SayingNothing

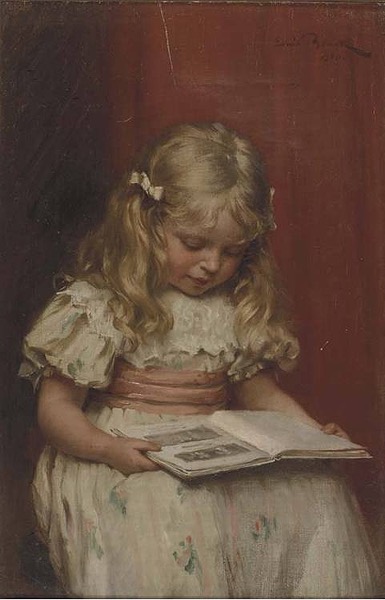

Emil Brack: The Picture Book (1900)

"We must have said everything worth saying … "

They say that there's no fixing stupid, but I believe that smart often proves even less fixable. There's never any real advantage for being the smartest person in the room, for instance, because everyone else will struggle to comprehend what the smarter one's getting on about. Out thinking others earns few appreciations, and that sort of reputation can leave one carrying disadvantaging expectations. Many will sit watchful, waiting for the so-called smart one to embarrass himself with seemingly irrelevant insights. Further, the really smart ones often find that their best contributions come from SayingNothing, from squelching their brilliance lest others find it off-putting. I confess that I don't know any of this from personal experience, since I'm rarely accused of personal brilliance, but I've noticed and I've known some smart people who didn't mind confessing their sins and shortcomings.

I once had a daughter whose story I might submit as prima facie evidence in my case. She died yesterday at the age of thirty eight, untimely, after a lifetime struggling to fit in. Back in grade school, she became the usual suspect because she'd usually speak up when she thought she knew better, which she usually did. She earned a streak of visits to the principal's office for what I considered tiny infractions, like that time when her teacher invited his students to speak up if they had any suggestions for improving his classroom instruction. She had a few, took careful aim, and unloaded both barrels. The principal seemed particularly discouraged by that episode. We enrolled her in a different school, where she suddenly flourished. We took her to a child psychologist for evaluation and his finding seemed fairly straightforward. He declared her the smartest person in the room, a diagnosis that only served to validate the problem, which of course was not really a problem, but a feature.

A feature of the rest of the rest of her life. She played a few moves ahead of even grand masters, some of whom became thin-skinned when perceiving a threat to their dominion. My daughter continually struggled to fit in, often exhibiting disconcerting degrees of competence when engaging. She struggled with muffling her brilliance, with maintaining her station. She found frustrating the rules of civil engagement, where propriety insisted upon SayingNothing when almost everything ached for mentioning. Who would ever understand? Would anyone ever understand? She wrote. A published author at thirteen. A perennial poet. A translator and editor of note. She spoke Spanish in several dialects and maintained clients who insisted that she perform all their public translations. She once simultaneously translated a Nobel laureate's speech. She'd mastered remote learning a decade before the pandemic rendered it mandatory. She found a husband worthy of her who deeply appreciated her presence. I believe that she became the greatest mystery to herself.

She lived her life in words, struggling most with SayingNothing, an effort at which she utterly failed. Her words seem to have prevailed as we both suspected they always would. Even her fresh absence says something, leaving me and The Muse speechless and numb. She chose her exit and I respect her enough to question questioning her judgement. I wanted different as did her whole extended family, maybe even especially me, her dad. We spoke of many things while SayingNothing. We must have said everything worth saying, for now we're permanently SayingNothing. She wrote me a Christmas poem last year. It said everything.

For Dad

You knew the world was wide and open

Before you spread your hand

Wide and open like that world of yours

Placing it in mine

-Heidi Astrid

©2021 by David A. Schmaltz - all rights reserved