Duh-fficiency

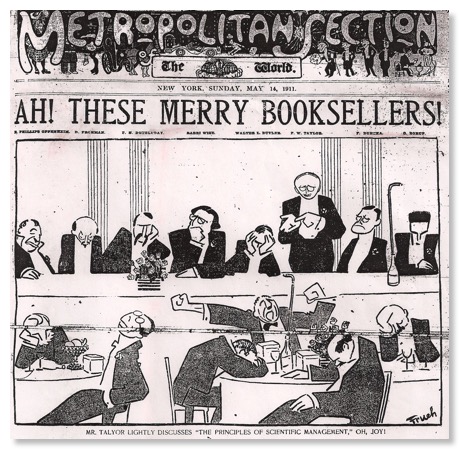

[Drawing from the May 14, 1911 New York World, reporting on best-selling author and The Father of Scientific Management, Frederick W. Taylor’s after dinner speech at the American Bookseller’s Association convention.)

A hundred years ago, the world was in the middle of going crazy again. It’s not profound to notice that the world goes crazy sometimes, but this crazy was special. Usually, these insanities disappear quickly. This one did not. It managed to worm its way into our DNA and replicate until today, this crazy has become the accepted benchmark for sane.

What was this insanity? Efficiency.

Like most crazes, efficiency crazy started innocently enough. A big fat juicy idea. If you’d seen the typical factory workbench circa 1911, you’d understand the fertile ground this small seed fell into. You would have seen a disorganized mess! Parts and tools cast where ever they happened to land the last time they were used. The central organizing principle was a physical Rorschach test not even the individual worker could ever comprehend.

Management, that emerging class of “shiny-seated Harvard boys,” had what appeared to be a genuinely better idea. They would organize the workplace efficiently, from the Latin word ‘efficere,’ to bring to pass; bring about; effect; execute. Curious that these budding efficiency experts didn’t actually do the work, but chose a label for what they did do that claimed credit for effecting.

What they did do was organize. They classified and codified, created streamlined records-keeping schemes, and following the inspiration of Melville Lewis Kossuth Dewey, who devised his Dewey Decimal System to efficiently organize libraries (and who also spelled his name Melvil Dui for efficiencies sake), invented inventory control. They analyzed the workers’ motions, seeking the one best way to behave. They cobbled together sciences that today appear positively medieval to create a grand delusion, the science of management, creating a technological elite equal, then surpassing even the status of the old money elite.

Very little of this work began as crazy. Fifty years later, it had become pathological: a logical, rational pathology. Now, I’m very afraid, it’s metastasized.

As David Halberstan reported in his 1986 Reckoning, speaking of one of the later-day efficiency experts, “McNamara sought rationality in an irrational world, and if he had had his way he would have manufactured and sold only rational cars.” But, he continued, “there was no easy way to replenish real car men,no graduate school readily turning out designers who were both creative and professional or manufacturing men who could run a happy, efficient factory. People of instinct and creativity, really talented ones, came along only rarely. The great business schools of America could not produce genius or intuition, but they could and did turn out every year a large number of able, ambitious, young men and women who were good at management, who knew numbers and systems, and who knew first and foremost how to minimize costs and maximize profits.”

What would a decade later degrade into the principle component of The Fog of War had already chewed well into the center of American business.

The ancient Greeks understood the principle of Enantiodromy, the transition of things into their opposites. What began as an efficiency movement has, through repetition been elevated into ideology to become its opposite, what I’ll label Duh-fficiency. Materially deficient. Stupid-making. A resounding slap on the forehead of progress.

At its inception in the middle of the great industrial expansion, efficiency became the over-riding meme of my grandparents’ generation. No one was untouched. Church bulletins published guidelines for becoming a more efficient Christian. Homemakers were exhorted to make efficient meals. The alternatives were wasteful, unmodern.

These humble beginnings produced fast food, the Reader’s Digest, Tin Lizzies, and tasteless beer. Jello, breakfast cereal, instant everything. Aided and abetted by efficiency-minded academics, markets were declared both rational and efficient. Business became America’s business, America’s obsession, America’s strange attaction. The land of the free morphed into the land of the efficient. The home of the brave became the home of the efficient.

As Judith A. Merkle noted in her Management and Ideology: The Legacy of the International Management Movement, Scientific Management “provided management with a technique of control that had no intrinsic limitations, making possible a quantum jump in industrial exploitation.” Not to mention the bureaucratization of even government. The bureaucracies we both rely upon and endlessly complain about started there, as efficient government.

Even the universities took up the banner. Merkle notes that while the professors wanted to teach this new science, they rejected the idea that they might be managed under its schemes. “thus it was not the engineers, but the academics purely in the business of organizational analysis, planning, and the teaching of management who became the advocates of the conscious message of peace through productivity ...: the strategy of creating and monopolizing bodies of knowledge as a means of perpetuating and expanding professional job opportunities.” A self-licking ice cream cone.

”[I]n the United States, as in Europe, the possessors of active minds who had their eyes fixed on middle-class gentility tended to pin their hopes for social mobility on their unceasing labors to create sciences out of services.” Proliferation was absurdly simple in a frantically upwardly mobile society, and many bright young men achieved gentility by setting down a body of arcane but marketable knowledge, gathering disciples, setting up a school, establishing ‘professional’ certification, and founding a professional society.

We all know where this story goes because we live in the future these bright-eyed geniuses aspired to. We’re so efficient now that we’ve had to forfeit our middle class gentility to maintain it. Our new computer’s on back-order because an earthquake in Japan shut down a node in a giant just-in-time manufacturing system that looked a whole lot better on paper than it turned out to be in practice. What was once merely service has evolved into accepted, inevitable science, but a virulent and pervasive pseudo-science. Duh-fficiency.

Will we, can we reverse this trend our own innumeracy created? Or will we choose to simply accept as inevitable the heartless inflections of our small and mindless god, the god of efficiency? Duh-fficiency.

I believe that there’s a way out of this cul-de-sac. The first step involves acknowledging just how dead this particular end must inevitably be. This is no small step. Beyond that lies if not entirely unimaginable, presently unspeakable alternatives. I can’t even hint at what those alternatives might be. Yet.

Stay tuned. There’s a lot more to come....