Jobsite

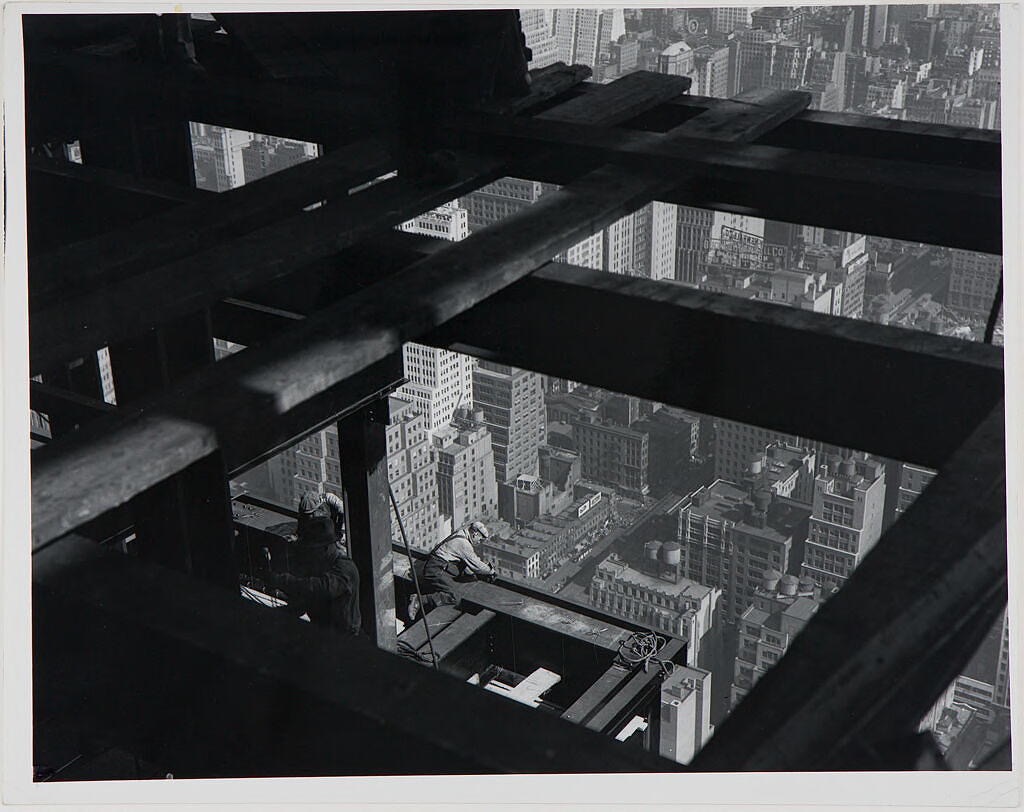

Lewis Wickes Hine: Construction--Empire State Building, (1930-1931, printed later)

" … we will sorely miss this sacred inconvenience."

A home becomes a jobsite quickly, without very much fanfare. One minute, I was breakfasting on my front porch, and the next, or at most the moment after, that porch was being roughly disassembled. I double-locked the front door to prevent anyone, me included, from inadvertently stepping out into air improved only by naked joists. The idea that such a thing could happen haunted me every time I passed by that door through the first weeks. The view out the bottom-of-the-stairs window became a peek into the progress of the deconstruction and the following rebuilding. I stepped around construction materials to set sprinklers and tried to remember to move the vehicles before the work crew blocked the driveway every morning. The whole rhythm of my life changed.

A work crew seems the rough equivalent of a haunting. They're respectful and stay in their space, but they can't help but peek through windows as they pass. They upset the normal rhythm of the place. The neighbor complained that she could hear their radio while on her Zoom® calls, so I reluctantly asked them to keep the volume down. I rather enjoyed their injecting their genre into my audio background; accordions are so rarely employed in North American popular music. The sounds of hammers and saws, even jackhammers, jiggled and jarred the place. I sometimes couldn’t hear above the din. I've sometimes felt the need to flee, to become a virtual refugee from the chaos and noise.

I set up a Peanut Gallery beneath the front yard hemlock tree. From there, I could see pretty much everything going on. I'd occasionally wander over for closer looks, but the language barrier between me and the crew served to keep me more separate than I preferred. I like to stay on top of whatever's happening on my property, but I found that I needed to back off and trust the people I'd hired to perform the work. I was not their supervisor, even if I was their employer. I felt more dependent upon them than I imagined them dependent upon me. Yes, they were working to satisfy me, but I was so unsophisticated as to be unable to determine the quality of their contributions. I judged the quality of their efforts by how cheerful they seemed when engaging together. This genuinely cheerful crew was constantly joking and singing, joyful in their efforts. I considered this to be a great omen.

I came to rely upon their arrival each morning. I'd have watered the adjacent lawns so as not to bother them and their work. I would have moved vehicles to park them on the street, carefully leaving ample room for their trucks and trailers to park closest. I was out the door and in conversation the moment Pablo, the concrete contractor, arrived, available to answer any questions and to make a few queries of my own. I kept a close-ish watch over whatever was happening. I understood that we were dealing with forever and not merely superficial changes. The concrete they poured would survive for generations. This work will stand as perhaps the last testament to our existence a hundred years and more from now. A few weeks' inconvenience might be a modest price to pay for such immortality.

I can definitively say that I never feel more alive and vital than when my home becomes a Jobsite. The intrusion lends me purpose beyond my regular hygiene efforts. Even the inconveniences satisfy me, convincing me that I'm contributing something more than simply taking up space. I'm a part of the effort to create space that didn't exist before. I'm part of my own future for the few weeks the Jobsite persists. I abhor the dust, the noise, and the waste, as ancient beams and braces get switched out for more modern components that are not half as strong as what they replace. I didn't want to modernize, but to historicize, to undo some unwise improvements done by prior owners to restore the home to closer to what it originally was. Backing back into a future lost in the century since original construction. If that transition requires that I live in a Jobsite for a few weeks, so be it. It will be quiet for decades after this din subsides, and we will sorely miss this sacred inconvenience.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved