OddEnds

George W. Boynton, Engraver

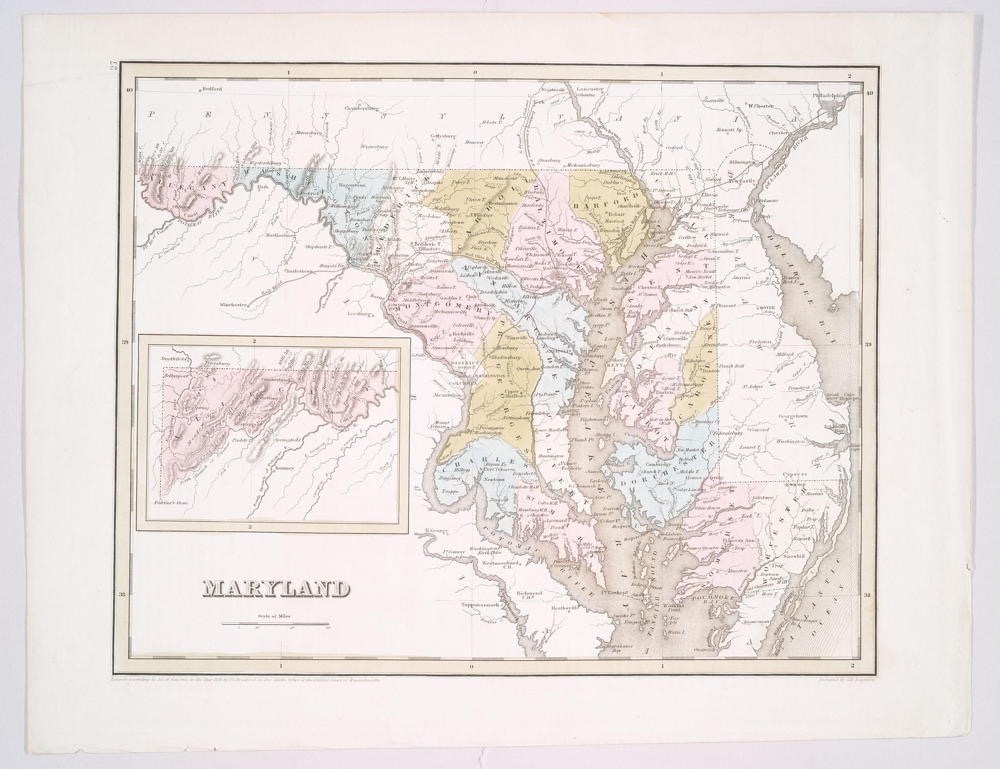

T. G. Bradford, Publisher: Maryland (1838)

"The story could have been irretrievably lost in any generation."

Over half of the people coming to the British North American Colonies before the Revolution came as indentures. In 1674, one of my ninth great-grandfathers appeared in court in Maryland. A ship's captain, Thomas Jones, brought my forebear, his servant Edward "Teage," before the court, asking the judge to assess his age. The judge decided he was fourteen. The following year, Jones returned to court to claim a "headright" of land granted to him for transporting Edward Teage and three others to Maryland. A headright claim could grant land to anyone transporting people to the Maryland colony. Typically, those transported then worked as servants to the transporter for some period of years; after, if they survived, they would be free to do whatever they pleased. Fewer than half survived their indenture. Teage survived.

In 1695, Teague was back in court, claiming the right to 300 acres of land. This might have been part of Jones' original headright claim since part of this property was named Tegg's Delight, and, indeed, records suggest that "Teague" might have been living on that land before it was granted to him. Teague's daughter Catherine, born at Tegg's Delight in 1690, later married a wealthy local planter named Mark Whitaker. Whitaker graduated from Emmanual College, Cambridge University, in 1697. By 1702, he appeared on the Spesutia Hundred tax rolls. Whitaker and Teague, my eighth great-grandparents, were married in 1705 when he was twenty-six and she was fourteen, though records show that their daughter, Elizabeth Whitaker, was born the year before, in 1704. Elizabeth Whitaker-Swift became our Flower Swift's grandmother, wife to constable Flower Swift, who apparently died at sea in 1742. They were my seventh great-grands.

Teague died on March 9, 1697, at Tegg's Delight. He drowned in a creek while fishing. His body was never recovered. His widow remarried to the executor of her first husband's estate, and I can imagine some pressure to marry off the daughters. However, thirteen seems particularly young, especially considering the legal age of maturity in Colonial Maryland was twenty-four. Every family's history includes tragedies. Teague's untimely death reverberated down through subsequent generations. His original homestead is now a Girl Scout Camp, Camp Conowingo. The original chimney and portions of the homestead still stand where he set the stone nearly 350 years ago. Teague's death was shocking, though hardly unusual. Flower Swift senior's departure was likewise unscheduled and unsettled the survivors.

Letters written by later forebears invariably ended, "If I live," reflecting the everyday uncertainty they'd been reared to accept. They went forth anyway as if they had any viable alternative. Teague's birthplace and, indeed, his parentage remain unknown. For legal purposes, his birthplace was tagged as Bristol, England, but that was a convention. The ship's captain, Jones, who transported him to Maryland, sailed out of Bristol, and it was the custom to ascribe a point of departure as the place of origin. Everyone's history eventually fades into such obscurities. I realize it's rare for someone to uncover names and dates associated with any ninth great-grandparent. Given the OddEnds so many of my predecessors ultimately came to, I feel incredibly fortunate. The story could have been irretrievably lost in any generation. Even our histories themselves remain forever subject to OddEnds.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved