Insubordinate

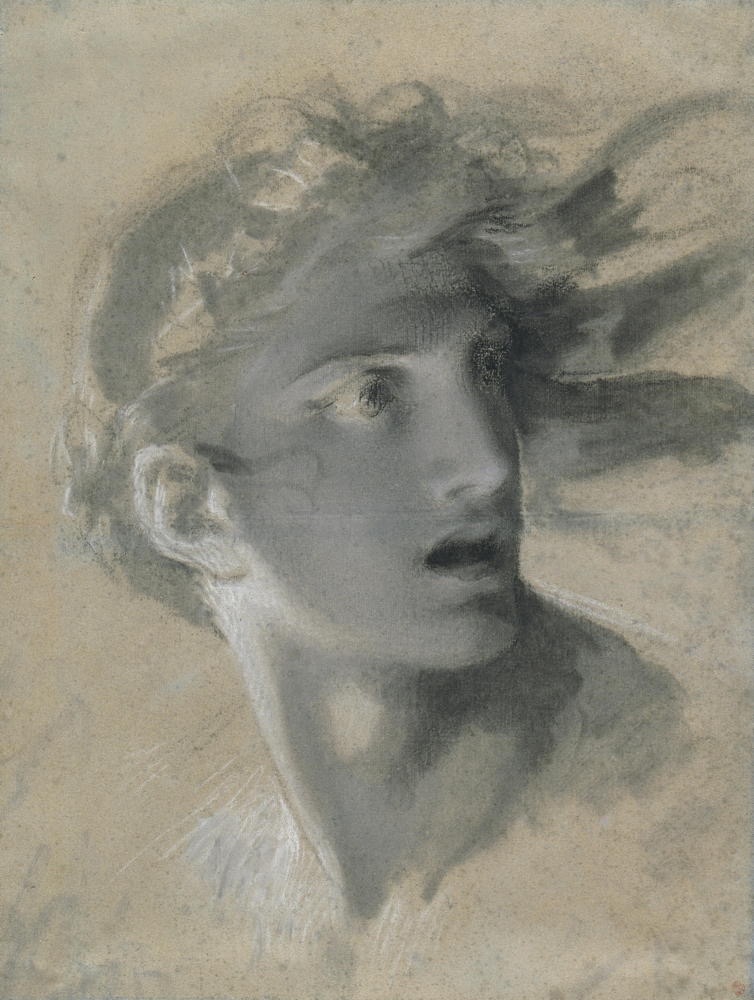

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon: Head of Vengeance (c. 1804)

ABOUT THIS ARTWORK

A study for the figure of Divine Vengeance in Prud’hon’s celebrated paintingJustice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime (1808), the head of Vengeance, who pursues Crime as an agent of Justice, brilliantly reflects the artist’s stated aim for the painting: “to give a commotion to the soul.”

Although the drawing’s blue paper has faded almost completely to gray, the work’s expressive power remains intact.

——

"The Decent direct themselves for their own damned reasons…"

Decency must be an Insubordinate act. It cannot be ordered or productively insisted upon, but must be more or less freely chosen by the individual engaging in it. One may take instruction in its practice, though this offers little beyond a grasp of its underlying concept. Practice proves different in actual practice and utterly depends on context, which shifts so that any two instances might prove the opposite of being indistinguishable from each other. Even experienced practitioners often wonder if what they just tried really represented the Decency they intended. Not even the receiver can always confirm receipt. So much of its delivery depends upon intention, which often necessarily remains implicit. Decency frequently appears in unexpected guises.

Indecencies can easily be coerced. Many indecent acts stem from out-of-context commandments, attempts to deliver the likely impossible in a specific context. The big f-ing hammer employed in the attempt to comply adequately explains why these so often go awry. The hierarchies themselves might well be the primary source of indecency, since individual actors struggle there to be properly Insubordinate. Well-ordered frequently seems synonymous with indecency, though it’s usually intended to be its opposite. It might be that any subordinate act undermines the potential for Decency to manifest. Those who merely follow orders break some necessary underlying order necessary for Decency to thrive. To be truly alive might require Insubordinate action.

If these statements are true, Decency demands much from each of us. It insists that I make up much as I move through life. It means that I must be responsible for my Decency, for nobody can rely upon becoming Decent merely by association. Decency’s subordinate never becomes Decent by even the closest association, but by some Insubordinate action, one they own alone. These often come in moments of extremity when the Decent thing might seem impossible to produce. These usually seem embarrassing, if only because they break some well-entrenched patterned behavior. I believe that much of the indecency we witness comes not from volition but from mindless repetition, from merely doing the most familiar thing in response to, perhaps, some extraordinary situation. One reacts rather than responds. One misses an opportunity to contribute some Decency, but not by necessarily plotting to commit gross indecency.

Decency feels compelled to color outside the expected lines. It can and sometimes does occur inadvertently before, shockingly, producing an unanticipated outcome. Then one can build on that happy accident, not necessarily to repeat the same action, but to gain inspiration from the success that came from choosing a different response. The possibility always exists to do something different, especially when it seems impossible to do something different again. Decency often demands more creativity than anybody would readily contribute. It demands difference from a world most often obsessed with producing efficiency. It seeks to break a habit to create insight, perhaps delight, though Decency, even when properly made, might disappoint. Decency can be mighty messy.

Ultimately, everybody gets to say what constitutes their Decency. It might be that nobody else even notices my attempts to get stuff right and improve over prior attempts. Only I am ever qualified to judge the quality of my Decency in practice. Decency is not a spectator sport. It’s not trotted out to receive applause. It remains largely a private act, a wrestling match between convention and often haphazard invention, judged only by the actor’s intention, by the actor himself. The absurdity of even a priest insisting upon a parishioner’s Decency appalls me, for it produces a paradox. Nobody can insist on another’s Insubordinate act without stealing their ability to make the sort of choice that really matters. The Decent direct themselves for their own damned reasons and might well appear Insubordinate when contributing their best.

©2025 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved