Hardworker

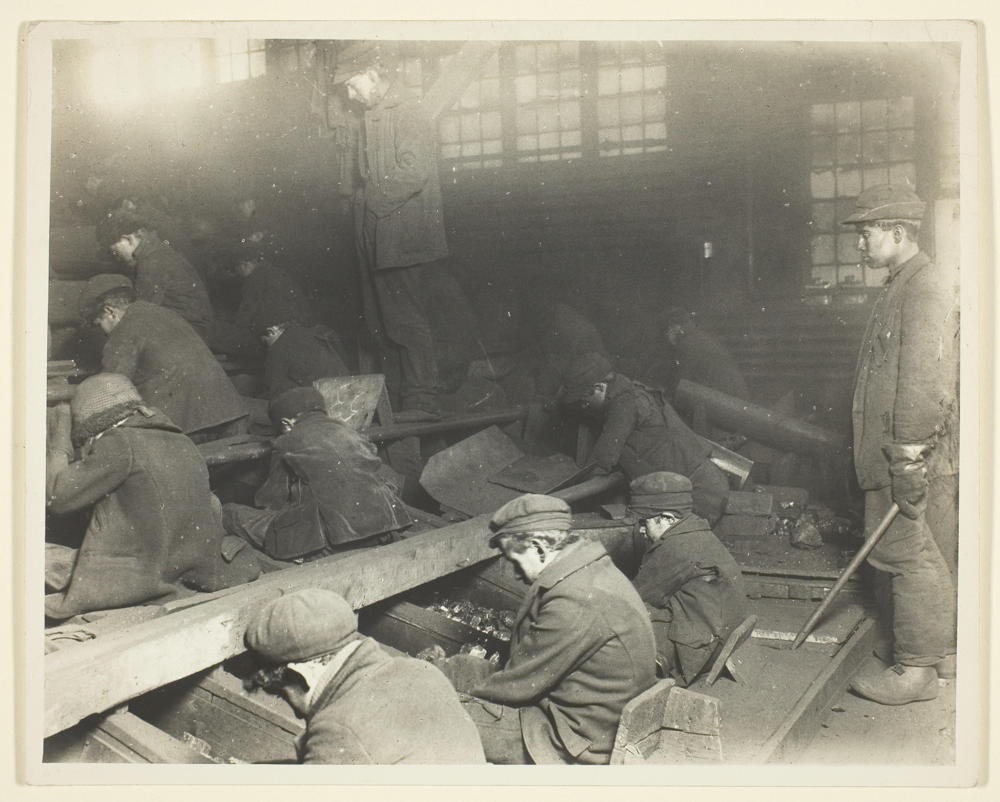

Lewis Wickes Hine:

A View Of Workers In Ewen Breaker

Of Pennsylvania Coal Company (1911)

"One might, with practice, even eventually become an EasyWorker sometimes."

Whatever the profession, in this culture, we expect every practitioner to be a self-proclaimed HardWorker. Hard work, as opposed to all the other kinds of work, seems to be an integral part of the much-touted and probably mythical American Way. If we're not killing ourselves to maintain our existence, our existence ain't worth much. HardWorker seems to be the essential marker of morally upstanding people, too, for lowlifes seem best characterized as slackers. HardWorkers have no time for lowlier pursuits. They're tuckered out by the end of their shifts.

Curiously, the HardWorker designation belongs to more than just the exhausted laborer. Lawyers, doctors, and even administrators are free to characterize their activities as HardWork, although few return home with grass stains on the knees of their jeans. They might be laboring over a well-lit desk, moving papers more than shoveling unwieldy loads of coal. Still, they, too, consider themselves self-sacrificial, doing themselves in to eke out their living. Even the erstwhile banker recalls their career as a HardWorker struggling to overcome obstacles to successfully clip coupons and foreclose on errant mortgages. The HardWorker ethic promotes the notion that a worker's reward will be found in Heaven. Until then, one maintains one's standing by working. Those who do not hold "good" jobs with self-sacrificial dedication are never considered upstanding citizens.

In the real world, of course, even HardWorkers take breaks and allow themselves to take well-earned vacations where they might even dabble in acts of idle debasement. In practice, people work in spurts and slacks, advance through fits and starts, and succeed despite serious shortcomings. Successful careers tend to include lengthy periods of unemployment where even a HardWorker finds himself idle. He might struggle to recognize himself in such straits and attempt to compensate by idling harder, whether that adds value or not. This culture expects an obsessive response to every circumstance, however paradoxical that becomes. Those who retire from successful careers might find themselves depressed at the sudden absence of assignments upon which they can continue to crucify themselves. An actual HardWorker's work should never be done.

Many of us carry the HardWorker curse and struggle most with idleness. A day's off seems more punishment than reward, the lack of an explicit assignment, sheer agony until displaced with another demand. We might not consider planning a valid form of working and might even consider reflecting just an awkward form of slacking. I was raised to become a mindless adult, only truly mollified by purifying work. A job was considered more important than an education. A paycheck, validation. A backlog, the only social security worth possessing. Accomplishments, the only valid evidence of living.

As an artist, I struggle most with the innate idleness artmaking entails. It's not all doing, but considerable considering, apparent idling, producing nothing for the longest times. There's no rushing inspiration, and one learns through painful experience that until it's fun, whatever they're pursuing might be better left undone. The long periods of cogitation might feel like the hardest form of HardWorking, but it honestly appears more like shirking, even to the practitioner engaging in it. One must learn to judge oneself by means other than Puritan, to become much more generous and forgiving if they feel they must remain judgemental. A beard is not merely evidence that its owner was too lazy to shave. Ten thousand alternative ways to maintain one's standing exist besides the tired, old, reliable HardWorking. One might, with practice, even eventually become an EasyWorker sometimes.

©2023 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved