Shoestrings

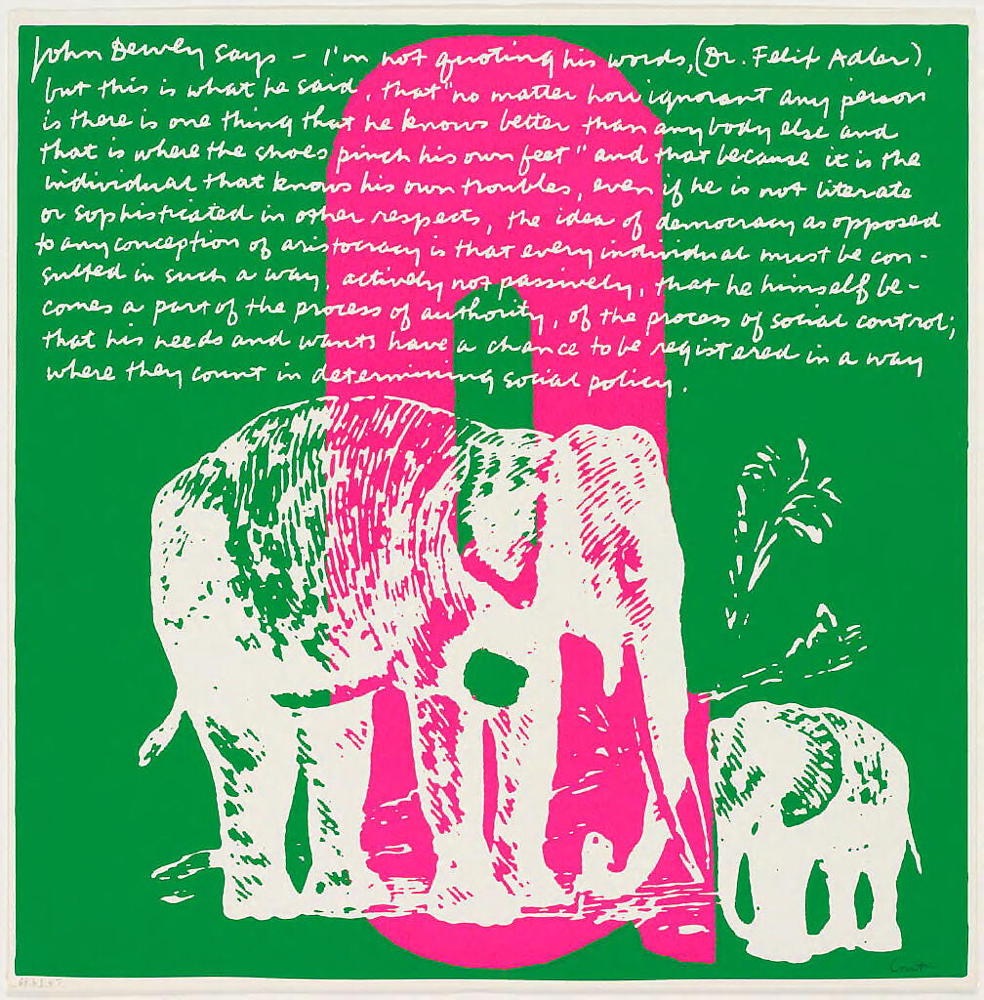

Corita Kent (Sister Mary Corita): elephant's q (1968)

Inscriptions and Marks

Signed: l.r.: Corita

(not assigned): Printed text reads: Q / John Dewey says-I'm not quoting his words, (Dr. Felix Adler), but this is what he said, that "no matter how ignorant any person is there is one thing that he knows better than anybody else and that is where the shoes pinch his own feet " and that because it is the individual that knows his own troubles, even if he is not literate or sophisticated in other respects, the idea of democracy as opposed to any conception of aristocracy is that every individual must be consulted in such a way, actively not passively, that he himself becomes part of the process of authority, of the process of social control; that his needs and wants have a chance to be registered in a way where they count in determining social policy.

inscription: l.l.: 68-69-47

" … undifferentiated others certainly originally came from one."

My parents' birth families seemed to the childhood me to be filled with contradictions. There appeared to be a profusion of odd relations: second and third cousins, step- and half-siblings, what my mom referred to as "Shoestring" relatives. Some were actually related by blood or marriage, while others were adopted, the sort of people one might choose, which, of course, one can never do with any blood relative. Most lived far away. We might have seen them once in all my growing-up years, through town for a reunion or funeral, and never to return. Most had legends associated with them. My mom could recite the stories as if she'd written them, though I suppose her mother taught them before she realized she was teaching her anything. Our Shoestrings complete already complicated enough family portraits.

When The Muse and I were Exiled, we could have sworn that we didn't personally know anybody in the entire region into which we were cast. We were wrong. It didn't take long before a few Shoestrings began appearing as if out of the woodwork. A high school classmate here, a sister's childhood friend there. One after another, Shoestrings began appearing. We were Exiled in an era featuring degrees of separation, the gospel of which insists that no more than six connections separate everyone. We didn't directly know our eventual Shoestrings. We came to know many through somebody we'd already known or someone who knew somebody who knew somebody who did. Word got out, and we began receiving invitations. "I have an old college chum who works in real estate back there. Here's her contact info." "My sister lives in that town where you're interested in settling down. She can probably help you find a place." In short order, a network emerged.

I've long been envious of those who never left their hometown, for they hold a generational understanding of their surroundings. We were essentially blind. For most intents, we were devoid of any history in DC. We could say we knew nobody, but that declaration had nothing to say about who we'd come to know, and we'd come to know many. People were even friendly, volunteering to help the new kids even if they hadn't yet moved in down the block. We received recommendations, which I duly checked out, only to learn that Shoestrings often hold really different tastes for what might constitute decent. I was grateful, though, for every lead and each connection because my only alternative seemed to have been random selection, and such evolution only works on time scales much broader than the few short weeks our temporary housing would tolerate our presence. I suspect that those who never left home might find reason to be jealous of my less permanent connections, too.

We didn't stay in touch with everyone we connected with. That's one of the curiosities of Shoestring relations. They come into focus and then return to blur. They occur seemingly and almost exclusively Just In Time. Before wouldn't have mattered any more than after could have. For the moments we connected, we were both gifted. We tried to extend the conversation with a few but inevitably failed. Our interests seemed destined to intersect only momentarily and were never intended to become any closer or more permanent. We eventually moved a few doors down the street from one of our early encouragers but never came in contact with them again during our relatively long tenure. That's just how Shoestrings work. They typically have no past or future but manifest for just that particular moment.

My dad kept track and sent birthday and Christmas cards to his Shoestring relatives. He possessed an exhaustive understanding of his half-siblings and their extended families. My mom knew her Kennistons from her Mayfields, her grandparents having first been step-siblings before old AJ Mayfield, Junior, married the widow Kenniston. That family tree looks like a tristed Bristlecone Pine to me. I remember happening upon a second cousin from that clan when I was working in Manhattan. He'd made quite a success of himself managing insurance processing systems. He passed a few tips he'd learned from working with a vendor we shared, and I've never heard from him again, which is typical of connections with Shoestring relations.

I speculated that, about a year into my first great Exile, one could take any interstate exit and, within about a year, feel at home there. What might start out as a region of strangers would fairly quickly resolve itself into Shoestrings and threads, some of which would inevitably become friends. We are less separate than we might imagine. Us introverts struggle to imagine the connections that surely link all of us here. E Pluribus Unum works the other way around, too, for the many we mistake for undifferentiated others, certainly originally came from one. In this way, we're probably somehow all Shoestring relatives.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved