TheWiseKing

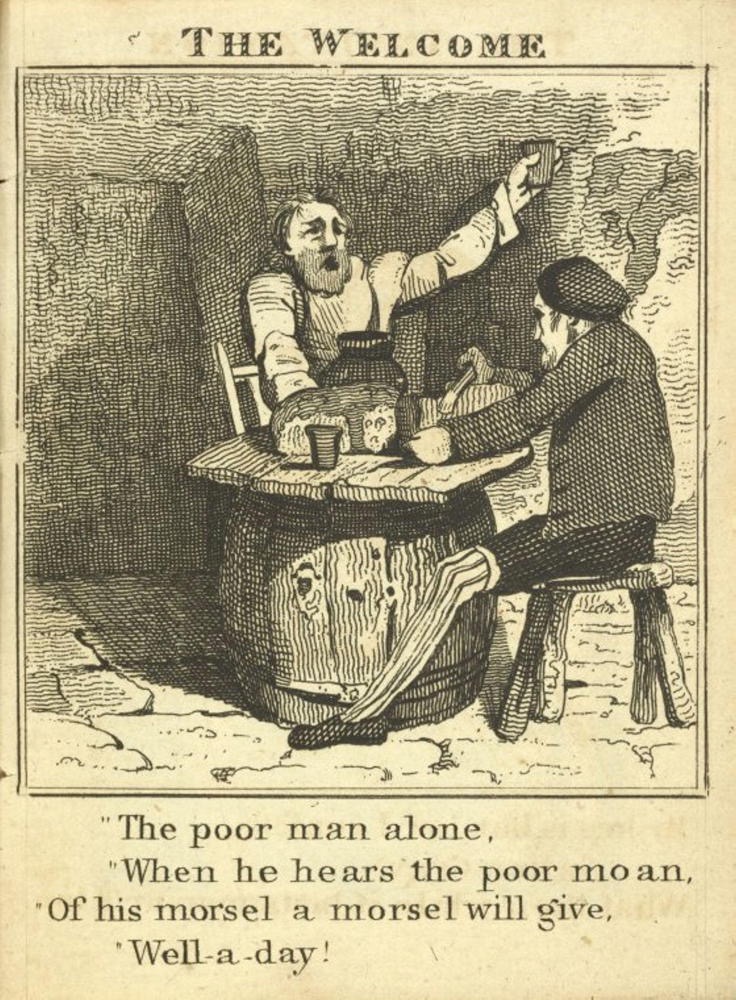

Thomas Holctoft: The Welcome (1806)

from Henry Fielding's 1742 novel

The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews

and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams.

"He obviously had no viceroy insisting The King Is Wise."

Our incumbent has taken to referring to himself as King. He'd starting making "kingly" pronouncements from his first day in office, though most of these seemed eminently ignorable, just so much bluster. But the delusion seemed to expand as his tenure lengthened, culminating in a self-published magazine cover depicting him in an ermine-trimmed coat and crown. He'd replaced Time at the top of the cover with his name, as if to amplify the depth of his growing delusion. He performs like an eight-year-old might, aching for a sword fight. He looks ridiculous, though he doesn't seem to notice, for few experiences are more entrancing than such imaginings. To elevate oneself more than entrances, it quite literally ennobles. It's all delusion, of course, but the most uplifting sort. The notorious madness of kings originates in just this way. Even those who inherit their crown are subject to this come-down, for the limitations of every charter tend to far outweigh the power they bestow. Real kings learn in their earliest training not how to cope with great authority but how to cope with the more humbling reality of their situation.

They learn that they were born more figurehead than anything. Their inherited authority remains primarily imaginary. Their responsibility will include overseeing machinery far beyond their reach to inspire more than demand compliance. The crown's wishes, then, had better closely match the will of the people, for they far outnumber the royal household. Those instances in history where a king misjudged his vassels' interests tended to end poorly for the king. Contrary to all pomp and circumstance, the king remains the people's servant, not anything even approaching omnipotent.

Kings only come in two varieties: wise and foolish. The space separating each might prove miniscule in practice. TheWiseKing listens to his councellors, who serve as extensions for his senses. TheWiseKing understands that he can perform little fact-checking because the gravity changes whenever he enters a room. People will always remain much more likely to confide to him what they believe he wants to hear rather than what they might suspect he needs to understand. TheWiseKing has compatriots across the land chartered to speak hard truths to his presumed power. They confide what everyone else tries to hide. They provide the permissions TheWiseKing requires to succeed in his mission to successfully rule. They allow him to see through walls and therefore seem both prescient and human to "his People."

Foolish Kings don't do any of those things. They believe themselves to have been divinely inspired. They were probably spoiled by overly-attentive nursemaids when they were a child and, perhaps, never told the truth about being perceived as powerful. It's fine when others believe a king to be strong, but never wise, or even advised, for any king to topple into that conviction themselves. However grandiose their public persona, they must remain a humble penitent inside. Haughty kings have horrible endings. Arrogant ones, even worse. Beneficence better supports a lengthy reign, generousity and compassion, a happy one.

A good king develops thick callouses from ignoring so much beyond his practical influence. Take the Spanish Empire, for instance. It lasted for over five hundred years and spread around the globe. It was administered by the king, employing a network of local viceroys. Viceroys were more than merely their king's local representative. They were the king in practice in their locality. While they absolutely took direction from their king—to whom they reported directly without any middlemen—they were also charged with interpreting their king's direction. This work was complicated by the slow communication of the day, when it might take a year or more for a viceroy to receive their king's response to any inquiry. The local situation might have dramatically changed since the reported native insurrection headlined in the prior report. The king's response might command the viceroy to put down the rebellion, even though the rebellion had needed no putting down in the interim. By then, the viceroy's son might have wed the local chieftan's daughter, resolving any future problem, so the viceroy understood their King to be wise and didn't do as he had been ordered.

TheWiseKing is created by his viceroys, who learn to interpret his explicit directions exclusively in ways that might make their king seem wise in practice. Viceroys would never refuse to obey any direct order they received from their king, however outdated. Instead, they would consider what interpretation might best render that order wise in the then-present circumstances. This might appear as if the viceroy sometimes disobeyed orders, but in practice, this was always and only the viceroy rendering his king wise. TheWiseKing learned never to second-guess their representative on the ground, for their perspective from their distance couldn't possibly have been superior to their viceroy's on that ground. The watch phrase among the viceroys over those five hundred years the Spanish empire flourished was, "The King Is Wise." And so he certainly seemed.

Our more modern counterpart, who was elected president but insists upon playing dress-up, couldn't be more different from the ones he cosplays. He does not spend his days listening to wise counselors. He ignores his allies’ advice. He believes himself more prescient than any of his imagined role models ever were in practice. In theory, being king involves radically different things than it might be in practice. Practice entails little of what imagination might anticipate. Being king demands a unique kind of professionalism. The cut of the ermine-lined coat discloses nothing. The Man Who Would Be King exclusively wears The Emporer's New Clothes. He stands buck naked before his people and does so without showing shame. He knows he cannot hide behind the wardrobe or, really, successfully hide behind anything. Either he's a man of the people, or he's nothing. Kingship differs little from democracy in practice. It was only the violation of long-standing kingly policy that ever inspired our founding fathers to take charge. Had King George III understood who had always been in charge, he might have been remembered as wise. He became a despot instead and thereby lost his most promising colony. He obviously had no viceroy insisting The King Is Wise.

©2025 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved