Voicing

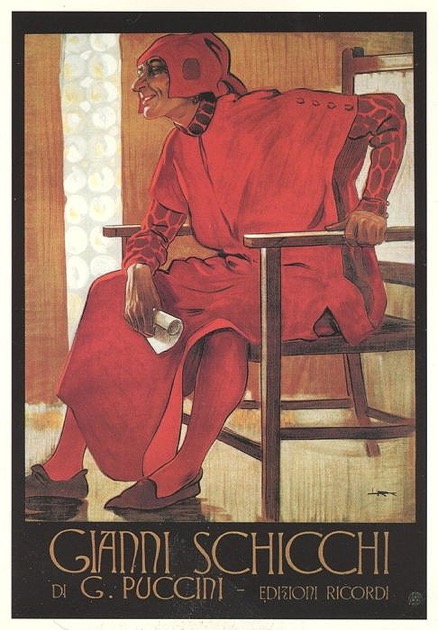

Leopoldo Metlicovitz, poster for Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi (1919)

"It might be that every authentic Voice sounds phony to itself …"

The first time I heard a recording of my voice, I felt embarrassed. I feared that the abomination I'd just heard had been a faithful reproduction of the tone and timbre everyone had always heard emanating from my pie hole. I felt appalled that I might have, completely unbeknownst to me, always sounded like … like … like THAT! And so I received my first great injection of self-consciousness, a virus, I suspect, and one from which I might never recover. From there emerges an inhibiting shyness on stages I formerly simply possessed. I could not hear that queerness when speaking or singing to myself, for some acoustical quirk spoiled fidelity, though my Voice sounded much better to me than that recording had sounded. I took to practicing in tightly enclosed spaces, bathrooms and closets, in hopes of better hearing how I actually sounded. I never lost that unwelcome awareness that I had never known how others heard my Voice. ©2020 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

I don't sing so much anymore. The arid atmosphere up here along The Front Range tightens up my throat. Even drinking a half gallon and more of water each day, I barely manage to keep my throat anything but dusty. When I try to use my voice, I first have to blow dust off it with over-much throat-clearing. I'm rarely called to use my voice these days. Pandemic isolation means I only infrequently speak, other than to the cats, and then, mostly in mumbles. I live in a mutely reverberating isolation booth where I think and write much more than I ever speak, and I only very, very rarely sing, even to myself, anymore. I used to routinely stand before rooms full of people and speak with authority all day. Now my Voice seems packed in mothballs in the unlikely event that I might need to use it again someday.

Learning that You Can't Tell Nobody Nuthin' might have discouraged my Voice. Oh, I could tell stories, mostly ridiculous ones, but I learned to avoid actually telling anyone something. I could not seem to clue anybody in, at least not to my full satisfaction, so I became mute on multiple subjects. I'd hold my righteous speeches for those few who requested them, and they seemed very few and ever further between. If I wasn't singing or delivering stirring speeches, the demand for my Voice reduced to almost nothing. A quick report-out about what I intended to do that day or a similar quick exchange to briefly recount where I'd been. My Voice evolved into a little-employed utility, barely a part of me.

I write instead. I hope to inject a sense of my Voice into the works I lay down, and I've many times thought that I might record myself reading my writing out loud, but the technology foiled my every attempt. Besides, that fundamental complication always emerged in that the recordings never sounded like me to myself. I even dabbled with injecting various electronic conditionings so my Voice might sound as though I was speaking from the bottom of a deep well or the center of an enormous concert stage, but I could never get away from the sense that I was listening to a recording of someone else, and someone who didn't hear my Voice well enough to adequately mimic it.

It might be that every authentic Voice sounds phony to itself, a dandy paradox which I suspect I'll never adequately unwind. I suspect that those who integrate their disconcerting self-knowledge might hold a comparative advantage over those who cannot. It might be that getting over one's self involves shedding that initial self-consciousness and simply getting on with it. I'm always uncertain if anything I've said was received as I intended, so it seems only a small extension to come to accept that the Voice they hear will always be remarkably unlike the one I hear speaking. I suspect that too much thinking along these lines could render me utterly speechless, which might just leave this world better off, anyway.