Recipe

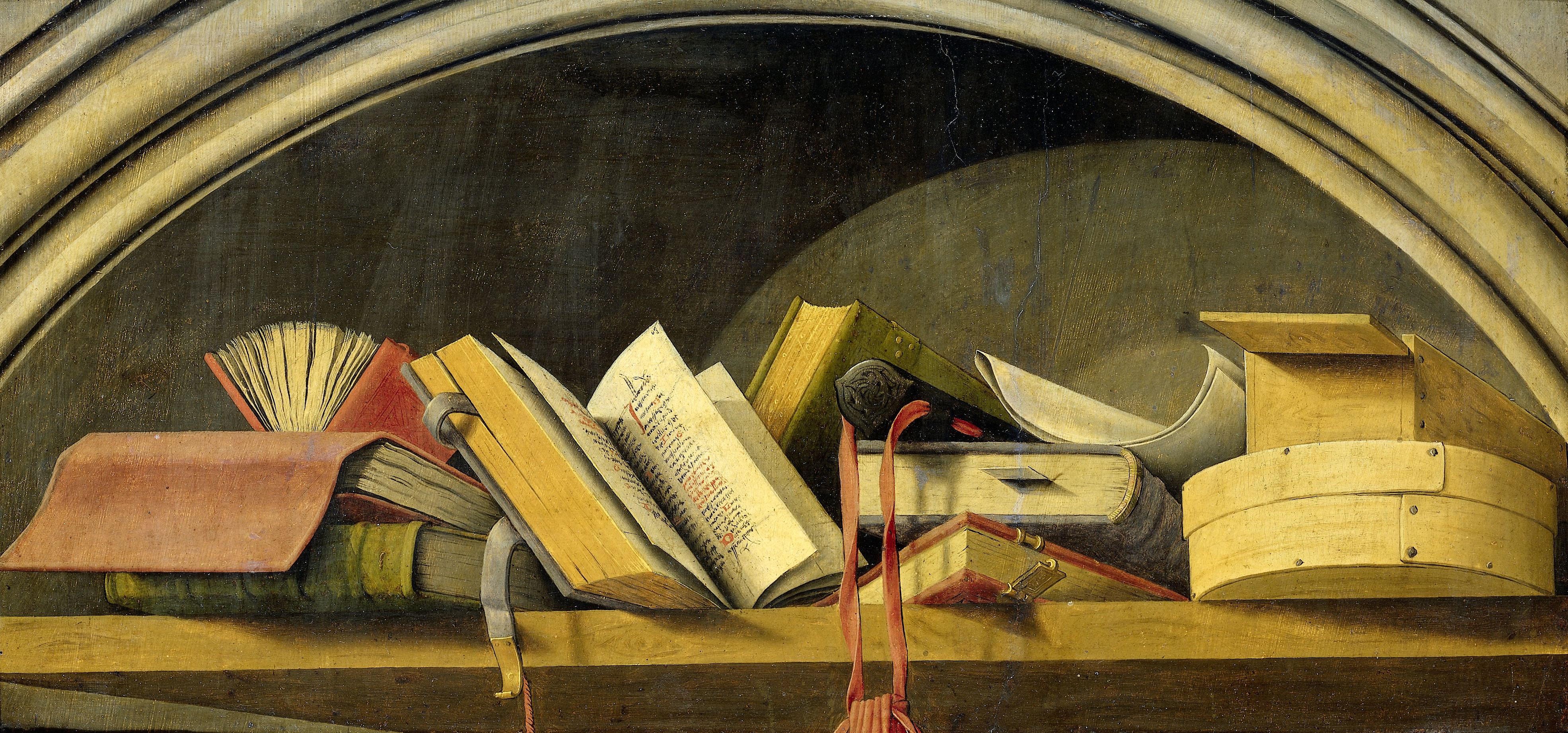

Barthélémy d'Eyck:

Still Life with Books in a Niche (1442 - 1445)

" … I will struggle to respond."

©2022 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

I am sometimes asked to recite a recipe for something I've made and I always struggle to respond because I don't usually use recipes. Oh, I might reference one to understand proportions—how much water to how much rice?—but I rarely very slavishly follow any instructions. Recipes seem the very epitome of frozen action, listing stuff as if stuff could be listed, sequencing actions as if sequence mattered. Consequently, I do not bake things because baking is too exacting, demanding slavish adherence to rules which successfully distill action into script. I'm not that kind of cook. For me, cooking seems more discovery than recitation. I'm never quite certain how to cook anything. Even if I've cooked something similar before, I've forgotten precisely how I prepared it and I did not write down my discoveries. I consequently do not cook the same thing once, let alone twice.

I am a man of simple tastes. I maintain a rather deep larder, largely stocked with components: three kinds of rice, four kinds of corn meal. I combine these components as my mood dictates, as they seem to want to fit together. I'm forever dredging up something that was mouldering on some back shelf to make the surprise showcase of some otherwise pedestrian midweek supper. I am resourceful, with a long and terribly imperfect memory. I recall in snippets, each of which go on to suggest accompaniments, which eventually become supper. I'm lucky if I even remember the components I used and I never produce a written recipe, which is why I stall whenever I'm asked to recall how I put some dish together. I just do not remember.

I cook by instinct. Last night's supper, a Supper Of The Lamb, in that it used up the rest of that leftover bone-in leg of lamb, might serve as an example. This was a typical supper in that it used my usual first ingredient. (I almost always use the same ingredient in everything I cook, and that is 'whatever's threatening to fester in the larder.') That lamb was not growing penicillin yet, but it would be before the week was out. There are probably ten thousand different ways to create a lamb stew and I didn't refer to any of them to gain inspiration for creating mine. I had begun with a surprise ingredient I'd never used in anything before, onion tops. I'd harvested my small crop of Walla Walla Sweets and ended up with a pile of tops, the greens, which I'd chopped up and thrown in the stock pot with water and left simmering in a slow oven overnight. That mess smelled great, but lacked body. It was literally just oniony water, unsalted. I drained off the worn out veg and left that water simmering while I went out shopping.

I did not go out shopping with the idea of purchasing ingredients for my Lamb Stew. I knew that I had plenty of variety already in my larder to produce a passably finished dish. I went shopping because it was Saturday, Farmers' Market Day, and I was interested in what they'd dragged in for sale this week. I found some carrots, purple and orange, and a bunch of yellow beets, all with their tops still on. I thought I could improve the character of that onion top stock by simmering off the carrot greens in the pot. Carrot greens produce a carroty scent when cooked, and are classified as edible but not very palatable when eaten either raw or cooked as a vegetable, but they make a perfectly passable addition to a stock pot. I threw those in and added the leg of lamb bone for additional texture, along with some fennel seed, licorish root, and burdock root for scent and flavor. I left that mess, all disposables, to slow simmer for a few hours, and also started a small pot of garbanzo beans on a back burner.

Garbonzos are magical. Their cooking water alone improves the texture of any meatless stock. It helps the meaty ones, too, adding richness and a slicker mouth feel. I would puree those garbanzos and add them to the finished stew just before the final simmer. I slow baked for a couple hours the yellow beets along with three large Yukon Gold potatoes. The potatoes turned waxy and would retain their pleasing texture no matter how long they later simmered in the finished stew. The beets, too, would never turn watery in there. The baking had rendered them almost leathery and uncommonly sweet, peeled, they would become a perfect playmate for the tender chunks of lamb.

A couple of hours before supper time, it was time to assemble the final mess. I drained off the carrot tops and spices, retaining that bone. I had produced perhaps a gallon and a half of thin stock with a very rich aroma. I peeled then cut the potatoes into satisfyingly large chunks. Ditto the beets. I chopped plenty of carrots and two fresh onions. I peeled a fresh head of garlic I'd also found on my foraging foray, fresh dug that day and still sticky. I had to separate the cloves with a paring knife. Ilsa, the farmer who'd grown the garlic, warned me that it was HOT! I pureed the garbanzos and poured that froth into the pot. I chopped those beet tops and added them, too. Lastly, I cut up the remaining lamb, also into satisfyingly sizable chunks, then set the pot back into the slow oven to finish simmering.

The Muse salted the stew, which, as I usually do, I'd produced without adding any salt. I have no taste for salt. I cannot determine whether more's needed. The Muse can testify that if I've cooked it, it very likely needs salt. She quickly finds the proper proportion and offers me my first taste of the developing stew. I do not usually taste whatever I'm cooking as it's developing. I can almost always tell how it will taste by how it smells. I can more easily tell when something's done by how it smells rather than how it looks or tastes, so I follow my nose when cooking. Noses don't translate well into written instructions.

This Recipe, then, turns out to have been a sort of scavenger hunt, a serial synchronicity, an unlikely emergent causal chain, a full body and soul engagement. It started innocently enough, with me having some onion tops I didn't want to just throw into the composter. I'd never made an onion top stock before, but I couldn't see why I shouldn't. It was almost as if the scent of that stock began attracting its companions. Stuff just sort of fell into my hands and from there, into the pot. Preparation took about twenty-four hours. It could have taken longer or less time, it took just as long as it took. It felt timeless.

The Muse went out to find some wine during the stew's final simmer. Not wine for this supper, but for one we'd been invited out to later. She returned, though, with as perfect an accompaniment as anyone could have imagined, a simple, fine Portuguese Douro, a lamb stew wine if ever there was one. The wine completed the synchronicity and so the supper. I won't mention here the gooseberries The Muse picked off our new gooseberry bush on her way back from the composter. They were dessert, a happy and tart surprise and the perfect coda.

I doubt that many recipes produce what this supper produced, a deep sense that, in spite of all this world's troubles, deep down, something's right with this world. The reassurance that comes from "accidentally" bumping into the perfect ingredients at the perfect time and with those, producing a perfect supper, ennobles everyone around the table. Someone's almost certain to ask after the recipe for that and I will characteristically struggle to respond.