Fairing

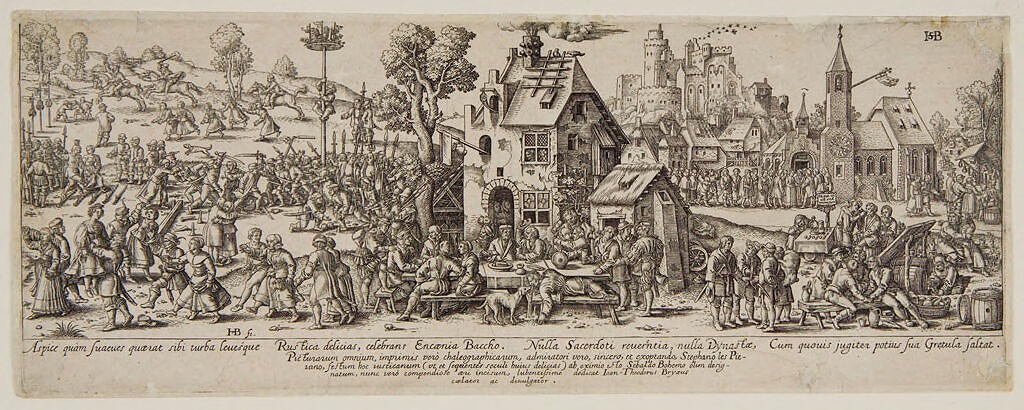

Johann Theodor de Bry:

Little Village Fair (16th-17th century)

"The less than generous sociologist in me steadfastly refuses to see the resemblance."

Last week was Fair Week in the Valley They Liked So Well They Named It Twice. The Southeastern Washington Fair and Rodeo has been an annual event since the eighteen-sixties. It was a highlight of every one of my summers growing up, occurring just when the new school year was starting. We'd begin the school year the Wednesday before Labor Day, then take the following Friday and Monday off. No better way to start a new school year than with a four-day weekend! That Friday would be Kids' Day, and we would flood the fairgrounds to ride the rides, eat the food, and win goldfish that were inconvenient to transport home. We'd wear Rosellini for Governor buttons and dutifully tromp through animal barns and pavilion displays. In its day, the Fair seemed a pretty perfect portrait of our small city's personality, from the Saturday morning parade to the parimutuel horse racing.

The Fair seems less grand now. Of course, I'm larger than I was, so everything should seem relatively smaller, but more than that, the celebration seems greatly diminished. For instance, The Saturday Morning Pancake Breakfast no longer exists. The horse racing left, outlawed, I guess, by state regulations. I could care less about the rodeo, but even that might have melted into glitz, more hat and much less horseflesh. Even the farm equipment, which I long suspected represented the real reason the fair was held, has become impossible to relate to, offering twenty-foot-tall tractors and combines costing several times the price of a new Maserati. The legions of harvest workers who used to flood the fair are also no longer there, replaced by machinery and long-closed-down canneries. This small city suffers from an identity crisis throughout every fair season.

Even The Pavillion, the enormous round barn that houses the 4-H exhibits and exhibitor booths, seems to be a pale shadow from earlier days. Once filled with a warren of booths finished in indoor paneling, a reliable collection of exhibitors returned yearly. A remodel opened up what was once undoubtedly a fire hazard and removed the familiar sights and smells, leaving a multipurpose room in its stead. Booths still stand, but they're curtained affairs, too regular and ordered to be very interesting. The usual candy and pepperoni vendors sit alongside the gutter and solar suppliers. About a quarter of the booths belong to various religious groups, each seeming more fundamentalist than the next, some sporting posters of fetuses masquerading as humans—a spattering of political candidates round out the census. People shuffle through the aisles as if entranced. It doesn't seem the least bit obvious what attracts anyone inside, for it's stuffy and way too hot there. It might be tradition that brings them in, the sense that they might brush up against what no longer exists. That's what brings me inside.

I was working our candidate's booth, a banner, repurposed yard signs, and a table covered with literature. Working a booth provides the best perspective, much better than joining the procession through the place. I confided to our candidate that I could hardly avoid becoming a critical sociologist sitting there watching people shuffling by. Family groups seem to assume pecking order positions, some with dad leading and others with mom. Some multigenerational groups move past like curious raiding parties with grandma in her motorized wheelchair, and each generation arrayed around from there, each displaying the complete history of their dietary choices. Youth seems appropriately alarming, pierced, and tattooed in ways seemingly intended to offend and disturb. Many 'get-ups' pass by, outfits we wonder how they ever got past mom's radar to leave the house. Years ago, at the New Mexico State Fair, I was in a contest to identify the carney with the fewest teeth and the most disturbing example of jail bait. Something about a fair encourages fourteen-year-olds to dress up like (insert whatever inappropriate word you feel moved to insert here.)

As appalled as I always feel when watching the pavilion parade, I feel moved to acknowledge that it accurately represents this small city's present inhabitants. The finest citizens pass through along with the lowliest, and each portrays who we are, though we might not immediately recognize ourselves. We find few opportunities to mingle these days. We're notoriously clannish now and rarely stray across demographic boundaries, except when attending the fair. The parade of people trudging through the pavilion seems projected in a funhouse mirror, but they're me; they're us. The less-than-generous sociologist in me steadfastly refuses to see the resemblance, but I know I don't cast quite the same trim shadow I did in my youth. My footprints are several sizes different than they were then, and I cannot reasonably divorce myself from this reality. It seems unfair, but the fair has always been there to remind me who I might actually be. Gratefully, we break down the display today and store it away until this time next year when, if we survive, we'll again embody what we so rarely see and struggle to acknowledge. I'm trudging toward becoming the carney with the fewest teeth, though I'm long past ever being mistaken for jail bait again.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved