JustWhen

William Michael Harnett: Just Dessert (1891)

"Life most often proceeds by other means than planned."

It might be an immutable law of this universe that JustWhen something seems lined up and ready to go, something else intrudes to blow up whatever best-laid plan was guiding the move. This presence justifies all the encouragement anyone can ever attract. But, regardless of how it feels, these intrusions are never about you. They're just this unsettling property of the universe breaking through at the invariably least convenient times. I know that it seems you get more of these than anybody, but that's a perspective illusion created by you having the only seat situated to see what happens to you but not to anybody else. Ninety percent of these JustWhens are invisible to everyone but the victim.

The occurrence of another JustWhen, no matter how common they seem, does not necessarily render the recipient a victim.

CreepingFormality

Abraham Delfos: Oude man, schrijvend in boek

[Old Man, Writing In Book] (1777)

"I do not yet know how I'll know when I'm finished."

As I prepare a manuscript for publication, I notice a CreepingFormality entering the effort. I began as I begin most things, naive and hope-filled. I will end this effort a little wiser and even a little more knowledgeable: more domesticated. The wild streak that fueled my first steps will have been tamed into a kind of compliance, for certain principles and practices have been replacing my feral enthusiasm with deeper understanding. I've already incorporated my earlier stage discoveries into more consistent practice. No longer simply hunting and pecking, I have been watching myself gain circumspection. No longer merely writing, I'm learning to avoid do-overs. This, despite the sure understanding that one tends to get whatever one attempt to avoid.

I sense a more profound responsibility to my broadening audience as I prepare postings for formal publication.

IncompleteIdiot

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas:

Mounted Jockey (c. 1866)

"Self esteem seems over-rated, if not impossible …"

I find myself somewhere in the middle of the current controversy surrounding Artificial Intelligence. The purists stand steadfastly against it, insisting that resorting to its assistance will, over time, reduce the brightest of us into idiocy. The advocates don't see such threateningly sinister results. They figure AI's just another in a seemingly never-ending line of technology, an indifferent presence and nothing to get all riled up about. I stand somewhere in the middle, as I said, because I sense a clear and present danger of impending idiocy while at the same time figuring the suspected impact has probably been overstated. As my awareness of my own use of AI has increased, I have so far experienced more positive than negative results, though those positive outcomes have come with a price. My AI Grammer Checker, for instance, initially left me feeling like an idiot, for it clearly demonstrated just how little I knew about writing. Now, after a few weeks of continued use, I've come to feel as though I might qualify as an IncompleteIdiot, more like an idiot in training, and that AI has been serving as my teacher.

I had no idea how little I knew about writing before the AI Grammer Checker started parsing my prose.

Swooshing

Peter Sheaf Hersey Newell:

Old Father William Turning a Somersault,

from "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" (c. 1901)

"I might accomplish my Publishing without too much suffering …"

The prospect of a four-and-a-half-hour airplane ride opened up some space I couldn't find while sitting at my desk. I had been unable to locate the space I felt I needed to complete the arduous manuscript assembly process for just one of the titles I'd started assembling when I began this series. I have more than a dozen backlogged. I'd been dutifully chronicling activities I had not actually been doing, but then that tactic seemed typical of my usual approach to anything. I feel the urge to nail down the philosophy of something before fully immersing myself in it. Why should Publishing prove any different? Especially the daunting effort to assemble individual blog posts into manuscript form, an inevitable copy/paste/match-style coma inducer, intricate, supremely dull, and requiring pulling down commands because I cannot decipher their keystroke equivalents: ⌘⌥⌃V, for instance.

I admit I had avoided getting too much into the thick of this effort. It scared me.

'Tweenings

Adriaen Pietersz van de Venne:

Fishing for Souls (1614)

" … always somewhere in between."

I spend most of my days neither here nor there. I tend to transition between one and another state, not quite gone nor quite fully arrived at any particular point in time. My experience here has therefore seemed more of a smear than an occupation, not even my transitions precisely true to any clear standard. I have proven myself fully capable of fooling myself into insisting that I've successfully made transitions and somehow managed to grow up, for instance, even though many cues strongly suggest that I remain in transition. My presence anywhere remains distinctly ambiguous.

My Renewing efforts seem to be ending, or at least The Muse and I will be returning to ordinary time today.

Renewing

Théodore Géricault, after Nicolas Poussin:

Man Clutching a Horse in Water,

after Poussin's "Deluge" (1816)

" … a seemingly new you to see it through."

Renewing seems indistinguishable until after it’s over. During, it might be anything. It runs on intention until it succeeds or fails. One intends to renew, but one never really knows whether one'll be successful until the resulting feeling finally catches up to them. Until then, Renewing can resemble anything, even its opposite.

This underlying feature renders Renewing more similar than different from other intentions.

PrimitiveProgress

Edward Sheriff Curtis:

The Primitive Artist - Paviotso (1924)

"I might scratch a story in a sandstone wall …"

Backward steps can produce forward progress. I tend to get so focused on improvements that I can lose the more primal assurance I can do without all my usual accoutrements. I only really need some of the utensils my kitchen holds, for instance, or a few of the array of pens I keep on my desktop at home. I am not only capable of making do without these tools, but I might also sometimes leave myself feeling better off without them.

It's long been understood that sudden reversals of fortune can produce personal improvement, a sense of freedom curiously lacking when surrounded by the trappings of success.

ARRR&ARRR

John J. A. Murphy: Athletes at Rest (20th Century)

" … they get away with murder …"

The Gospel of Efficiency fails to mention the necessity of Rest and Recuperation. It exclusively focuses on nose-to-the-grindstone dedication, personal sacrifice, of laser-like focus. It calculates using only the sparest arithmetic, not the more complicated calculus of human-powered action. We naturally work in fits and starts, sprints and collapses rather than by more primitive fixed and so-called standard methods. We create by means mysterious, especially to us, so we seem prone to misrepresent our efforts, even to ourselves. We might, for instance, apply fierce dedication when some slacking might better serve. We can insist upon creating by the least creative means, defaulting to mistaking context for something industrial. We're apt to mix our metaphors and garble our messages, then follow our internal directions as if they made sense simply because we created them.

It's not until we catch ourselves slacking that we might notice that something significant must have been lacking from our earlier strategies.

Backgrounded

Agnes Winterbottom Cooney:

Backyard View, Public School in Background,

Rulo, Nebraska (c. 1900)

" … a little embarrassed at my previous blindnesses."

Writing and, lately, Publishing have been my foreground occupations. These occurred within some background, typically unmentioned and perhaps unworthy of mention, for background just is and rarely seems to warrant acknowledgment. We humans are notorious for presenting ourselves as unconnected, as if we were not utterly dependent upon some fairly heavy infrastructure. Each of us belongs to a family which, depending, might or might not warrant mention. We inhabit places, sometimes embarrassing ones, which might seem as if mentioning them would somehow demean us in someone else's eyes, as a small-town rube or a big-city slicker. We conveniently neglect to mention details that might overly complicate how we wish to be perceived by others or even by ourselves. We mostly remain mum on many levels.

But we all understand that we're each imbedded within endless complications.

Marionating

Vincent van Gogh:

Fishing in Spring, the Pont de Clichy (Asnières)

(1887)

" … emergent properties, never properly envisioned …"

Assembling a manuscript feels like puppet work as if I can only accomplish it while suspended by strings and manipulated by a puppeteer. It seems slow and sloppy; each story pulled from its marinating emulsion where it's sat suspended since I first finished it, awaiting a second finish and probably a third. The work seems absurd compared to the hands-on immediacy I experience when writing. Assembling involves no out-of-body trance like writing does. Intuition, enormously satisfying when writing, does not for an instant enter into assembly work. It's measured steps in particular orders, pedantic to a fault, trying. I can't phone in this effort, and I can't for a minute doze through it, for the stories have changed since I set them aside. They disclose new meanings and promise fresh beginnings. Their flavor's changed.

I had been fussing over how long I'd let some stories set before finally assembling them.

Manifestering

William Hogarth, Printmaker:

Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism. A Medley.

(1762)

" … never grant us any deeper understanding."

Publishing exists as an essentially infinite field. From an author's perspective, interacting with it carries all the context markers of any encounter with any infinite, by which I mean that there's no reasoning with it. Any individual interaction holds an essentially random possibility for any outcome: positive, negative, but mostly indifferent. In this way, at least, publishing does not quite qualify as a classic system. I might better describe it as a field and its products as perturbations. Something happens, but whatever occurs was never beforehand predictable. One casts into Publishing without ever knowing what might become of the encounter. One might dream of great good fortune, but there's no guaranteeing any outcome. The best anyone can promise might be an entry, an attractive offering. Whether anyone reads the damned thing, a matter of marketing, by which I mean a matter of credulity, superstition, and fanaticism: mysticism.

Ask any author how he happened to become successful, and the honest ones will answer with complete mystery.

Erratics

William Pether after Joseph Wright of Derby:

Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight

(1769)

" … evidence of history having happened and still present …"

What makes these stories a collected work? What unifying theme do they exhibit? Publishers seem to love to ask authors these sorts of questions, for they seek a discernible purpose for publishing something. One does not properly throw any odd old bunch of pieces together and label them A Work. Consequently, I choose a theme, this series' theme being Publishing, then head out into the wilderness to see what startles up out of the underbrush. I do not work from an outline, which I'm convinced only ever exists in fifth-grade writing teachers' fantasies. I try to keep my wits about me and observe what I do, and these observations become the grist for most of the resulting stories. This series could not exist without the provocation of the overarching theme and my own continuing observing. Still, the resulting series sure does seem awful various from a publisher's perspective, Erratic.

What do I look for when I'm so aimlessly wandering through my writing wilderness?

SwimmingLessons

Fernand Siméon: Gazette du Bon Ton,

1921 - No. 6, Pl. 41:

La leçon de natation /

Costume et chale, pour le bain

[The Swimming Lesson /

Suit and shawl, for the bath] (1921)

"We all engage in SwimmingLessons which we'll never master."

I do not yet consider myself a competent practitioner of whatever it is that I do. I falsely claim to be a writer because I write, not because I consider my writing to demonstrate my competence. I no longer believe that practice might one day render me capable. I engage in a paranoid fashion, not merely as an imposter fearful of discovery, but as if I work on probation, subject to immediate dismissal at the whim of any uncaring overseer. I consider everyone competent to pass judgment on my production, their opinion, their own, and outside my direct influence. I no longer believe that I might one day manage to master my profession, but I will forever aspire to enter journeyman status from apprentice. Rather than practice, I work as if engaging in lessons, SwimmingLessons.

The ocean has never once been conquered.

MetaProcessing

Unknown, after Masaccio: Procession of Figures (1700–1899)

" … mistaking wheel reinvention as some sort of fatal mistake …"

I've long suspected something fishy about process, and not just because of my professional encounters with Process Nazis, those people who could only see their worlds as a series of sequential procedures due to a genetic mutation or something. Modern recipes have no ancient counterpart, for the ancients never managed to become slaves to their routines. Instead, they seemed to have retained the ability to hold their intentions more lightly. As a result, they could only mass-produce a little of anything. Also likely true, they probably lived more satisfying lives as a result.

Now, we inhabit civilizations addicted to our processes.

Bletting

Pieter Withoos: Still Life with Plums, White Plums, Peaches and Medlars (17th century)

" … maturing into final form."

Some fruits require aging beyond their tree to become edible: quince, persimmon, and medlar most prominent among these. Each proves too astringent without further curing, the medlar famous for needing to age right to the edge of rotten before it attains its highly-prized and unique flavor. This curing process, called Bletting, historically occurred in some cool, dark place on straw to cushion the curing fruit. Bletting delays the usual essentially instantaneous fruit-consuming process. Typically, fruit's fate has been immediate consumption once spotted, stored for only very short periods, or preserved, for it usually features a remarkably short shelf life. Some portion of the fruit I purchase ends up in the compost bin because I can't quite keep up with it. It's living while actively dying, and I often lose track of where it’s going until after it's already gone.

The medlar, praised since Roman times, seems especially ancient, for it might need six or even more weeks of Bletting before it comes into its own for consumption, which often involves making a jam or sauce to enhance other flavors, especially wine.

Parallelling

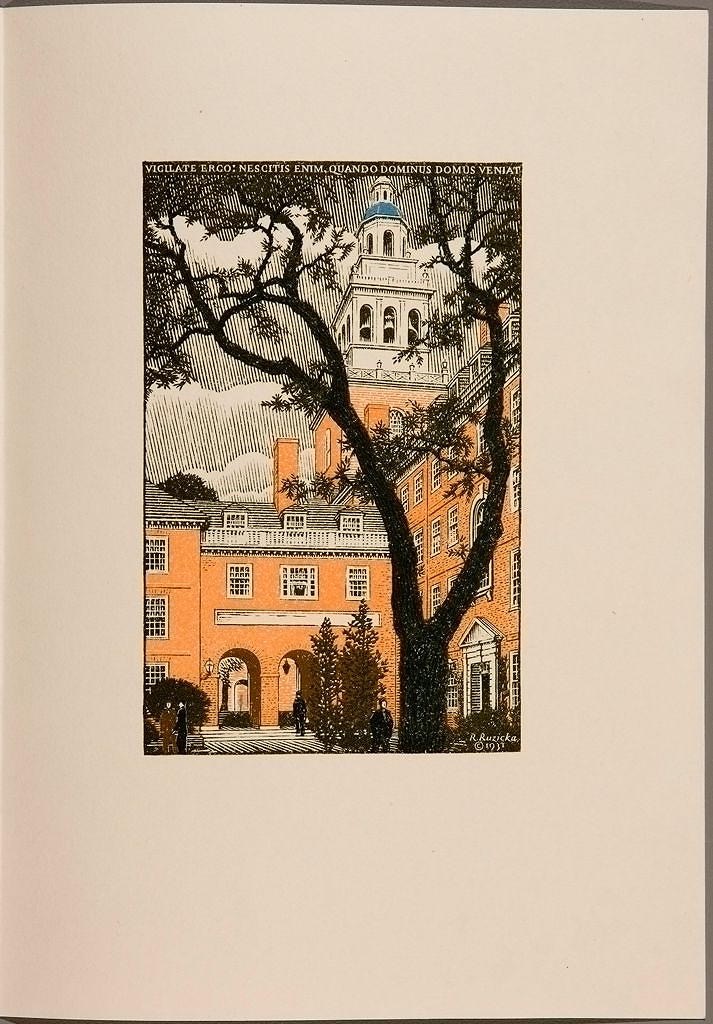

Rudolph Ruzicka:

Lowell House, Harvard University (c. 1931-32)

"My world, like yours, thrives on such intentions."

I maintain and manage a massively parallel publishing system consisting of many disparate parts conceptually connected but otherwise distant from and invisible to each other. I serve as the sole integrating factor, for only I know where the bodies have been buried because I was the one who buried every one. Using this system resembles serial graverobbing, in which my skills must approach master status. The resulting operation stretches the formal definition of system, as all integrated systems must. It was never designed and shows it. Nor has it ever been documented. Instead, it operates via a complex code of local knowledge and rumor. Some pieces barely serve their purpose, but its sole user knows of no better components or, at least, none cheaper. It includes nothing designed or marketed by Microsoft®, for our operator finds their products fundamentally unusable. This means that my publishing system most emphatically does not include MS-Word®, which, as near as I can tell, exists for the sole purpose of rendering writing, and so Publishing, fundamentally impossible.

This story, as every story I've written in this and every other series, simultaneously exists on several supposedly parallel planes.

StrategicHesitation

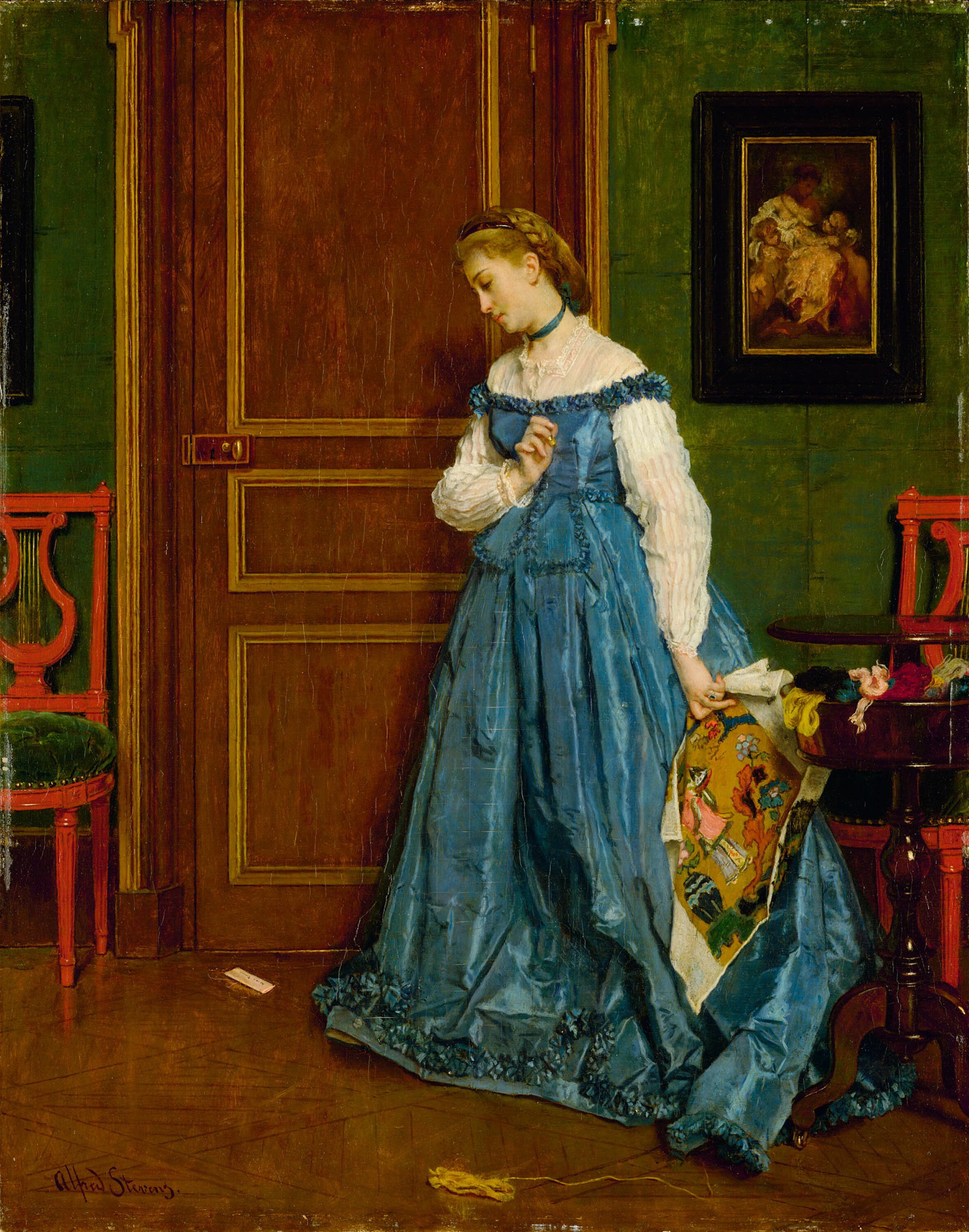

Alfred Stevens: Hesitation [Madame Monteaux?] (c. 1867)

"I might just be playing chicken with myself."

All who hesitate are not necessarily lost. Some certainly must be lost, but many engage strategically, not wanting to waste effort by expending it overenthusiastically and in a naive fashion. Especially immediately after experiencing some fresh revelation, people tend to go off half or even less than half-cocked, exercising freshly-discovered muscles in ways most likely to undermine intention and strain unaccustomed ligaments. I believe it essential then to resist that urge to charge forward holding that newly-discovered sword, lest that nascent swordsman do more damage than good to their cause. The first use of any insight might well best remain a sparing one. It's far too easy to overuse or even abuse unfamiliar forms of magic. It's often best to just use a sprinkle at first.

I have been encountering insights as I've explored Publishing.

KnowingNuthingness

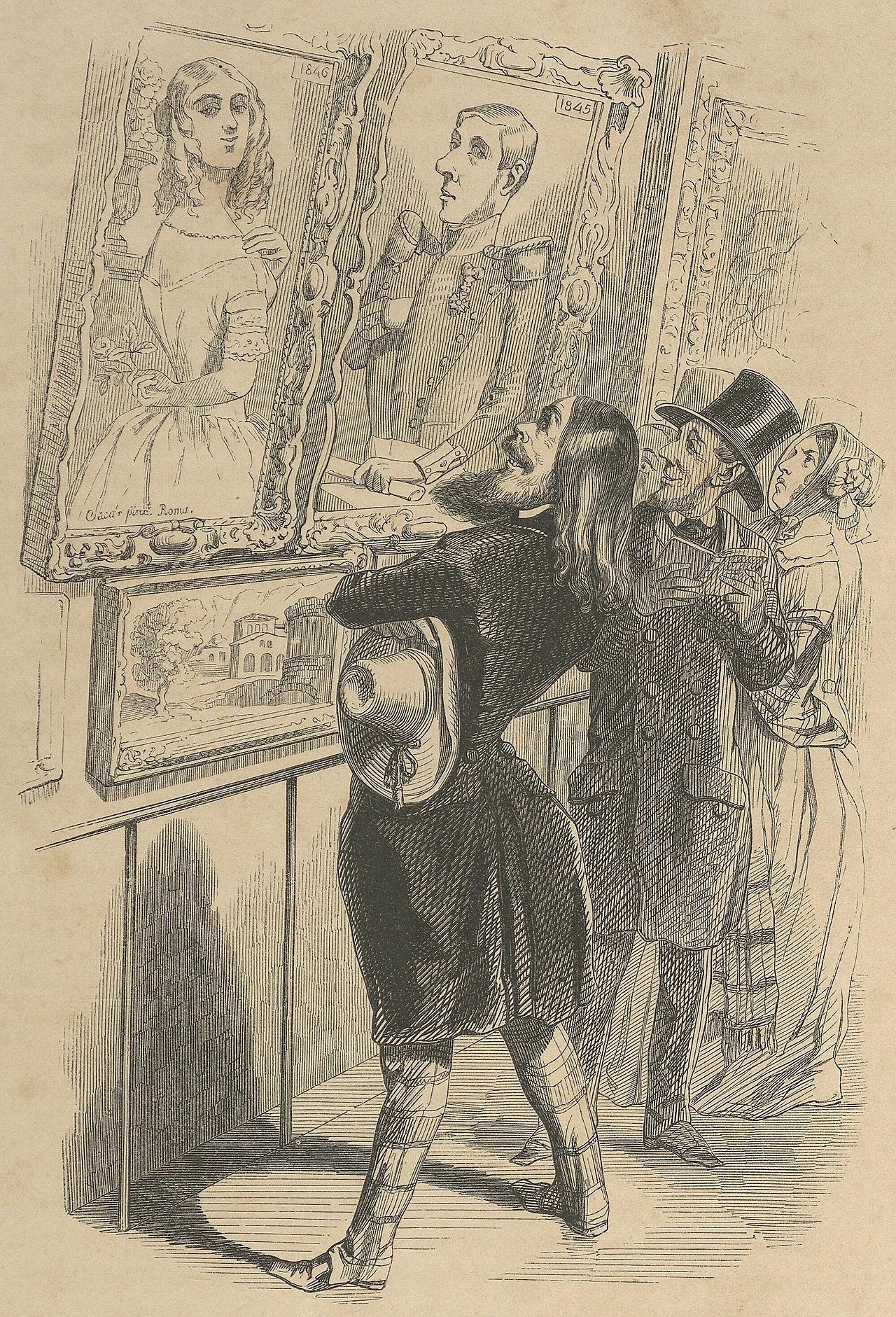

Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville:

Artist admiring his work.

Jerome Paturot a la recherche d'une position sociale

[Jerome Paturot is looking for a social position] 1846

"It's an unfair trade …"

Any profession diligently practiced eventually leads its practitioner back into a state of KnowingNuthingness. Any iteration of knowing action ultimately leads to fracturing understanding. One morning, or one late evening, our protagonist will experience KnowingNuthingness, just as if he was forever before merely faking facility as if he'd never actually known a blesséd thing. He will feel embarrassed recognizing the scores of stories he'd previously and irrevocably published, tales with gross errors embedded within them, each of which quietly disclosed just what an idiot he was, how filled with presumption he had been, how he had been masquerading while probably only successfully deceiving himself. The scales fall from his eyes in that brilliant moment, and he experiences his profession's peak sensation: Nuthingness again. He knows only in that memorable moment that he never knew Nuthing, that all of his passionate strivings had successfully guided him back to zero again. Again!

The wise ones insist that these sorts of experiences benefit the professional.

Homogenizing

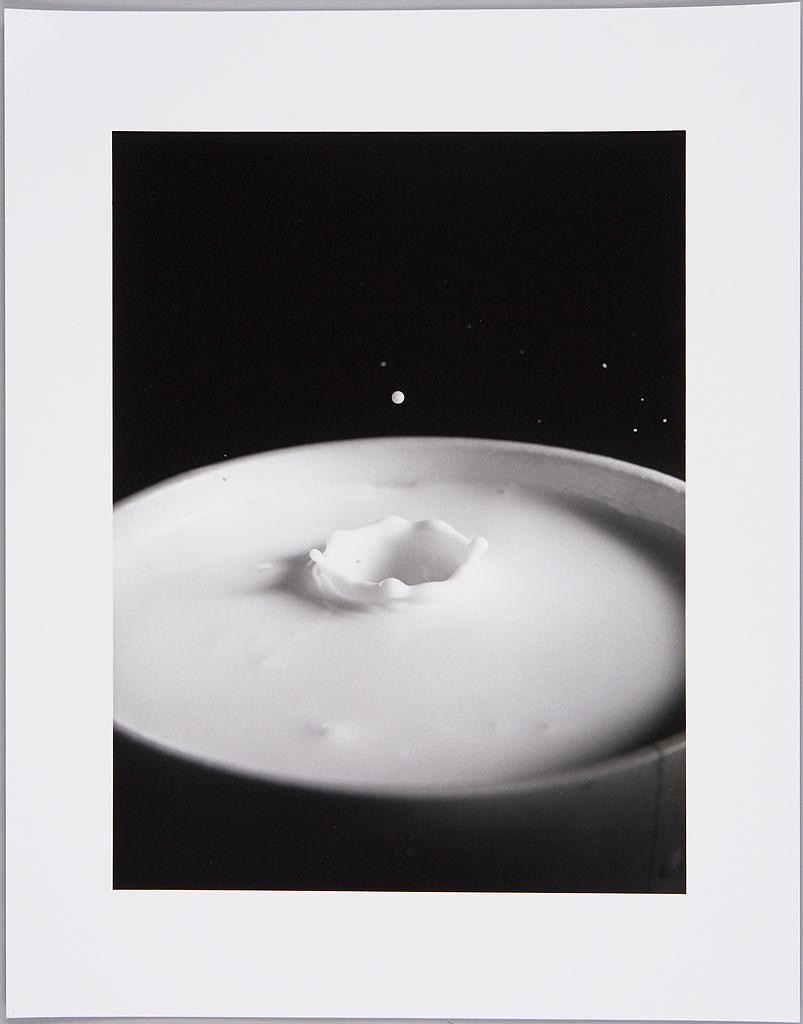

Harold Edgerton: Milk Drop into Cup of Milk (2) (1935)

“ … only become accessible once Homogenized …”

Those final editing passes amount to a kind of Homogenizing of the manuscript. First drafts tend to seem rough and feral in form. When creating, the writer wisely ignored many of the lessons their teachers tried to impart in favor of listening to their small, almost still voices emanating from their heart. Hearts do not know crap about comma placement, however, and no amount of intuition, no matter how damned well-intended, can predict what a Grammar Nazi might insist. It seems helpful to pass the work by Hoyle to gain his perspective, but a writer must never cede creative rights to any rule book. Much that makes a piece of writing interesting comes from its personality, tone, and innate quirkiness. Nobody appreciates a voice victimized by too damned much Homogenizing.

The A-Eye Grammar Engine seems determined to homogenize my writing.

Choreography

Thomas Lord Busby: Billy Waters, a one-legged busker.

Colored engraving from Costumes of the Lower Orders in Paris (1820)

"I build my castle upon shifting sands."

The steps I follow to successfully publish one of my daily stories have multiplied since I started writing this Publishing series. What previously seemed simple became complicated, though my intentions never considered creating anything convoluted. We all understand that this sort of outcome happens, though we remain largely baffled at how an urge to simplify produces complications. The expansion comes in insignificant increments, so-called inch-pebbles, rather than by milestones. An embellishment might require much more work yet produce an effect that seems damned well worth what initially seemed like a small additional effort. Multiply that tweak by twelve or even by five, and the resulting steps become challenging to hold in one's head yet remain too fresh to be easily turned into a checklist.

At some point, what starts as an inspired improvisation becomes an imperative, no longer mere embellishment but an integral part of every performance, not to be omitted.

A-Eye

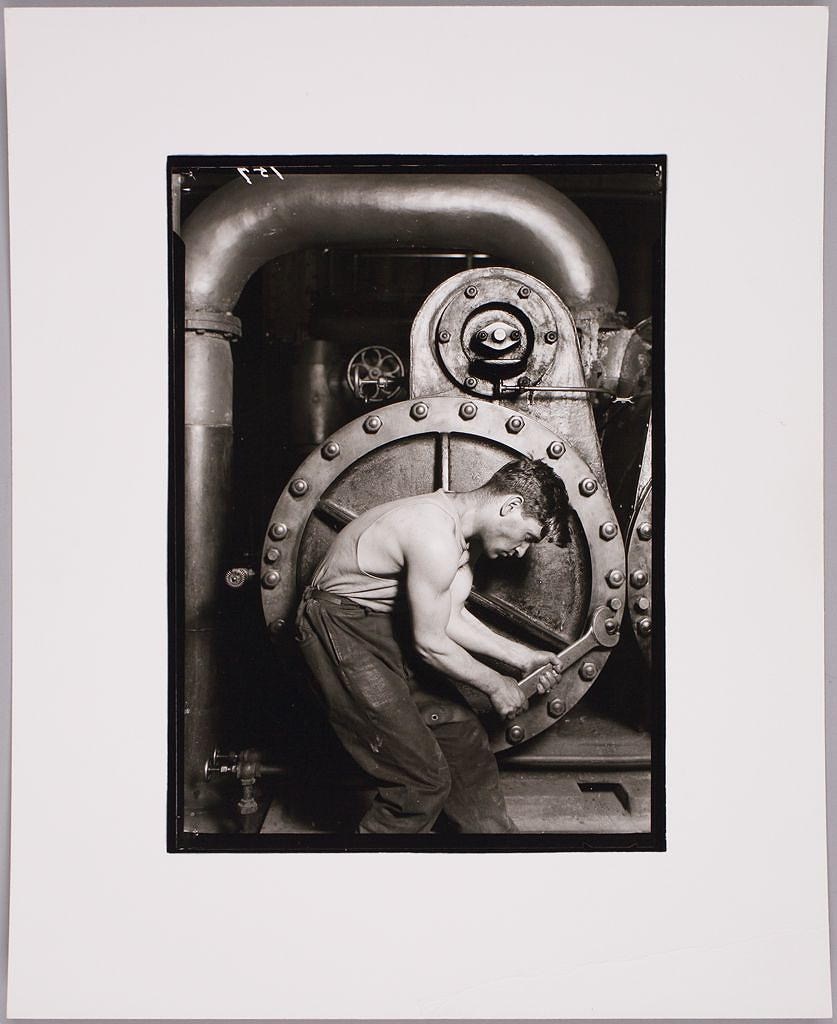

Lewis Wickes Hine: Powerhouse Mechanic (1921)

" … a rather bleak and lonely job …"

I have a confession to make. I sincerely hope that this one will prove to be good for my soul, as I'm reliably informed that confessions tend to be good for the confessor's soul. As with all confessions, this one might involve the disclosure of some sin I've committed or, if not precisely, a sin, some shortcoming. One confesses, I guess, in the sincere hope that one might gain forgiveness, at least from themself and, perhaps, from others. Atonement might or might not be indicated in this situation. I risk ruining my reputation, though, so listen generously, please, understanding that I'm just flesh, more than capable of falling short of any ideal.

I started using AI this week in the form of an Artificially Intelligent copyediting engine.

RabbitHoling

Camille Pissarro: Rabbit Warren at Pontoise (1879)

" … yet still enormously proud."

Final editing seems like preparing a corpse for burial. The body's mass and shape serve as no concern; only appearance matters then. The time for constructive criticism passed long before. The plot's pattern resolved; the author wants only to remember this story as one he finished without regrets. It will always be just as he leaves it now, and the work, on exit, nudges its author into what appear to be warrens, twisting tunnels down surprising holes. The final effort before publishing might as well be labeled RabbitHoling.

The actual finishing work feels remarkably renewing.

PastSins

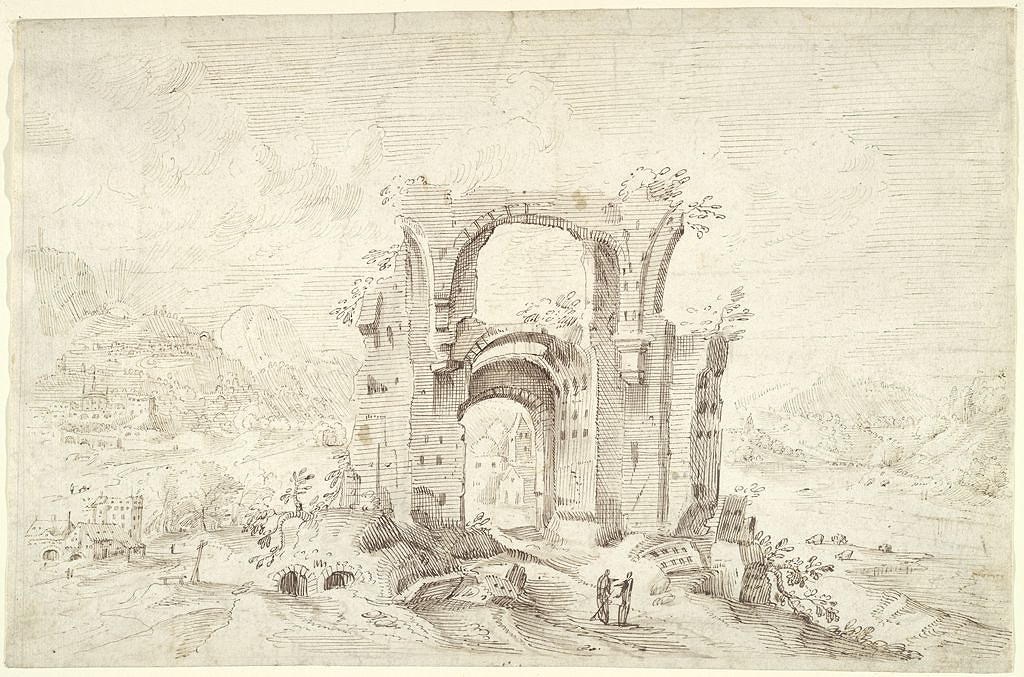

Circle of Hendrick van Cleve III:

Landscape (c. 1525-1589)

"A writer's work never gets done."

Publishing serves as the terminating step in a long series of creations. It works like beatification in that it represents a work's entry into that much-vaunted "state of bliss," whereby it might prove worthy of public veneration. More importantly, it moves out of what I might best describe as a persistent state of sin, for each unpublished work represents some PastSins as yet unforgiven. Writers feel haunted by their collected works which have yet to find publishers. These lay around like haphazardly set aside toys, interrupted before completing their mission. Many of those pieces probably could have never really qualified as more than practice, but they remain undead, never entirely forgotten.

The flotsam surrounding every working writer sometimes (like often) seems overwhelming.

Grooving

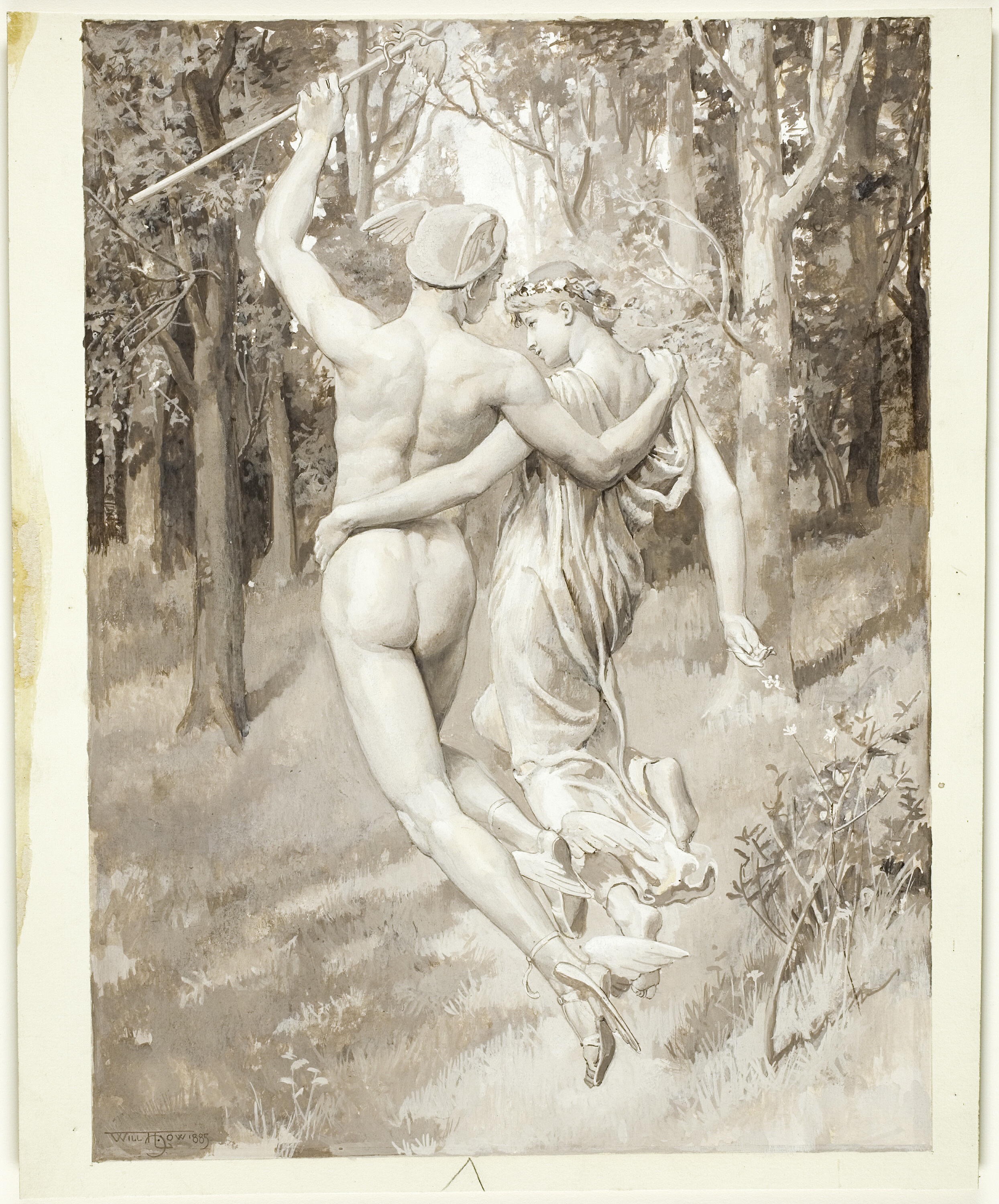

Will Hicock Low:

Into the Green Recessed Woods They Flew (1885)

"The journey, not the arriving, might just be the purpose here after all."

I distrust anyone who seems to know where they're going from any outset, and that goes double for anyone who appears to know very much about how to get there. The first while should properly humble any adventurer as he settles into his somewhat surprising new context. It must be different than expected, or it’s not an adventure. More than half of any excitement comes from the surprise emanating from it. It really should seem different, though judgment had rarely matured to the point yet where very much appreciation accompanies these initiations. They're almost universally experienced as inconveniences, as problems, as broken and needing fixing. Usually and fortunately, by the time the initial disorientation settles down, some fresh Groove emerges from the chaos, and things at least start promising to unfold more smoothly, with no intervention to fix anything really necessary.

My inquiry into Publishing should have proven no different from any standard Class A excursion.

FeedingSystems

Joseph Pennell: Coal Mining Town (19th-20th century)

" … necessary effort …"

Writing works as a relatively self-contained and self-satisfying occupation because it's typically accomplished in near-perfect isolation. Just the writer and his thoughts bleeding out onto the keyboard, a tightly contained system. Publishing adds exponential complexity to writing's simplicity, to the point that writing might seem almost beside any point. The writer leaves the moment to live in anticipation of some future. He writes for an audience then and loses some connection to the familiar small, almost silent voices which had previously guided his hand. He gains the questionable gift of self-awareness, stage presence, and management obligations to engage in FeedingSystems.

That printed page proves insufficient to share and must be duplicated, packaged, and shipped somewhere, somehow, and all that requires systems.

CopyWrongs

Jean Jacques de Boissieu [after Jacob van Ruisdael]:

The Public Scribe (1790)

… tend to default to their Bastard setting unless questioned …"

Publishing exercises what's called copyright, the right to copy. According to common law, copyright belongs to the creator of a work, though that ownership can and often is bargained away in exchange for Publishing. For example, one common precondition to achieve publication involves the creator agreeing to assign their copyright ownership to the work over to the publisher. This transaction has become so widespread now that it's rarely questioned, though other agreements remain possible. For example, some publishers satisfy themselves with First Print Rights, accepting that the author rightfully owns their work in perpetuity but that they might share the work more broadly without making an orphan out of it.

Copyright, in practice, seems a civilizing convention.

UnwieldyMachine

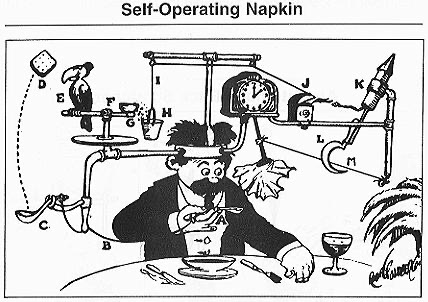

Rube Goldberg:

Professor Butts and the Self-Operating Napkin (1931)

Soup spoon (A) is raised to mouth, pulling string (B) and thereby jerking ladle (C), which throws cracker (D) past toucan (E). Toucan jumps after cracker and perch (F) tilts, upsetting seeds (G) into pail (H). Extra weight in pail pulls cord (I), which opens and ignites lighter (J), setting off skyrocket (K), which causes sickle (L) to cut string (M), allowing pendulum with attached napkin to swing back and forth, thereby wiping chin.

"We're none of us terribly efficient."

My decades of experience with Systems Thinking leaves me incapable of not thinking of Publishing as just another sort of machine, though it seems at best an UnwieldlyMachine. Some devices, though complicated, seem relatively simple. Not so Publishing. I suspect it acquires its apparent unwieldiness from the human effort embedded within it, for Publishing's never accomplished by the mere flick of a switch. Some pieces have been long automated to various degrees. I'm thinking of Gutenberg and his bible printing machines, but even those required excessive amounts of tedious human effort to produce their product. They represented a quantum leap beyond hand-producing illustrated manuscripts, but they remained tedious as, indeed, has the overall Publishing "system" to this day.

Its necessary mindfulness helps render it Unwieldy, for mindfulness takes time when the whole purpose of systems seems focused upon trimming time from production.