Coping

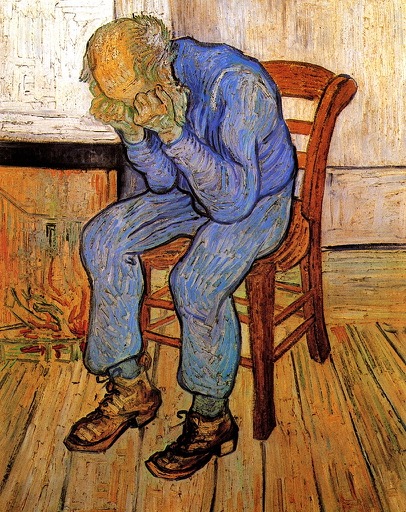

Vincent Van Gogh: Old Man in Sorrow. On the Threshold of Eternity, 1890

"We do just what we do, which might be the very wisest response any clueless anyone could ever muster."

I consider coping to be more emotional than any learned skill, and resilience, more a matter of personal pattern. Lose someone and one does what they do, and might not even notice what they're doing then. Coping amounts to one of those responses that don't necessarily register as a response. Given a significant-enough loss and a sort of auto-pilot seems to kick in without cluing in the pilot. I remember when my sister Susan died in a car accident, my youngest sister flew in for the services and I spent a long day tour-guiding her around the town I lived in. Only later did the excursion seem in any way questionable to me and she just numbly followed along. I was numbly leading, coping as I now recognize that I cope. ©2020 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

In the Midwest where The Muse grew up, a death prompts all the women to start cooking, usually scalloped potatoes. When The Muse's father passed, a long line of neighbors delivered steaming baking dishes filled with what they locally refer to as death food. Enough to feed the town eventually arrived, and since the whole town attended the service, nobody left hungry. Our GrandOtter last weekend lost a friend in a hit-and-run, and I watched her go catatonic after receiving the news. Supper suddenly seemed superficial. We each picked at our plates. Yesterday, I whipped up a batch of her favorite, Mac and Cheese, and she dug right in. Comfort food, they call it, and it did seem to ease the tension in the place.

The GrandOtter and I chatted about her mourning ritual, though she admitted to not really having one. She's a part of the generation who's lost more of its members than any since the development of vaccines, so she's lost what I refer to as 'more than her share,' including a step-brother. I reported that in some cultures, the response to death seems almost automated. The women don black dresses and unashamedly weep while the men mumble in small circles while smoking and sipping the local spirit. In our culture, no such pre-programmed response lurks, so it's each to their own chosen method, though there seems to be little choosing involved in the selection. As we mourned the lack of a standard ritual, The GrandOtter was searching back through her voluminous photo archive separating photos of her so recently departed friend. I suspected that we were both witnessing her coping strategy in action.

Over the Mac and Cheese supper, I mentioned my observation. The Otter later reported that my comment amounted to her epiphany for that day, which just happened to be Epiphany. My comment was one of those SmallThings I keep yammering on about. SmallThings with huge significance. Back when I was a professional, I'd often rail about the utter insufficiency of every training I'd ever been subjected to. I wanted a class that would impart the missing link, as I perceived it, in every professional activity: What Do You Do When You Don't Know What To Do. I later came to understand that just catching myself in a Don't Know What To Do state amounted to perhaps an even more significant barrier to full professional competence, but one perhaps addressed by merely becoming a bit more sensitive to my own internal state. If I could catch myself not knowing what to do—a huge order given my professional-grade denial skills—then I could simply watch what I was doing and learn, at least for for that instance, exactly what I do when I don't know what to do, then I could simply choose to do something else if that coping ritual wasn't satisfying me. Easier said than done.

We each cope how we cope, and part of coping seems to be a certain obliviousness about what we're doing then. At that point, a small observation dropped into that void might help level the experience a little bit. We do what we do, but often without really recognizing that we're doing much of anything. Absent a deeply ingrained ritual, we might never notice how we cope. In my career as a consultant, my practice usually relied upon Virginia Satir's comment that the problem isn't the problem, how we're coping with the problem is the problem. I'd more closely observe what people were doing rather than seek the source of a reported problem. Their coping almost always served to amplify the underlying problem's effects and few would recognize this cause without an uninvolved observer commenting. At least half of every complaint could usually be resolved by injecting just an ounce of awareness into the unacknowledged coping ritual. Dysfunctional coping struggles to sustain itself in light of such self-awareness.

The Otter commented that she felt as though she'd been in mourning for years, and I didn't doubt her admission. She had been under the conviction that she didn't know how to cope and so could not properly dispatch her grief. Grief was never intended to become a lifestyle, but The Muse sagely reflected that it might just be that nobody ever successfully dispatches any loss, but that their grieving ritual tends to attenuate its more pointy parts over time. Now that The Otter understands that she has always had a coping ritual, albeit previously unregistered, we'll see where her grieving might take her next. None of us might really know what to do when some shock steals away our self-confidence, but most of us manage to do something, and that something holds significant information if only we could decode it. We do just what we do, which might be the very wisest response any clueless anyone could ever muster.