ZenosReality

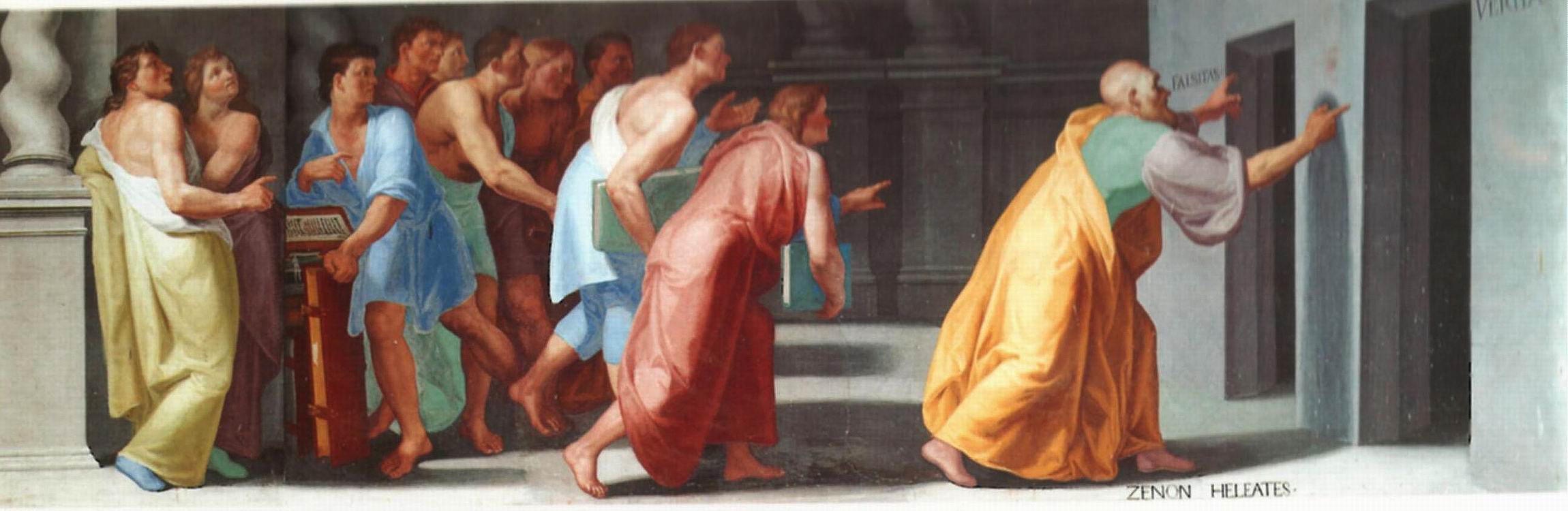

Pellegrino Tibaldi: Zeno of Elea shows Youths the Doors to Truth and False (Veritas et Falsitas) (C.late 1580s)

Fresco in the Library of El Escorial, Madrid

" … we might never notice ourselves incapable of stepping into the same river once."

©2022 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

It has long been a popular pastime among mathematicians and logicians to poke fun at the humble Zeno of Elea, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who left a memorable, subtle, and profound legacy of observations. He was the one who posited that one can never step into the same river twice and also the guy who cared enough to ask after the barber who shaved only those who didn't shave themselves, and wonder who shaved that barber's chin. Zeno pointed out how no arrow could logically hit any target, since each would subsume its progress by halving remaining distance, which could never logically resolve into any end point. His observations are today usually seen as provocations, interesting if largely irrelevant little insights into the limits of logical reasoning when explaining actual experience.

But we are not merely logical beings. Our experience should have demonstrated that we're paradoxical beings, too. We easily describe ourselves entering that same river twice. We often tangle ourselves in our own metaphorical underpants without hardly noticing what we've done to ourselves. Our inherently contradictory nature goes largely unnoticed, except I contend that it still deeply influences our behavior and our well-being. I believe that we undermine our best intentions when we fail to notice how our explanations differ from our experiences. We can say that we stepped into the same river twice, but we lose something significant when so characterizing our selves. The self-important might insist that such explanations simply serve as a sort of shorthand and as such do not materially misrepresent experience. I contend that when one extends everyday explanation into the realm of impossibility, we lose something, and something significant.

I'm so deluded that I can become bored when surrounded by difference. I round results up or down to the nearest full number and in so doing, I lose the subtle yet significant ability to see and appreciate infinitesimals. Life's mostly infinitesimals. Blunt too many of those and one might just as well be a robot programmed for mundanity. Everything I see might really be brand spanking new to me, but to acknowledge this, to actually live as if this were the case might well render me at least clinically insane, unable to "properly" interpret objects, seeing novelty in things which really should seem familiar. Our whole society utterly depends upon most of us not seeing what we've never seen before, of not really understanding when we encounter something novel. We must not let its differences prevail, but must see it for just some same-old, same-old again and again.

Life as we know it might well prove practicably impossible should we find ourselves incapable of ignoring Zeno's notions, though we might upon quiet reflection, accept and even understand their wisdom. Their wisdom seems to belong in stories, not in our own experience. Artists might discover this difference and find themselves incapable of resolving it, and find themselves relegated to living in some unheated garret as a result. A painter sees this world in ways unique from how a writer might see it. A sculptor can seemingly see figures imbedded within solids, and even manifest them onto the surface by means of subtraction. The typical cost accountant rarely experiences such visions. I contend that Zeno and his apparent paradoxes serve to better inform those of us attempting to live in the reality we found constructed around us here. Those of us who sometimes struggle to fit in, to find premises for unlocking great mysteries, find ourselves attracted to Zeno'sReality, for he seemed to understand that much never really was what it seemed. It's different.

We, by necessity, it seems, adopt smoothing algorithms, ones which by design produce more predictable outcomes. We must imagine ourselves capable of crossing the same river twice or else why even bother building that bridge? We must materially misrepresent our experience to ever feel as though we share it. Our education, an orientation intended to integrate paradox into a form of logic we live and willingly die by. We sometimes get all tangled up trying to describe how some barber who only shaves those who do not shave themselves ever manages to get himself a shave, but we do not behave as if these knots bother us overmuch. They're like little insults to our intelligence, rarely enough to throw us off. Properly conditioned, we might never notice ourselves incapable of ever stepping into the same river even once.