NewWorld

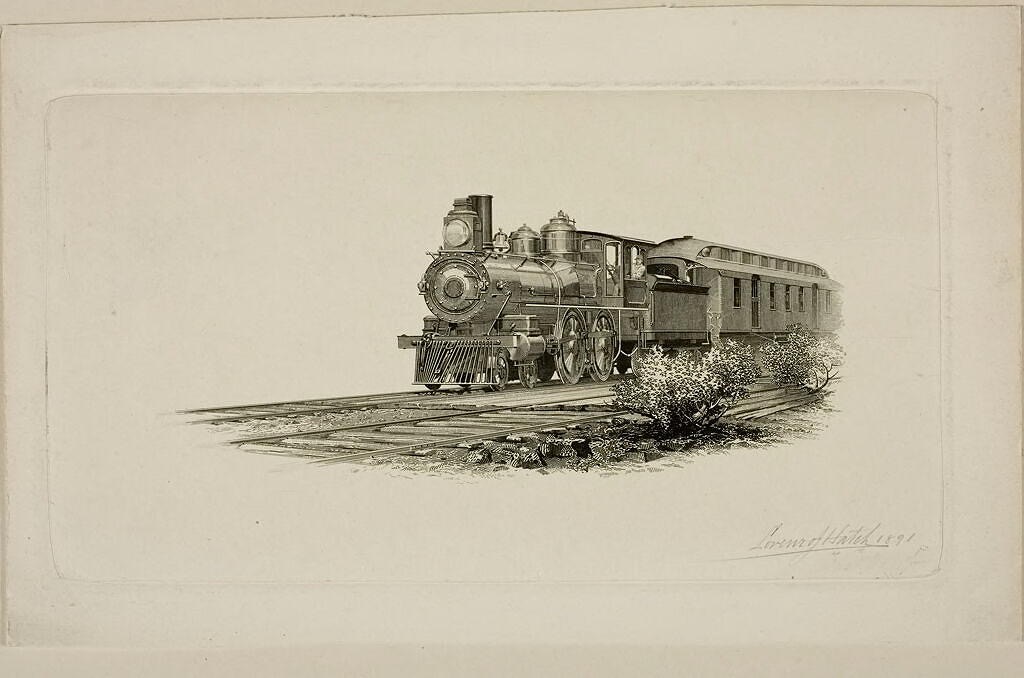

Lorenzo James Hatch: Locomotive (19th-20th century)

" … that success would ultimately cost him plenty."

As in every previous generation, arrival in a NewWorld involved stepping backward in time. The Schmaltzes and Welks had left behind their mature development in Ukraine, trading generations of successful adaptation for generations of even more of the same, starting from about where their displaced great-grandparents had begun when arriving on the undeveloped Steppe from Alsace a century before. Just before the turn of The American Century, North Dakota was closer to where it had been a century earlier than where it would end up a century later. The railroad had yet to cross half the state. Indeed, they arrived just as The Dakota Territory was admitted to the union as North and South Dakota. There were no paved roads in either state then. Settlers were still building sod houses, there being little available lumber or stone to create anything more substantial.

A government survey completed in the 1860s, when The Dakota Territory was first established, concluded that the area might productively host a dozen ranches, given the extreme weather and short growing season, and that most of those ranches might raise cattle rather than crops. This conclusion contradicted the railroads' intentions, for they needed towns about every ten miles to at least host a water tower for their steam engines. Further, those railroads would need labor through the winters to keep their lines open following blizzards. Those railroads sent agents to Europe, probably even Ukraine, touting the free land and unlimited opportunity their territory promised the enterprising emigrant. If my forebears were anything, they were enterprising. The Germans came by the thousands, by the tens of thousands, creating whole towns of German speakers reminiscent of where they'd come.

The Muse's forebears had come from Czechoslovakia two decades earlier and settled in what would become Southwestern Minnesota just in time for one of those occasional killing blizzards. Her Great-Grandfather was out plowing with oxen when a pleasant day suddenly turned freezing. A white wall descended over his place as he headed for his barn. He somehow made it to his barn but was stranded there for three days, his young wife and their newborn nearby in their sod house. He couldn't hope to find the place in the whiteout conditions. After three days, the wind and snow abated, and he crawled up and out of his barn to find a featureless world. The snow had drifted to cover every building. He found a sooty ring emitting smoke from beneath the snow covering and, digging down, found his sod home, wife, and child waiting for him. That was his introduction to the NewWorld.

The Schmaltzes and Welks settled around Devil's Lake, North Dakota, founding Strasburg and Rugby with other emigrants. They named Strasburg after one of the colonies they'd left in Ukraine, which in turn had been named after a town back in their native Alsace. The Old World informed their NewWorld places. The emigrants took laboring jobs laying track and shoveling out snowbound trains, and sure enough, a small town was founded just about every ten miles across the plains. Amy's forebears worked twelve-hour shifts, living in mobile dormitories on wheels pulled behind the trains. They were farmers in name only at first. The railroads provided the seed money for their investments in farms and equipment.

Almost every farm founded during that time would fail. They didn't fail at first, but eventually, the prescience of that territorial survey came home to roost. The farms still producing are conglomerates, combinations of many original claims either sold or leased out to ever larger operators who turn their profits leveraged upon colossal scale and, as they say there, farming the government. The dust bowl would visit a few short decades after my forebears arrived. They would be cheated by the Cargills and Archer Daniels Midlands, and the railroads would sometimes be lifesavers and, other times, harsh overseers. They'd join the Grange and, later, the Farm Bureau and build an industry, another breadbasket of the world. Many of that first generation would never speak anything but German.

My Great-Grandfather, though, only paused in North Dakota. He would head to Oregon, to another town where everyone spoke German, where he would become one of the wealthiest men in town, though that success would ultimately cost him plenty.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved