North

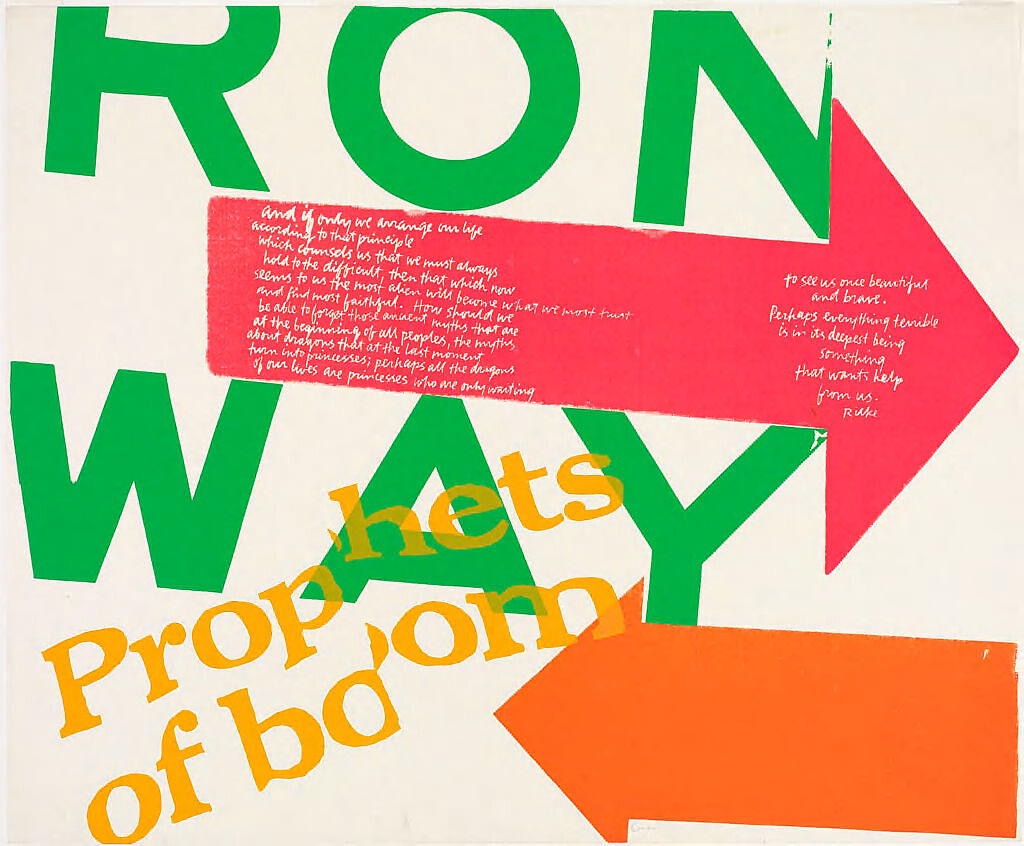

Corita Kent (Sister Mary Corita): right (1967)

Inscriptions and Marks — Signed: l.r.: Corita

(not assigned): Printed text reads: [W]RON[G] WAY / Prophets of boom / and if only we arrange our life according to that principle which counsels us that we must always hold to the difficult, then that which now seems to us the most alien will become what we most trust and find most faithful. How should we be able to forget those ancient myths that are at the beginning of all peoples, the myths about dragons that at the last moment turn into princesses; perhaps all the dragons of our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us once beautiful and brave. Perhaps everything terrible is in its deepest being something that wants help from us. Rilke

" … With our attention finally properly focused …"

To move to Washington, DC, is to confront racism face to face. In many places, the racism seems securely hidden to the point that you'd swear it doesn't exist there, except, perhaps, in that one isolated quarter where African-Americans traditionally settled. In Portland, Oregon, where I spent twenty-nine years of my adult life, the "black" neighborhoods had been developed using an overt discrimination called "redlining." Banks would only loan mortgage money to African Americans in certain areas. When I-5 was created, it was built right through the middle of that designated area, further fragmenting and isolating the neighborhoods there. This practice was hardly unique to Portland, though. Seattle was no better and might well have been worse. The Bay Area in California designated Oakland as their minority area and the East Bay. East Palo Alto was, for years, the South Bay's designated ghetto.

When shopping for neighborhoods, our realtor advised me to avoid certain areas. I steered right into them only to find I might have been well-advised. Most of Washington is African-American. The distinction between black and white might be less engrained there than anywhere in this nation, yet it still exists. The differences don't only lie in the wealth of a neighborhood. North of The Mall, along the eastern edge of Rock Creek Park, lies an area referred to as The Gold Coast, an affluent, traditionally African-American neighborhood. The houses are grand, and the streets broad and tidy. Off to the periphery, signs of blight encroach as one enters Florida Avenue and Petworth North of Columbia Heights. Closer to town, down through Dupont Circle, the neighborhoods seemed thoroughly gentrified by the time we arrived, and those neighborhoods were distinctly urban, largely multi-family, often high-rise, with single-family houses rare and expensive.

Everything to the Northern edge of Rock Creek Park seemed too exclusive or blighted to be very interesting to us. We confronted our identity cowering there, wondering where it might find a place congruent with who we'd come to know ourselves to be. We were capable of that kind of change but inexperienced. We were not high-rise people, nor did we seem to belong in a genuine "hood." The houses seemed too tightly spaced together there, such that neighbors couldn't help but constantly be in each others' business. Parking seemed exclusively on the street. Yards also seemed tiny and were often unkempt. It's tough to tend a tiny patch of anything shaded behind a necessarily tall security fence. The commercial strips seemed almost derelict and scary. I honestly couldn't see myself feeling secure walking to any of those corner stores. I wouldn't want The Muse walking up from the Metro after dark, either. It seemed every park featured a clutch of young black men, often hovering around the basketball court. They'd trash-talk me as I crept by, probably as uncertain of my intentions as I was of theirs. I felt like I was on display on alien ground.

West from the midline Rock Creek Park, the neighborhoods were uniformly upscale. Georgetown and Friendship Heights, Chevy Chase, and Bethesda seemed beyond our means. We felt as though we'd entered some race about two decades behind. Everyone else seemed to have entered when real estate had been affordable. Every rent seemed unreasonable. Our house search often felt like a crisis as we continually confronted a reality in which we felt utterly powerless to compete. Further North, we found decidedly suburban ground. We knew we weren't urbanites but were just as sure we'd make lousy suburbanites, too, so we searched for a neighborhood that might not even exist. We persisted.

We looked at plenty of places, often convincing ourselves before we went that this latest place would probably be different. Few were. Through disappointing iteration, though, we painfully slowly found ourselves searching through an ever narrower space. An old acquaintance connected us with his sibling, who lived in what might prove to be a proper neighborhood. We visited and were sold. We found ourselves repeatedly drawn to that corner of the city, the Northeast, to Takoma Park. Affectionately referred to as The People's Republic of Takoma Park, it was perhaps the quirkiest section of the city. Decades ago, attracted by the resident Adventists' health food stores, gays and hippies started buying real estate there, painting their Victorians garish colors, and eventually chasing out the Adventists to a more northern and suburban suburb. It was just about the perfect commute, forty minutes, give or take, and featured a tiny little downtown with a proper selection of shops. It didn't feel like a big city. Once we'd found that neighborhood, it merely became a matter of finding a place to rent there. With our attention finally properly focused, we found renewed faith that our new home place might find us.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved