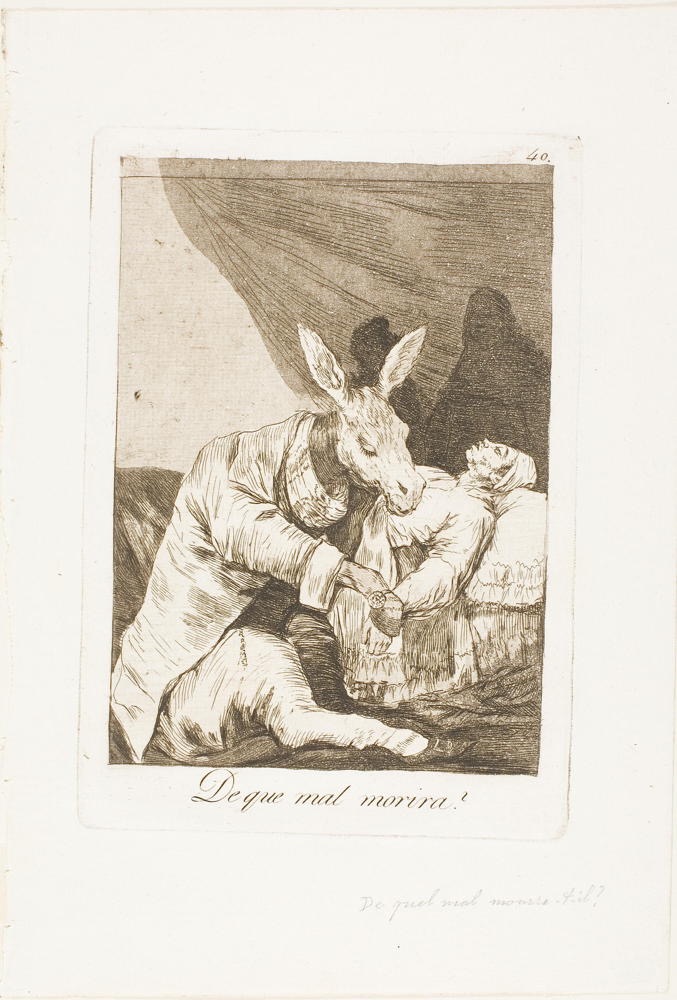

Untreatable

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes:

Of what ill will he die?, plate 40 from Los Caprichos

(1797–98, published 1799)

" … the lesson that seems to need to be relearned anew every time."

Being Exiled does not amount to a treatable condition. It is not a problem requiring a solution, though I first considered it a serious problem. I spent considerable nonrefundable time needlessly and fruitlessly seeking a solution. My life became a parody just as certainly as if I had awakened to find myself cast in an old I Love Lucy episode. This experience might have been tragic. Indeed, it seemed as though it certainly could have become tragic. That it didn't, or eventually didn't, amounts to a form of magic. I certainly contributed to the comedy of errors. I sought salvation from what I might have more productively considered a mere flesh wound, a scratch. I blew my condition out of proportion and then blamed the Gods, the universe, or my ineptness for cursing my meager existence. I felt cheated, wronged, and violated. I was the one wielding the weapon, though. I was burgling myself unawares.

In this life, stuff happens. Often, no perpetrator exists, no prior intent. One minute, it's one way; the next, it's different. The absent thief and the missing intention are easily projected onto the situation, creating what sure seem to be credible presences. Plot development depends upon somebody setting out to chase the perpetrator with the clear conviction that such a character exists. Often, one doesn't. A shadowboxing context ensues where the villain somehow manages to stay just out of reach, though the failure to find and punish frequently becomes a justification for continuing the pursuit in ever greater earnest. These minor failures add to the initiating frustration, further escalating the relative importance of eventually finding the perpetrator who was never there. Iterating beyond reason seems common in these situations, for what might tip the seeker off that they're their own victim, victimizer, or cruel judge?

Only after I got thoroughly tangled up in my own misconceptions did it start to occur to me that my Exile was not some grand conspiracy to humiliate me. It eventually began to seem as if my Exile might not have been very much about me at all. Still, the crime had clearly seemed to have been committed, and I had obviously been cheated. There I was, adrift in an indifferent world, suffering from something, certainly suffering. I had thought I'd reasonably diagnosed the cause, but causes do not always suggest a treatment. It rarely follows that any apparent cure accompanies symptoms. Especially in victimless crimes—the cases of The Normals—effective treatments might range from ineptness to sincere indifference. As the crime fades in importance and initial differences fade into familiar patterns, it might occur to even the more deeply wounded that only their heart was pierced, and not out of anyone's malice.

It was a lover's wound, the kind inflicted by misbegotten caring. The kind only ever inadvertently administered, often after mistaking some incoming information as a wholesale redefinition. Once an outside receives the power to define anyone's interior, a sense of inferiority can't hardly help but result. The resulting one-down and two-back position could convince anyone they're the undeserving victim. That was not redefinition, though, only information, and perhaps nothing more than trivial information essentially worthy of ignoring. But Being Exiled seems significant enough to interpret as a particularly substantial crime, a felonious offense against most of what anyone might hold dearest. The separation of self and estate berates; it goads the presumed victim into constructing their fate and blaming it on other actors than themself.

Life might have always been about uncovering these damaging acts of self-deception. If one grows, one certainly outgrows much of whatever reigned before. One comes to see differently. One discovers their former Gods were mammon, and this pattern can reasonably continue far, far into anybody's future. Vitality seems to depend upon us outgrowing almost everything, with each fresh realization potentially rendering even the strongest among us absolutely impotent. I have grown through the assertive aegis of my former ignorances. I have discovered my darkest distresses to have been compelling illusions. I have broken my own heart so many times that I should not trust myself to handle it anymore. But there are no others, only the inept owner who seems to learn only by burning himself first. There was never anybody else.

Our Exiles, like our trespasses, might exist only to better inform us. They cannot definitively redefine, for they exist as no more than relative conditions. They do not delineate the end of anything but illusions, though illusions seem plenty powerful when it comes to encouraging misconceptions. Every Exile disrupts some entrenched status quo state. Each uproots old familiars, replacing them with clear inferiors, none of them capable of filling the suddenly so obvious void. They are the beginning of the end of a satisfying delusion, as each conviction perhaps must become if we are to continue growing. The moment Being Exiled doesn't take your breath away might be the moment you pass away. How anyone recovers their respiration must remain a persistent mystery, for that difficulty's always resolved by a smothering protagonist who's probably clueless about their illness and its treatments. That the condition is just another one of The Normals and therefore remains Untreatable becomes the lesson that seems to need to be relearned anew every time.

©2024 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved