Optim-eyes

Don Henley

The End Of The Innocence

I listen to the language around me. I listen deeply. I hear insistent preference for The Fairy Tale Form, a descriptive style that might well acknowledge difficulties but also demand resolution, too, almost as if living happily ever after must be the primary purpose of any stumble. We intend this, I suppose, to encourage us. We don’t so much see as optim-eyes, subtly projecting hopes over the top of our fears. This passes as the primary coping strategy of the modern age.

As a consultant, I might have grown to rely too heavily upon the story that I performed transformational work, for I had seen the transformations. But nobody really wants to believe that they might be in need of transformation, for this characterization suggests a certain cluelessness; and admitting to cluelessness carries more taint than a low SAT score. In the modern organization, the appearance of holding knowledge carries more than power, it holds identity.

Whatever the mystery, I’m supposed to know the culprit before agreeing to take the case. The client might not know whodunit, but the consultant’s supposed to know without hinting at the client’s ignorance, without suggesting that he might not know, that he might not ‘be.’ Further, the client will insist upon a right answer, a better response, the very best strategy, optim-eyesed for their success without ever really having any basis upon which to judge what constitutes ‘best.’

This dance creates a positive feedback loop, one which could never really learn anything, reinforced by positive-focused suggestions as if we were three year olds afraid of scaring each other off. We tip-toe through the weed patch, insisting that those are tulips along the way and that we know the way out.

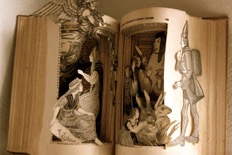

We rarely know the way out of anything, but this humbling acknowledgement won’t buy anyone much. There’s always someone who’s managed to convince him self that he knows, and no shortage of them who quite comfortably set about telling convincing fairy tales to suggestible benefactors; optim-eyesed for mutual delight, at least at first. But worked hard and well, the fantasy might prolong its innocent childhood into adolescence and beyond with additional alluring allegories of dragons, princesses, knights, and wizards chasing ever more promising ever-afters.

Whenever you read a headline saying, “The Five Best Ways To ...”, you can be sure that Hans Christian Andersen and both the Grimm Brothers are spinning in their graves, and equally certain that many good little girls and boys are choosing the pillow they’ll sit on while the yarn’s spun. Invariably, these five best will not have been subjected to anything like rigorous examination, probably emerging more or less as whole cloth as they’ll ever be from the rather lyrical imagination of the author, who, if canny, will cite no more than what everyone already knows, or thinks they do.

A non-fictional counterpart might read, “Five Different (or Interesting, or Confusing, or Anything-Other-Than-Best) Ways ...”. But we are not bred to appreciate mere difference, though even slight differences might counter the positive spin and swirl our glassed-over Optim-eyes anticipate. Difference doesn’t come in sweet undertones, instead favoring savory, sour, tart, and bitter. Our palates seem spoiled from cotton candy characterizations of stone, dirt, blood, and bone.

This story doesn’t guarantee a happy ending. You will not receive a sticker to proudly announce your participation from your sharply-pressed lapel; no continuing education credits offered. This story we engage in as if it mattered, uncertain if it will or if it really could. We do not expect to make a return on this investment. As Peter Block asked, “If you knew the world would end tomorrow, would you plant a tree today?” If you knew for certain that the promised best was a fairy tale, would you still listen to the story?

©2014 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved