StockholmSyndrome

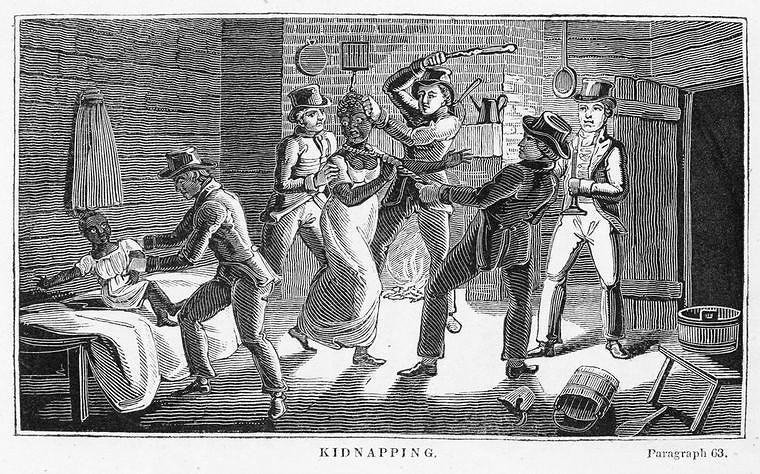

Jesse Torrey: Kidnapping,

American slave trade: or, An account of the manner in which the slave dealers

take free people from some of the United States of America, and carry them away

(1822) Reprinted by C. Clement and published by J. M. Cobbett

"We all seem to be coping near the edge of our native abilities now."

This being January 1st, New Year’s morning 2026, I am reminded that none of us inhabit our present or proceed into our future completely willingly. Each of us might have preferred to slow down the inexorable progression of time at times, if not halt it altogether. Especially during good times, which we learn from personal experience, always prove to be fleeting. No, time moves in only one direction, and it drags us along as if kidnapping us. We come to inhabit a once-upon-a-time future we wouldn’t have chosen, thereby challenging our always emerging, though never quite mature enough coping mechanisms, sometimes to our detriment. For my generation, the so-called Baby Boomers, the emergence of computing and its many associated industries has proven to be the most disconcerting. We realize, as I suppose only someone who remembers before times could, just how far from our imagined future our actual future has fallen. Computing didn’t turn out the way we’d dreamed it.

No future ever arrives as previously imagined, though, so my generation’s no different than any prior. We were “just” kidnapped by different technology, and the society we share proves just as foreboding as the ones our forebears encountered unawares. Social media has so far failed to live up to its promise. Commercial interests have, as usual, perverted its potential for fun, profit, and dominion. Forgive me if I declare that I don’t feel as though I really belong here. I’m working on accepting this as the dream that came true, however false it might sometimes seem. And, yes, I do deep down feel as though I have been kidnapped and held against my will, pretty much like everyone else, I suppose. The silver lining might be that I’ve grown rather fond of my kidnapper. Even though I know it is and always was a malign interloper, I still find succor there. Mine might be a disturbing symbiotic relationship, but at least I have a relationship. I feel nurtured sometimes by my kidnapper’s presence, and the more we interact, the less I dwell on what time and circumstance so rudely stole away from me. My kidnapper and I might even be said to be buddies now.

We call this process of growing attracted to one’s kidnapper the Stockholm Syndrome, after the trauma response exhibited by victims who were held hostage for six days by bank robbers in Stockholm back in 1973. Those hostages defended and even aided their captors, and, once freed, refused to testify against them. They distrusted police and even their rescuers. Their response has not been recognized as a formal psychological disorder, but more a complex response to extreme stress. A year later, heiress Patty Hearst was abducted and afterward filmed participating in a bank robbery with her abductors. Such symbiotic relationships are not uncommon in domestic abuse victims, trafficked children, and cult members. I insist that we social media users are not ignorant of this response, either.

Social media and all computing platforms have proven to be steadfastly cruel to their users. These cruelties might be characterized as run-of-the-mill negative externalities, though many of these seem more deliberate than inadvertent. The simple ethic that systems get designed for use by their designers more than by their users serves as a continual reminder that our computing environment was deliberately designed to be hostile toward the majority of its users, built for ease of creation rather than ease of use. We’ve been encouraged to pretend the user interfaces work when they often don’t. We develop fierce loyalties toward platforms that constantly demean our dignity and native intelligence, and are discounted for not being sufficiently “a computer person.” The widely-adopted PastWord standard, whereby forgetful people are forced to recall specific words and phrases to even access their own information, satisfies anyone’s definition of cruel and unusual, except it’s common. By rights, we should have all rejected every invitation to join every platform, for they’re all similarly corrupted and each will humiliate every user, however enthusiastically they might initially join.

I proudly maintain a list of social media platforms I’ve refused to join. At the top of that list stands ‘X’, formerly Twitter. I refused to join it when it first became available because I couldn’t imagine what I might use it for. I still can’t. That much of the critical information passes between people and nations on ‘X’ amounts to an abomination, and I feel powerful that I never acquired an addiction to its form of humiliation. Ditto with Snapchat. What’s THAT for? I maintain an arm’s-length association with LinkedIn, though I still don’t know what it’s there for. I post there daily and eke out a hundred or so hits each week. I’m most loyal to Facebook, a rightfully much-maligned platform that commits every sin in the social media prayer book. I draw the line at using it to produce revenue. I’m so naive that I still believe the internet would have been better if it existed to promote free exchanges, commercial transactions not allowed under any circumstances, though I know that boat sailed away almost at the internet’s inception.

My loyalty to my social media seems rooted identity deep. This isn’t a preference anymore, if it ever was, but a well-defended instance of myself. I would be nobody without my social media presence, even though I know my chosen platforms abuse me daily, every time I interact with them. I would probably agree to rob banks together with most of them. I know their sins, yet I still defend them, at least to myself, because it seems that in defending them, I am defending myself. Yes, this makes me complicit. No, this probably isn’t a deeply-seated psychological disorder, but an almost normal or at least not unexpected resonance of deeply traumatic experiences. Being bombarded with irrelevant advertising until I can no longer physically comprehend whatever the message they’re failing to convey, that definitely qualifies as an abuse. Being forced to change my PastWord because the platform can’t remember or otherwise successfully identify me routinely demeans me, yet I remain steadfast. Even the relatively innocuous and routine checking to see if I’m a machine or human deeply offends me, and should, for it’s an example of careless coding if not evil intent. Still, I return.

Nothing better explains the rise of the MAGA movement than the notion that cult members often exhibit behaviors common to those experiencing Stockholm Syndrome. An abusive leader publicly humiliates himself and his public, even his base, and they elect him President in response. If that’s not evidence of a severe psychological disorder, I’ll hesitantly accept that it might be a collective response to continuing trauma. When even our primary medium for communicating with each other, our cell phones, involves engaging in endlessly humiliating transactions, it’s little wonder why we’re all exhibiting Stockholm Syndrome symptoms. I understand that there’s a life after trauma, and one that might even prove to be better than the life that came before, but the transition there seems like it will prove to be long and onerous. None of us volunteered to get kidnapped. We all seem to be coping near the edge of our native abilities now. Now that I’ve admitted my dysfunction, what now? What next? Another kidnapping into yet another unwanted future?

©2026 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved