Ungrokability

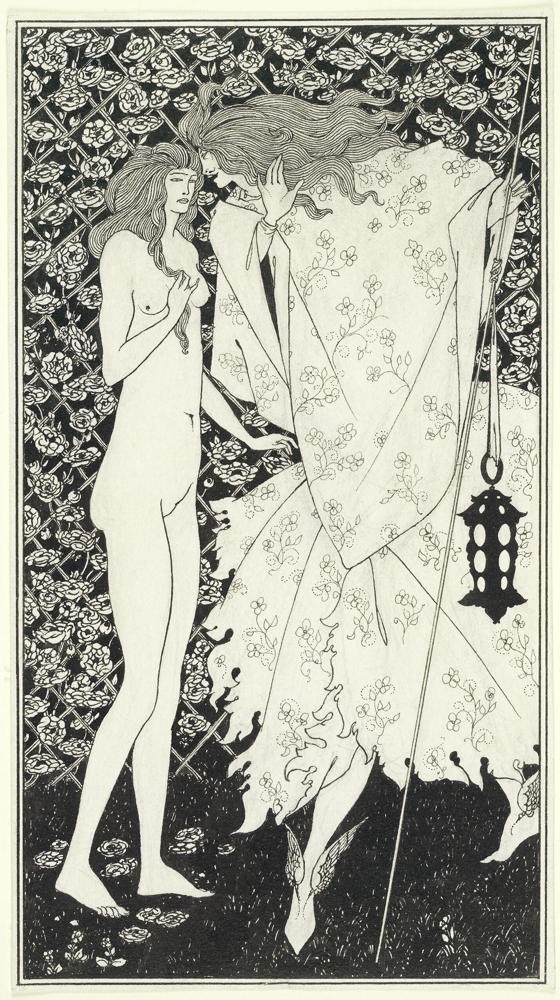

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley: The Mysterious Rose Garden (1894)

"I have no great need to resolve any of the greater or lesser mysteries in life."

My greatest humiliation I experienced when finally pursuing higher education occurred quite innocently, in a beginning Calculus class. Why the university imagined that anyone pursuing a business degree might need calculus was not for me to question, for I quite literally knew nothing about higher education. I was fortunate to have been deemed Not College Material by my high school guidance counsellor, so for seven years, I’d never questioned whether or not I should pursue a degree. That decision was thankfully made for me when that kindly counsellor convinced me that I was not suitable. I set about planning my life around that possibility until seven years after high school graduation, when my first career stalled out, and I grew weary of working casual labour jobs. I decided that I might prefer to wear a tie to work instead.

I just enrolled in the closest state university, which accepted me sight unseen. I paid my tuition, bought my books, and commenced showing up for classes. I was directed to bonehead sections of most subjects, for my background, as attested to by my high school guidance counsellor, had not been academically stellar. I worked hard and received passing grades. I had not even a fading interest in receiving an A. I figured those were reserved for geniuses and overachievers. I hoped for a solid B and felt grateful when I received a C. I paid close attention and dutifully did my reading and homework assignments, and did okay until I found myself enrolled in that Calculus class.

The professor was a graduate student for whom English was not his first language. I struggled to understand anything he said, let alone the math he attempted to introduce. It quickly became clear to me that I couldn’t understand very much of what he said. I recognised little of what he tried to impart as belonging to the same food group as long division. I hazily remembered a few concepts from what little Algebra I’d taken in high school. I’d successfully faked my way through Geometry without ever once understanding the purpose of proofs, though I’d asked until I understood that my questions weren’t appreciated: “Just what are we trying to prove here, anyway?” I learned the concept of tautology, though, and graduated high school understanding that some subjects were securely beyond knowing, beyond grokability. They would remain mysteries.

I received a zero on my first calculus exam. The department head was alarmed and asked for a conference during which he determined that I didn’t have the background necessary to properly perform Calculus. I couldn’t explain to him how I’d parsed the problems, and he rejected my interpretations as illogical. I asked where someone might acquire the skill to properly interpret such problems, since it seemed clear that the textbook had failed to explain whatever it was trying to impart. He replied that I should consider retaking every math class I’d ever taken before, starting with whatever I’d taken before I was exposed to Algebra I, way back in seventh grade. His suggestion would have taken me more than the years I’d allocated to getting my degree to satisfy. He suggested that I might otherwise drop out of his Calculus section and go seeking another Science credit I might actually earn in lieu of total reeducation.

That’s what I did. I enrolled in a bonehead Physics section that promised no math and scraped by with a decent passing D because the final exam was 100% memorisation. I tiptoed my way through the balance of my degree requirements, never encountering anything nearly as daunting or mysterious as Calculus again. Once I’d graduated, though, I retained an interest in what had happened in that undergraduate Calculus course. I collected Calculus books with alluring titles aimed at convincing people like me that maybe we could be qualified to learn the subject after all. I was serially disappointed to discover that none of those authors had managed to master what seemed like the necessary precursor skill, that of knowing how to explain calculus without resorting to its own specialised language. Each seemed to subscribe to the idea that Calculus required full immersion in a world destined to make no sense. After serving a necessary probationary period, realisation would supposedly come on some odd, utterly unanticipated morning. Then one would know how to perform Calculus. None of the books coherently explained what one might expect to achieve from performing such an exercise, either.

So I failed again to master that arcane art form. A friend later confided that calculus, indeed, all of mathematics amounts to an utterly arbitrary language. It could be acquired but never fully understood, just like we acquire our native language, and some acquire foreign tongues. There are no why questions to be answered in such acquisitions. Acceptance seems to be required without many supporting answers. I found a book by a guy who claimed to have learned calculus after he retired. He had a niece who taught advanced mathematics at an Ivy as a tutor. I lost interest about three-quarters of the way through his journey. It had become too personal for me to appreciate or understand, though he sure seemed pleased with his accomplishment.

Much of what I encounter when scrolling through social media seems of a similar character: so lacking context that it must forever remain fundamentally Ungrokkable. If it seems understandable, it usually also seems unresolvable. No matter how many well-intentioned MIPs I might apply to resolving the mystery presented, I will fall short of resolving it. I get jinned up for another letdown. The exercise seems perfectly self-defeating. Like my relationship with The Calculus, that sense that I might somehow ultimately make sense of the mess motivated further fruitless inquiry, ultimately resulting in a backhanded kind of wisdom: the acknowledgement that mastery of that subject seems to be the sole purview of other people, not me. I might be fully capable of frustrating myself in pursuit of an understanding that would probably ultimately not be mine to gain. I figure that there are plenty of people capable of mastering The Calculus without my shadow ever coming close to crossing that threshold.

Such a resolution might be the most difficult for anybody to accept. I accept that Calculus ain’t mine to master, and that I’m no worse or better for that acknowledgement. Acceptance of such essential differences might be the foundation of the greatest wisdom. The alternative might be essentially an eternal struggle without resolution. I’m unsure what social media has that renders its content similarly Ungrokkable for me, but I am coming to acknowledge that it seems disturbingly familiar to my struggle to comprehend The Calculus. Some contests, some games, can only be won by refusing to play. It need not be an embarrassment to say that I’m not a Calculus person. I gave it a try and found the territory inhospitable. The absence didn’t limit anything I wanted to engage in. I still can’t voice a single practical purpose for deploying calculus, but then I’m no rocket scientist. I’m also not a computer scientist, and much of what they’ve wrought seems more focused on their interests than mine. I use my social media feed as if it were a sort of email distribution system, something requiring nothing more than a rudimentary understanding of addition and subtraction, with only very occasional need to understand multiplication or division. I aspire to keep the Ungrokkable Ungrokkable. I have no great need to resolve any of the greater or lesser mysteries in life. Then why do I keep returning to the scene of the serial crimes?

©2026 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved