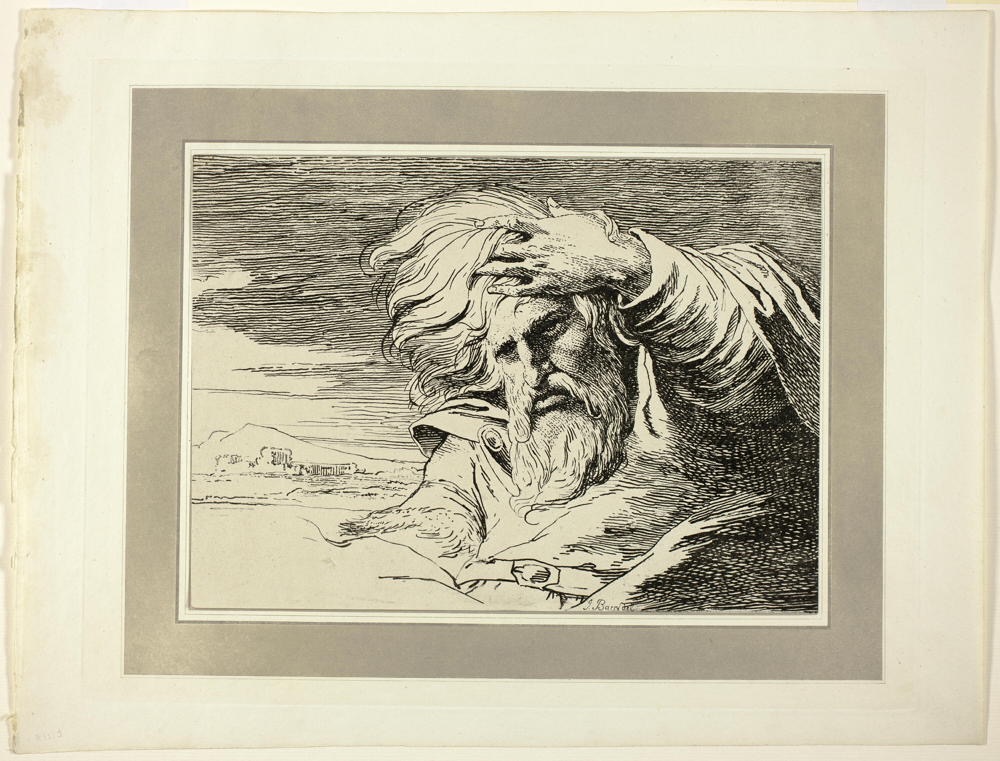

Patriarch

James Barry: Eastern Patriarch (1803)

"sate in stocks for railing."

Patriarchy can prove to be slippery to determine. In some ways, each generation produces a patriarch, though some generations produce especially noteworthy ones. Those who serve as the center point of a grand convergence or the point of exceptional dispersal most often earn the label. In practice, assigning this title must surely prove arbitrary, with little besides opportunity or convenience deciding. In the Kenaston clan, I choose to name John Keniston, my 8th great-grandfather, born in 1615 in Manchester, England. (Spellings were fluid then; Keniston remained with an 'i' until around 1700 when the 'a' replaced it.) He arrived in Dover, Massachusetts Bay Colony, in 1623 at the age of eight. His parents, Henry and Elizabeth Leeze, and his sister, Mary, and brother, James, died of "The Sickness" shortly after their ship, Margaret and John, arrived.

At age thirty, in 1645, he married Agnes, daughter of The Reverend John Moody, and settled into the fishing village of Strawberry Banke, now known as Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Pilgrims kept terrific records, so I can follow John's life through his recorded court appearances, taxes, and land grants. He was fined in 1667 for excessive drinking, and, in 1670, he was presented at court for fighting with Mr. Henry Shurband. ( A year later, Mr. Shurband and his wife were presented in court for "disorderly living and fighting.”) Whatever image we carry about the presumed piety of Pilgrims, their records show clear evidence that they were human. Colonists kept slaves, both Indian and African, and, indeed, traded in slaves with both Africa and the West Indies.

In 1671, they lost a son, Alexander, who drowned while attempting to cross a river on horseback. The Kenistons lived on the northern edge of the colony, so they were very exposed to the threat of Indian raids. In April 1677, during the so-called King Phillips War, Our Patriarch was killed by three natives named Simon, Andrew, and Peter. His family escaped unharmed, though they lost their home, which was burned in the raid. John was fifty-nine years old when he died, but his presence on this continent contributed to setting up the conditions that would eventually bring my second great-grandparents together in 1863 and set them on their way West.

The Kenistons would remain Yankees until sometime after 1818, when my 4th Greats moved to Ohio, then the 3rds to Illinois, and later to Oregon. While in New England, they lived along the frontier, land frequently harassed by French and Indians until The Revolution. They were certainly no strangers to danger. I can't say how many others find ancestors who were victims of native uprisings. I've found two so far. I don't think there are any more in my story, but the settlers were never merely innocent victims. The conditions under which they lived guaranteed confrontations. Tensions were just a part of the context within which they lived.

After John was killed, his widow remarried to a man named Henry Magoon. Before then, in 1677, Agnes had been sentenced to "sate in stocks for railing." Whatever in the heck "railing" was. I find deep satisfaction imagining my 8th great-grandparents sideways to Pilgrim justice.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved