Me, Myself, and Aye

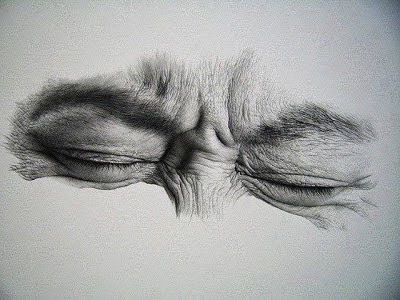

"Nobody becomes invisible

just because they close their eyes."

A pivotal point in my learning how to write came when I stumbled across an arcane little volume at The Library of Congress. In it, the author(s) proposed what I'll characterize as an 'is-less' style of exposition. Since we construct language from metaphors, which must necessarily be fuzzy representations, characterizing anything as being something else makes little sense. Of course the sky isn't blue, it just looks that way. The author(s) counseled a touch more care when characterizing. ©2018 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved

This observation whacked me up the side of my head. For a while, I became hyper-aware of my innocent mischaracterizations and re-edited everything I wrote to avoid is-nesses. My writing became stronger but also less certain. If I could not allow myself to say that so-and-so "is" angry, I might instead report that so-and-so sure seemed angry to me, leaving some benefit of the doubt in place for me and my reader to benefit from. I could be wrong. I became a more fallible but also a more credible witness. I found myself including myself as a tangible presence in my writing rather than simply serving as an off-stage narrator and confident interpreter. Curiously, the result seems much less certain AND more tangible.

I've long reviled the academic writing style that seems to me to overplay the notion that a writer must be invisible. In this style, the writer ideally completely disappears, leaving only Joe Friday facts displayed on the page, in the interest of amplifying objectivity, I guess. This sort of writing exhausts and ultimately bores the toenails off me, like trying to maintain a spirited dialogue with myself or hoodwink at solitaire chess. No matter how hard an author might try to hide behind some ginned-up imaginary third person, the reader still senses their presence. Nobody becomes invisible just because they close their eyes.

If I want to become a writer (writer being one of those eternally becoming, never actually being, sorts of things), I finally concluded that I needed to show up to be present. It couldn't possibly any longer 'do' for me to hoist myself up onto some self-fabricated pedestal and proclaim! I might have to observe instead and own my own perspectives. I could no longer authoritatively speak for anyone else—we, us, them, "everybody"—, but only for me and for myself. I could, without violating this practice, report how The Muse appeared to me, but I could not, describe how The Muse is, was, or most certainly would be. I started using 'seems to me' a lot, in all of its derivatives.

Is-nesses hold the ability to produce what psychologists classify as Derivational Trances, where ambiguity kind of forces the listener to go off searching for what in the heck something means. For most 'the sky is blue' kind of descriptions, which have evolved into meme-like understandability, no search occurs. But when someone insists that "everybody knows", even an incurious brain might initiate a subroutine trying to determine who constitutes "everyone" and how the asserter might possibly know what "everyone knows." Severely careless speech can entrance its listeners, distracting them away from the exchange into nested and looping derivational searching.

My growing sensitivity to the absence of a writer's presence in their work seems to have made fiction more attractive to me than non-fiction. In fiction, the narrator almost always embodies their presence. In so-called non-fiction, I too often find the flat and boring presence only an expert can affect. Whenever anyone insists that something simply is, my head wanders off into the near distance to wonder why. Whether that invisible author insists that the world IS flat or round, I'm pretty certain it's neither, perhaps both. Since flat and round serve as metaphorical characterizations, neither can approach the definitive. Depending upon the observer's perspective, it might well appear to that observer to obviously be one or the other, but never both. It might be best described as both and neither. The observer can easily resolve the controversy by explaining what they see.

Facebook seems overfilled with disembodied people speaking both for and as others, often for collectives who, unrepresented, could never speak for themselves. 'We' has no voice. Neither does 'them.' Someone must assert the authority to speak for these mute entities. I wonder why, which probably undermines whatever message the disembodied author hoped to convey. One of The Muse and my rules for authentic dialogue insists that everyone exclusively 'speak from I.' This means that if I assert something, I'm obligated to own that assertion. I can only authentically speak for myself and for nobody else.

I used to find great safety echoing authority, speaking in the voice of the Royal We. When the Queen insists that "We are not amused," I have grown to understand that she means that she isn't amused. As far as I can tell, The Queen has not graced us with her presence here, so each of us gets to be amused or not. I won't any longer allow myself to cower behind 'We's' voluminous petticoats, no matter how threatening speaking for Me, Myself, and Aye might feel when I hear the roll called.