SchlockWare

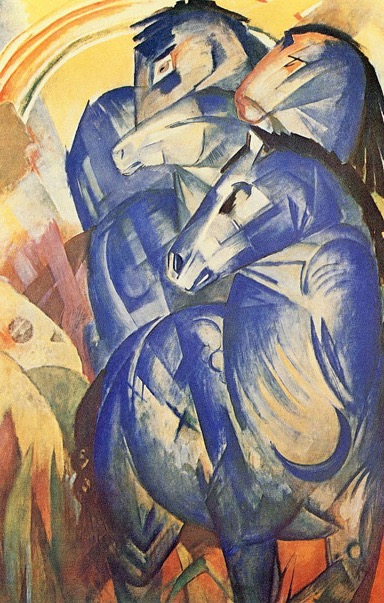

Franz Marc: The Tower of Blue Horses (1913, missing since 1945)

"Our virtual existence seems remarkably similar to our actual one."

Our Damned Pandemic has driven those of us not formerly living virtual lives into ever deeper virtuality, a rough mock-up analogue of what previously passed for reality. I meet weekly with a group of friends, few of which I've met face-to-face, employing Zoom, currently the most popular interface. I convene the gathering, but understand only the barest trace of how to operate it. I hunt and peck and generally succeed, learning a little more about it each week. I will never flawlessly invoke the screen share feature, probably because it was not designed for seamless invocation. I apologize in advance, then clumsily manage to share my screen after a couple of stumbles in between. We're all forgiving, for none of us have mastered the application, just like every piece of SchlockWare we've grown to rely upon. Not even superuser status would protect us from collectively stumbling when employing it, for I doubt that even its designers have fully mastered it, in the unlikely event that designers were even involved creating it. ©2020 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

Each 'app' seems to have outgrown its founding charter, intended for one purpose then serially upgraded to cover functions never imagined in its initial instantiation. Each evolved to become something it really isn't. A video meeting application just had to add at least a half dozen additional features only distantly related to its original purpose. Chatting, voting, avataring, some even provide the ability to overlay a silly mustache or even a pirate eye patch over a user's video image. Ultimately, the application becomes essentially unusable for the purpose originally intended, though dedicated users will continue to increasingly rely upon it in lieu of struggling to learn a completely new application. Features casually added might get emulated in other apps, as each attempts to corner some market by improving their apparent universality. What might have started as a spreadsheet morphs into a clunky graphics package, losing usability while ever increasing what they call 'functionality,' one of those terms which obviously mean its opposite.

Word, which started as a straightforwardly simple word processing application, quickly became its own antithesis as it attempted to satisfy every possible expectation anyone might bring to it. Writers fled as they realized that it wanted them to become like pool typists, interested in formats and presets, rather than in capturing words. Those who could figure out how to use it lost their spontaneity, perhaps the sole essential quality real writers must possess. Many, like me, fled to the simplest possible text editors, copying and pasting into formatting applications after creating, to facilitate printing and publication. These little text apps fell along the wayside over the years, leaving me (and probably many others) with entire catalogues unreadable by more modern applications and therefore lost to the ages. Whatever starts small and focused either grows bloated and unusable or gets left behind. I entrust my work to applications which I know for certain won't outlive me. There seem to be no alternatives.

I received a survey from the creators of the application I use for final formatting, Scrivener, a bloated and essentially unusable whale of a system. I could not answer most of the survey's questions because I had been unaware of the existence of most of the features it mentioned. I plead guilty to the crime of not having sat through the many hours of video instruction available to every user, for what little I'd reviewed seemed irrelevant for what I'd intended to use the damned thing to accomplish. I just wanted to accumulate my writings into compiled manuscript form, a feat I'd heard it was capable of performing. I spend more time trying to accomplish the simplest of chores, as if I was tightening screws using chopsticks, but so it always seems to go. I told them that I wished their application was easier to use, but I suppose that if it were that simple, it might well prove useless to all of its users who use it for writing. (It was clear to me that the marketers believed that they were selling and supporting a writing application, a use for which I've found it utterly useless.)

Our brains work in similarly mysterious ways. Scientists are forever scanning them to determine what chunk processes which sensations, often, it seems, with decidedly mixed results, for brains seem to operate entirely unlike modular systems. They seem to share resources between various parts, and employ different pieces to process the same thing at different times. I should not be surprised that SchlockWare seems to evolve into this same pattern. Facebook lays bare the notion that the same function operates similarly everywhere within the system. Calling the result a system sort of stretches the notion of what constitutes a system. These things which are not things at all rarely feature internal consistency, except apparently accidentally. If there ever was an architect, she left to spend more time with her family shortly after the IPO. Those left behind have been adding features guided by the marketers, who insist upon ever increasing sizzle to fuel further dominion. Our virtual existence seems remarkably similar to our actual one.