the beginning how to resolve any complaint, but only some consultants have the cahones to admit their utter ignorance and only some clients understand that they're about as skilled at self-diagnosis and prescription as any run-of-the-mill anti-vaxer.

My tenacious not-knowing sometimes left me feeling wholly inadequate. Though my experience might have clearly demonstrated that knowing, pre-knowing, encumbered resolution, I still sometimes carried a considerable imposter burden. No, I'd never personally managed a multi-billion dollar telecommunications project, but the ones who have do not seem terribly satisfied with their results. I could wonder why that might be. I've still never seen a technology problem that ended up being mostly about the technology. Likewise, I've never seen a project management problem that could be fixed by a more forceful or determined application of project management theory or accepted practice. The best a client could achieve by slavishly implementing so-called Best Practices might be competitive parity. Who would leave any garage to toodle around achieving that?