Spark

Jan Collaert: New Inventions of Modern Times [Nova Reperta],

The Invention of Book Printing, plate 4

(ca. 1600)

"If I can stay in the game and somehow retain my patience, insight eventually visits …"

When I started this Authoring series two full months ago, I suspected that success would require some fundamental understanding to emerge, though I didn't at the time understand just what that understanding might entail. Authoring involves wrestling with so many simultaneous mysteries that they prove impossible to inventory. It seemed that at least one question was hounding me each morning. Through early days, I found it convenient to just let the mysteries be. Later, the unresolved ones seemed to slow then stall my sense of forward progress. I felt tempted to just put my head down and bull through those barriers even though I knew, or believed I knew, that these were the sorts of barriers that nobody ever successfully bulls their way through. I suspected that something would happen, some seriously uncertain something, which would transform the series and at least contribute to turning the resulting book into something more than mere writing, into Authoring.

Many things just seem to require patience.

Paradigming

Giorgio de Chirico: The Painter’s Family (1926)

" … from his future turned dystopian on him, he might caution others to be wary …"

I want to have written a book of unique form rather than just another copy cat derivative work. All books seem very much alike in that they feature a number of pages tucked between covers, called "boards" in the trade, but the old adage that you can't tell a book by its cover also holds true for a book's form. A book is not simply a book in that it also holds the potential to transcend what the term book meant before this one came along. Forever after, history will be divided into two components, before this book and after this book. That book's the one, if I'm honest with myself and with my readers, I want to have written, to be writing. I want to believe that's the book I'm presently creating and also the book I have up in manuscript galleys awaiting publication, a great treasure awaiting discovery. A part of me, the rational, more-or-less sane part, understands that this future probably does not stand before me, yet my hope still springs eternal. The result seems to be a generic Want To, Have To, but Can't Dilemma, in no way exceptional, for it might well be that everybody, every writer, painter, chef, and teacher aspires for just this sort of impact and also that it cannot ever be engineered, no matter what. There are good reasons for this to be the case.

First, such Paradigming can only occur after the fact.

TimeShifting

Thomas P. Anshutz: The Tanagra (1909)

"Best if nobody can peek into the workshop while Geppetto's carving."

I write in the wee hours. Everything else in my life, including Authoring, comes after my writing's finished. I try to interface with everyone else's world, but I insist upon at least my writing time each morning, and that sometimes sloughs over. It seems important that my writing occurs early in the morning, under the cover of darkness into dawn. By dawn, I'm almost always finished, cleaning up the mess I always make, completing my final edits, Proofing one or two more times. By seven, I'm free to start thinking about breakfast and to get myself suited up for my day, though the last two years have found me largely suiting up to go nowhere given the Damned Pandemic restrictions, which have suited my lifestyle just fine. By the time The Muse wakes up, I've already put in four or five hours. I live that far ahead of her, I imagine. I'm TimeShifting.

We eat supper together, which might be the only time we see each other all day.

Authdacity

Marcel Duchamp: Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2

[French: Nu descendant un escalier n° 2] (1912)

"To do it properly means that you must seem to be doing it all wrong …"

The Muse engages in project work, which has always been a curious offshoot of what I might call regular work. Project work seems strange because its primary purpose seems to be to do away with itself. A successful project will work itself out of existence, which seems like an odd foundation upon which to build a career. Further, most professions prescribe practices common to all practitioners. Sure, a few outliers always exist, but the mainstream engage with remarkable consistency, so it shouldn't be surprising if project practitioners, too, usually attempt to adhere to a few widely-acknowledged blessed practices. The Project Management Institute even publishes and maintains what they refer to as a Body of Knowledge, an encyclopedic collection of practices they've blessed for broad application. For an engineering project, these practices might generally work, but project work, being unique, often requires some differences in how one engages. The Muse, for instance, often engages in scientific projects, ones intending to discover something. One does not plan, control, or track a scientific engagement as if it were an engineering assembly effort. Or, I should say, that one shouldn't plan, track, or control a scientific engagement that way. Most try to. The Muse doesn't, wherein lies her mastery. She appears to do it wrong.

I'm learning that Authoring, too, seems to demand some different sorts of management than does other kinds of engagement.

BigChicken

Melchior de Hondecoeter: A Cock and Two Hens, with Chicks, in a Landscape Setting (1656-95)

"A BigChicken will swallow anything."

My face mask might successfully cloak from the usual observer the fact that I'm a BigChicken. Pin feathers successfully tucked in beneath an over-sized N95, and anyone might mistake me for a man. Inside, behind that mask, lies a deep truth and a continual embarrassment. I tend to move forward by first crouching behind. I will not lift up my head to survey the territory before me for the longest time, choosing to nurture terrifying fantasies rather than getting to the normal business of slaying dragons. I am evidently not brave. Oh, I've accomplished plenty in my time, but not nearly as much as I've fled from or declined engagement with. I first imagine failing, and failing big, before getting over it and proceeding.

What courage I do exhibit tends to be of the counter phobic kind.

Systemantics

Peter Paul Rubens: The Incarnation as Fulfillment of All the Prophecies (1628-29)

" … without having yet achieved any maturity."

My Authoring efforts amount to nothing more than my attempts to master another system. An old systems thinking adage insists that learning one system provides insight into all systems, and having learned many systems in my time, adding Authoring to my vitae should not prove utterly impossible, and yet some days it seems as if Authoring might prove special by proving itself utterly impossible to master. The systems thinkers have this contingency covered, too, for as John Gall, system thinker and author of the sadly entertaining Systemantics- How Systems Work and Especially How They Fail (General Systemantics Press: 1975/78, 1986, 2002), all systems are not only part of larger systems but also comprised of many smaller systems, each of which is infinitely complex. Nested infinite complexity explains a lot of what I see when interacting with and attempting to master Authoring, and also what I experience when attempting to interact with even the more mature systems in my life, the ones I might naively expect to perform predictably.

Last week, I pulled into my pharmacy's "drive thru" window, responding to an automated voice message which alerted me to prescription refills ready for me to fetch.

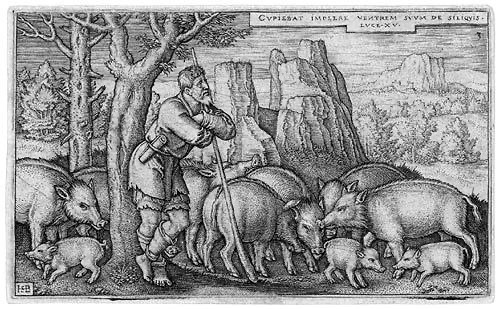

Backsliding

Hans Sebald Beham: Engraving of the Prodigal Son as a Swineherd (1538)

"Backsliding into my future."

After three weeks of steadily improving Spring-like weather, the temperature started falling yesterday and has plummeted down to twenty degrees Fahrenheit (-7C) this morning, with light snow. I spent a rough half hour this morning finally managing to get past LinkedIn's login gauntlet, failing a half dozen times before mysteriously being allowed in, only then to wonder why I'd bothered. I found messages from three years ago and even older, from before I'd last lost the questionable ability to log into that world. I found an essentially infinite queue of long unanswered messages and no evidence of anything resembling my much-touted network, along with what's still the most bafflingly opaque user interface in an industry where bafflingly opaque user interfaces remain the standard. I still can't tell what LinkedIn does, what it's for, it's purpose. The universe seems to be reminding me this morning that progress, once General Electric's "Most Important Product," does not now nor has it ever moved exclusively forward. Once the very epitome of conglomeration, GE has lately been divesting, retrenching back into once core businesses. Progress was ever thus. Even rivers, if one can quiet their mind long enough to observe rather than project what they see, will exhibit prominent backeddies and backwashes along with what we generally perceive as exclusively forward motion. Progress, seen as it actually manifests, proves confusing, a complicated calculus.

And so it probably should be for Authoring, too. It's both Chutes as well as Ladders out here on the cutting edge.

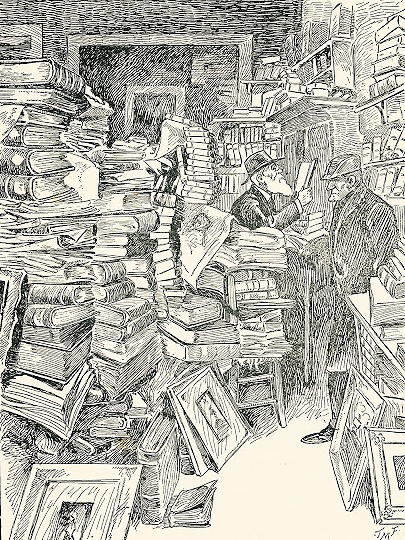

BookSale

Thomas Fleming: Inside the Old Curiosity Shop. Source: Around The Capital with Uncle Hank (1902)

"I wonder what it might have felt like to live in those days …"

The boxes sit everywhere around this town, in front of shops and stores, clearly marked as present for donations to a BookSale. The local chapter of the AAUW (American Association of University Women) sponsors this annual event as its primary fund raiser. For a weekend, they take over a large conference room at the best hotel in town and fill it with donated books, sorted by general topic and kind, and commence to selling them. This always proves to be well attended. Who wouldn't want to browse through piles of musty books on a February weekend?

The inventory includes all of the usual suspects.

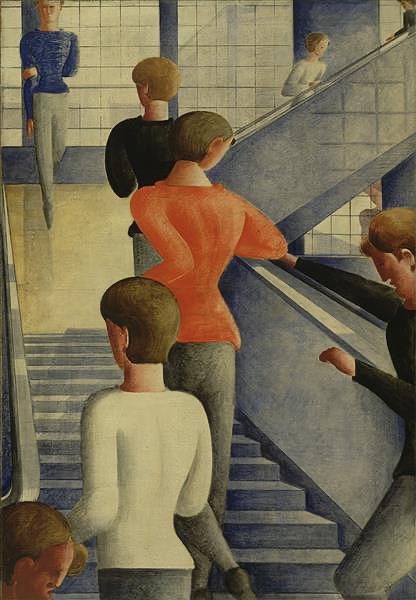

Avant

Oskar Schlemmer: Bauhaus Stairway (1932)

" … wisdom can only come after already expending altogether too much time and energy and effort overthinking these questions."

I don't usually identify myself as an Avant guarde writer, but I've been rethinking that notion since The Muse introduced me to a woman who advertises herself as an Avant Gardener. In most ways, I suppose, she's a traditionalist, but she brings a twist to her focus. Sure, she can spout off Latin plant names, but she imagines them in unusual combinations, in places where no traditionalist would ever consider placing them. In this respect, then, she fully qualifies as an Avant designer, Avant meaning 'combining forms.' In a similar way, I guess, I might qualify as an Avant writer, since, I, too, combine forms to produce a unique result. Reading one of my manuscripts produces different sensations for me than does reading others' work. I thought the differences mere quirks at first and found myself rather embarrassed by them. As I've reflected upon my experience, though, I see a sort of signature emerging. This must be emblematic of David's writing, how he does it. It's not precisely wrong, but different. Whether it produces pleasing sensations might be a different question.

One should always question how to judge the quality of any Avant creation, for comparing it should properly prove problematic.

Detritus

Winslow Homer: Sharks; also The Derelict (1885)

"I can please The Muse by finally getting around to cleaning up the last of last season's mess …"

When we replaced five large picture windows last Fall, we created Detritus. We leaned the old glass up against the fence at the back of the formal rose garden, almost out of sight and definitely out of mind. I'd asked our carpenter's wife and business partner if she knew how to advertise the panes on Facebook or somewhere and she said that she'd take care of it. Sure enough, a week or so later, she texted me to report that she'd found an interested party. I'd not seen her text until a couple of days after she'd sent it and the deal never closed. Winter passed with that glass placidly leaning, bothering nobody. Imagine my surprise when I received a message yesterday afternoon that just said, "Almost to town. Where can we meet up about the glass?" Athena send a follow-up text a few minutes later reporting that the glass guy was finally coming to collect his prize. This news delighted me because the glass had become one of the few remaining bits of Detritus from The Great Refurbish, which we'd almost finished two months ago.

I'm still learning that trying to accomplish anything produces encumbrances to further forward progress, also known as Detritus.

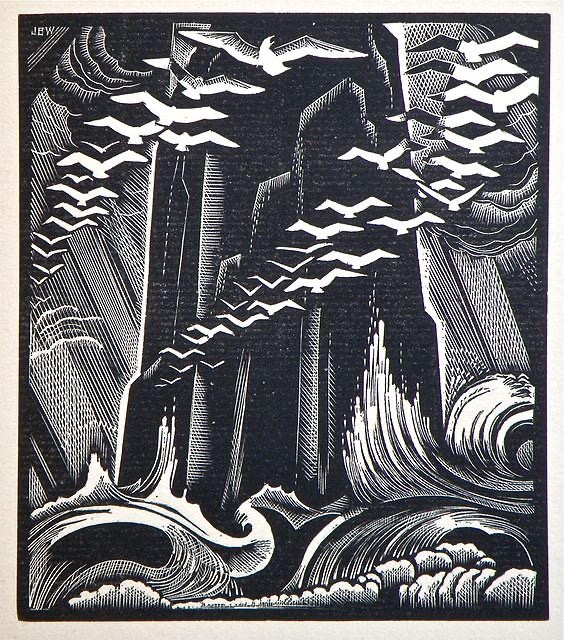

Breakthrough1.0

John Buckland Wright, Freedom (1933)

"Perhaps it was never the problem we convinced ourselves it was."

Today's Authoring Story presents a Breakthrough, what I'll label Breakthrough1.0 in recognition of the high likelihood that this will prove to be the first one of, if not many, then a few upcoming Breakthroughs. They do tend to come in manys following some stuckness. One Breakthrough begets others. A snowball might spawn an avalanche. I realize that this one might well seem out of context, because it's not about Authoring so much as a product of Authoring effort. I'd grown dissatisfied with what I'd earlier written as the preface for my Cluelessness book, the one I've been preparing for publication as part of this Authoring work. What follows serves as a second draft of that preface. I present it without further comment and humbly request that you, dear reader, savage it if you can. This preface, of course, being intended for a book entitled Cluelessness, should exhibit some Cluelessness itself. I wonder if it's understandable, compelling, or seemingly stumbling all over itself? Have at it, please. I promise to be grateful.

———

What sort of person writes a book titled Cluelessness?

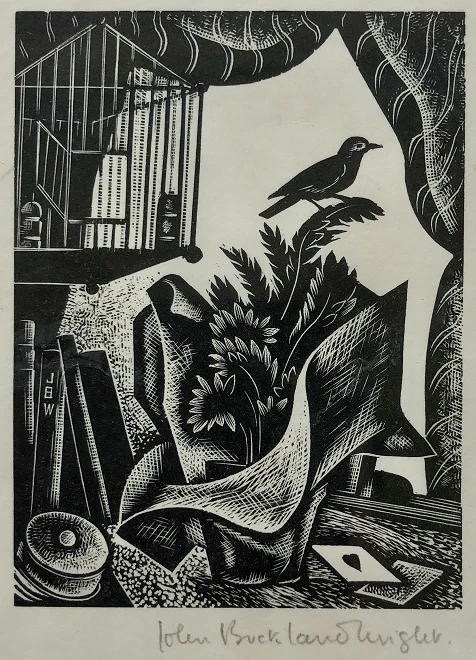

Slip over here for more ...Dolt-Drums

John Buckland Wright: Title Unknown (date unknown)

" … willing to tolerate anything to end up somewhere else."

A point comes, usually somewhere in the middle more than near the beginning or end, where I lose my way. Whatever forward momentum my original bright idea imparted has, by then, largely dissipated. The objective's attraction, however initially strange or alluring, loses its magnetism and I feel adrift amid considerable flotsam: the odd oar, a life jacket, a leaky ice chest, and an almost refinished manuscript. I've forgotten what I was supposed to be up to. I've lost the vision. Once steady trade winds betray me and my rigging slaps impotently against mast and spar, luffing. So recently filled with inspiration, I feel struck stupid. I lose my course and my purpose. What the ancient mariner referred to as the doldrums, the horse latitude stall, I might just as well call the Dolt-Drums. I'm struck by just how dumb I seem.

What was I thinking? What was I feeling? What, again, did I firmly believe I was pursuing?

ChangingVenue

Lucian Freud: Reflection with Two Children [Self-portrait] (1965)

" … my perspective suddenly vaster"

This Damned Pandemic has severely limited my mobility. As a writer, I treasure the movability of my craft. I can just as easily write in the backyard gazebo as at my desk. For years, my desk served as the last place where I'd consider tucking into any actual work. Since the shutdown started two years ago, though, my desk has served as, well, my desk. The view overlooking the center of the universe, where we moved my desk eleven months ago, and The Grand Refurbish, finished two short months ago, improved my location if not my variety, for before the sequestering, I maintained a hot half dozen regular alternative places to work. I could just drop in either of a couple of Starbucks or a local coffee shop near the university, or even another up in our mountain village. I could choose from two fine libraries or a breakfast place with outside seating on Main Street. If I felt constrained at home, I could just head out to find some properly bounded isolation my writing seemed to thrive upon. No longer.

With the COVID and her variants, I hardly ever leave the house, let alone go sit in any of my used-to-be usual public places.

Enhollowing

Theo van Doesburg: Neo-Plasticism: Composition VII [The Three Graces] (1917)

" … my bane as well as my refuge."

My daily Authoring essays have become something of status updates, a widely-abused and misunderstood art form. Back when I managed projects, I thrived or suffocated on the quality of my status reports, so much so that I might have spent the bulk of my time strolling around, visiting with project community members, gathering their impressions of where we were, where our project might be located in space and time. These were Blind Men and the Elephant excursions where each witness testified to often wildly different perspectives. One might be way ahead of where the schedule predicted where they'd be while others reported falling further behind. My job was seemingly to cobble together all these divergent perspectives to report where the effort really sat. These reports were, as a rule, works of fiction intended to keep the sponsoring and managing authorities out of the project's underpants so that we might continue working. Too much of a scent of trouble might incite an inquisition, a review featuring Fundamentally Unanswerable Questions and project managers like me, chartered to provide reassuring answers. Few events were ever more disruptive than helpful inquisitions.

Senior management would issue their own reassurances following the review so that things might return to their smooth-appearing operation again.

Inging

Flag of Qing dynasty or Manchu dynasty

"It might be that I'll be no different after."

What am I doing? Sitting. Breathing. Thinking. Being. Authoring. Inging. Not just any one of these activities, some of which actually involve movement, but simultaneously all of them. What am I, then? Sitter? Breather? Thinker? Be-er? Author? Ing-er? It seems that I'm most likely an Ing-er. I -ing, and therefore I am. Whatever I'm doing, I'm Inging. Right now, I am writing, but not just writing. At what point did I earn my creds as a writer? I know for certain that under no circumstances will I ever only write, for I must also sit, breath, think, be, author, while also Ing on several concurrent levels. Maybe I'm a perpetual part-timer.

I ask these silly seeming questions because they don't necessarily seem all that silly to me.

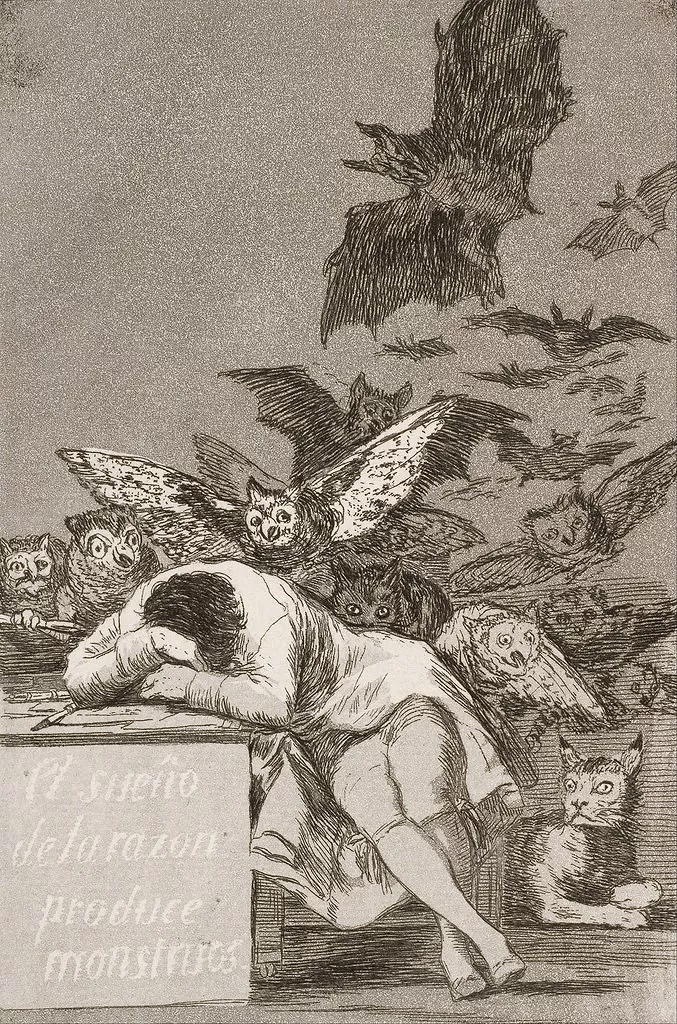

StalkingDream

Francisco de Goya: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,

No. 43 from Los Caprichos [The Caprices] (1796-17980)

"Authors of their own meanings …"

My friend Lynn Kincanon writes at least a poem every day. She writes good ones, too, ones not too full of flowery allusion and not so superficial that they don't inspire. I think of her as an every day poet, profound and subtle, accessible and good, often great. She was one year named the poet laureate of Loveland, Colorado, and enjoys a decent Facebook following. Go friend her there. You'll never regret that you did. I introduce you to each other—Lynn, PureSchmaltz member, PureSchmaltz member, Lynn—because today's Authoring story was inspired by something Lynn wrote in the last week or so. She spoke of StalkingDreams, of dreams that seem to come to her on the installment plan, visiting in odd succession, refusing to resolve. They might become close friends, familiar as family, however otherwise unsettling they might remain. It's as if these dreams were movies from an only almost parallel universe, just a touch orthogonal but almost plumb. They're damned persistent, consistently presenting key metaphors and allegories as if insisting that we come to understand their deepest meaning, as if their story really mattered.

I've hosted just such a dream for innumerable sessions over recent seasons, not just a few nights running, but months and quarters.

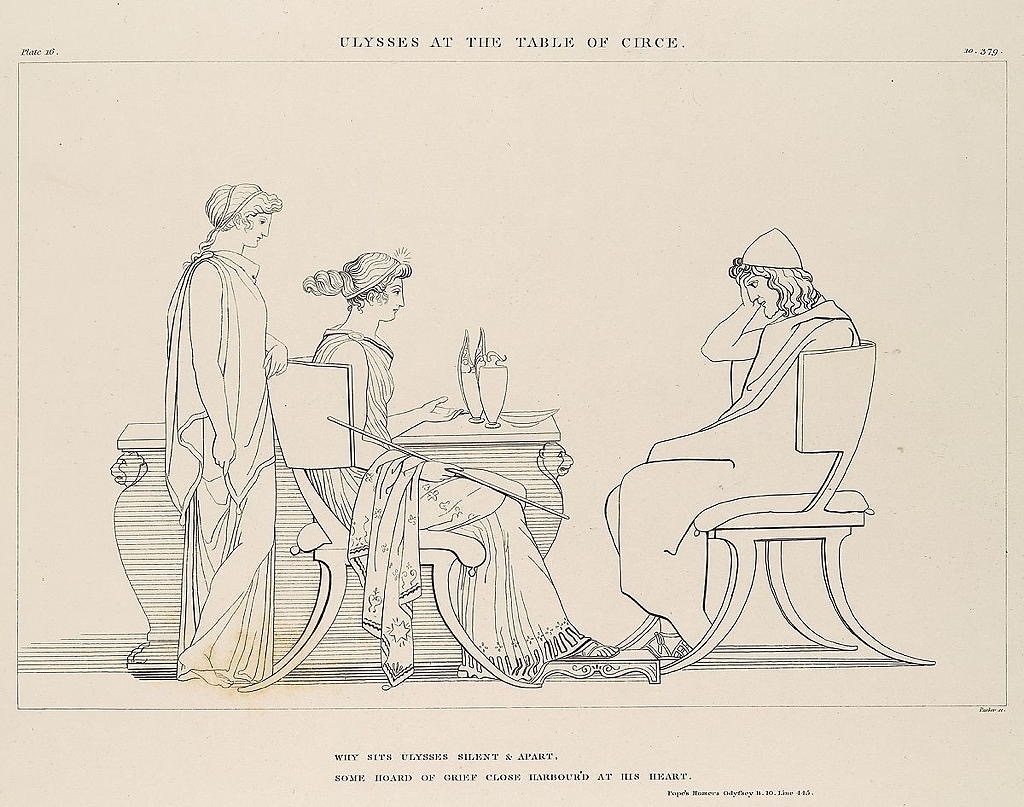

TheNarrative

After John Flaxman: Ulysses at the Table of Circe

[The Odyssey of Homer] (1805)

"Discovering it's a dance."

For most of history, people believed that an actual Homer, author of The Odyssey, existed. In the nineteen twenties, a young anthropologist made a shocking declaration. He claimed to have determined that Homer was most probably a role and not an actual individual historical figure. He based his assertion on observation. He visited Macedonia and listened to traditional tavern singers, who specialized in singing lengthy epic poems, often hours long. He learned that these singers could repeat these poems verbatim, night after night, with virtually no variation, a seemingly inhuman capability, yet each such singer managed it, even when in his cups. This narrative first received much push-back from the field, but over time, the simple logic of the story seemed to supplant the centuries of alternative explanation. It was eventually much easier to believe that generations of storytellers developed and preserved these stories over eons rather than that a single individual lived and chronicled them in a single generation. The story about the story changed.

A fair part of Authoring has nothing to do with the physical manuscript, the apparent story in question, but the story about that story.

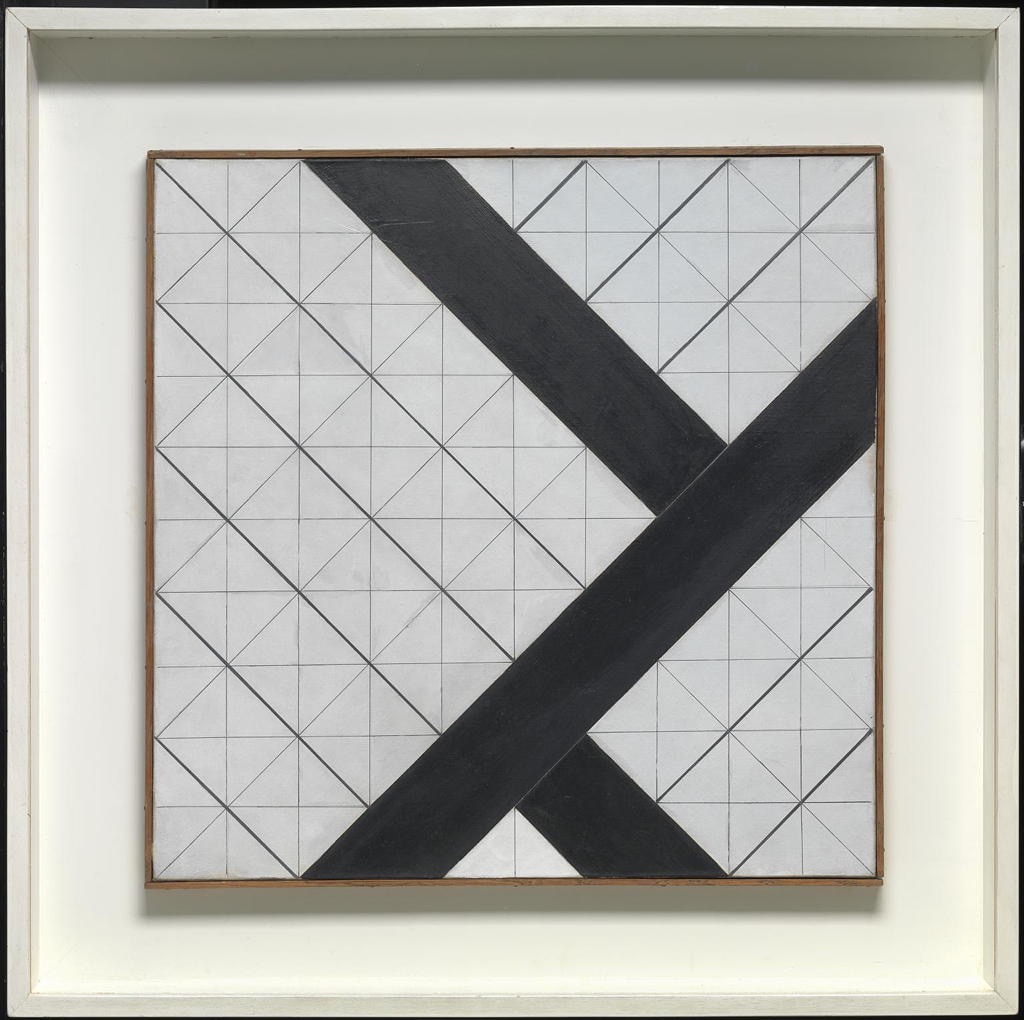

GoodAdvice

Theo van Doesburg: Counter-Composition VI (1925)

"I might ask if another wants the benefit of my experience."

The best advice I ever received arrived just after my friend WayneeBoy asked me if I wanted some advice. He had not begged the question, either. He made an honest offer. If I had not nodded my approval, he would have held his advice to himself, none the poorer, for his advice came on multiple levels. The first bit he communicated by observing an uncommon courtesy, similar to that extended whenever a visiting sailor seeks to board another's vessel. "Permission to come aboard, sir?" Boarding a ship without first asking permission could cause an international incident, so by long tradition, permission gets asked and extended, a small courtesy which somehow seems to sanctify the visit. We, as in you and me and almost everybody, commonly neglect to ask permission to dispense our GoodAdvice before dishing it out. We often sow our seeds without first preparing the soil, without first considering whether the one so obviously needing our GoodAdvice might be in any position to hear, let alone act upon it. We tend, then, to waste an awful lot of effort.

I know that it seems, in that pregnant moment, that I might be able to help another avoid an error or perhaps recover more easily, if only, if only. If only, indeed!

Slideways

El Greco, View of Toledo, c. 1596–1600

"I'm sliding Slideways …"

How might I describe my writing? Probably not in the same fashion that I usually write, for a description seems of a different order than an observation or worse, an inference. It seems one thing to state that the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog and quite another to explain why. The explanation seems necessary because who could possibly conclude the intention without some sideways explanation, one posed at a slightly higher and sideways orientation, perhaps looking down upon the commotion? I'd say that no one's very likely to jump to an accurate interpretation without some outside orientation, without the author of the expression disclosing his intentions, whether those seem at all transparent or even present in his silly sentence. Explaining that the sentence in question serves as an English-language pangram—a sentence that contains all of the letters of the English alphabet—the deeper meaning comes clear. The sentence still seems queer, but more understandably so.

I face the same challenge but on a much broader scale.

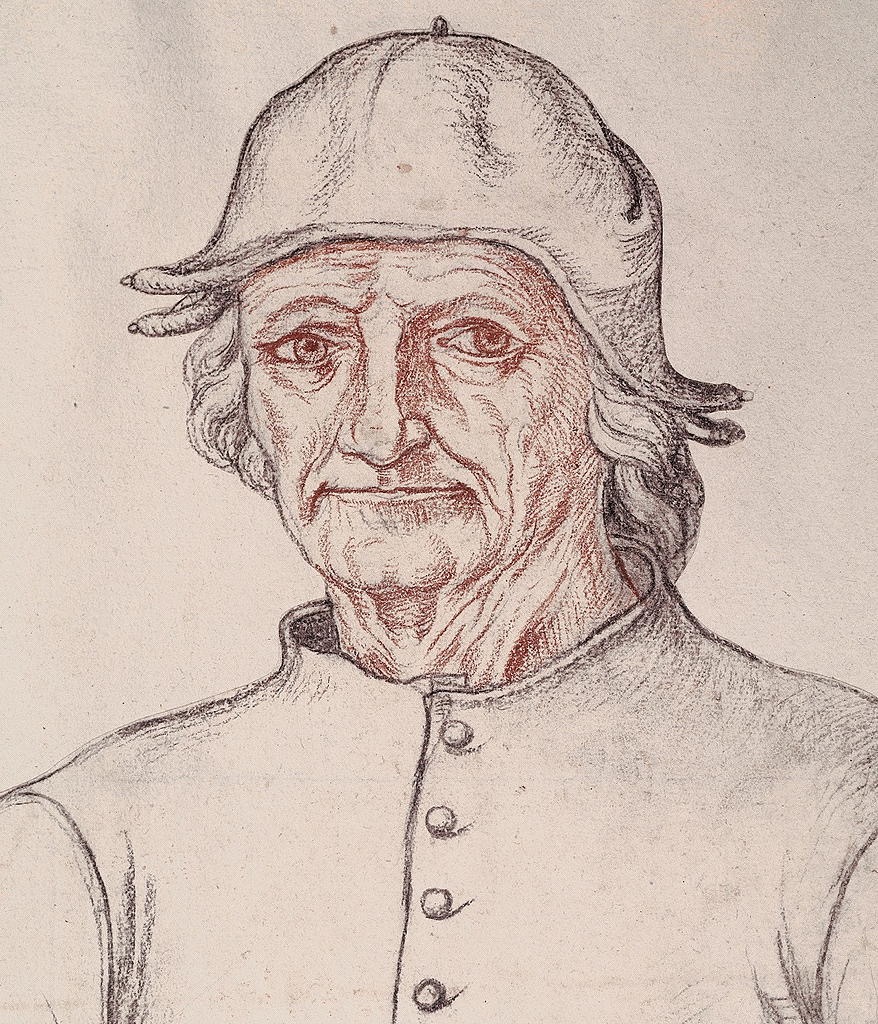

AnSight

Attributed to Jacques Le Boucq: Posthumous Portrait of Hieronymus Bosch (1550)

"The Purpose of Mathematical Programming Is Insight, Not Numbers"

Arthur M. Geoffrion

"Authoring might at essence be nothing more than discovering how to usefully think about Authoring …"

I suspect that the often frantic search for answers amounts to little more than a typical stupid human trick, one of those traps into which we as a species seem to too easily stumble. When a question stumps me, I usually seek an answer to that question, when answer rarely serves as an initial stage of resolution. An answer tends to be something more like the final stage resolution, the end of attempts to resolve, not the go-to first step, yet we persist in first seeking answers. What might we seek instead? Experience alone might have long ago suggested that we'd be much better off seeking insights instead of answers, for, like management professor Arthur M. Geoffrion proposed in his 1976 essay of the same name, The Purpose of Mathematical Programming is Insight, Not Answers. Likewise, the first purpose of resolving questions might well be to somehow stumble upon some useful insight rather than to expect to somehow cobble together some resolving answer from the outset. An insight might lead to resolution while a search for a resolving answer most often produces little more than a frustrating stymie.

As with many things, the long way seems to be the shortcut when attempting to resolve some burning question.

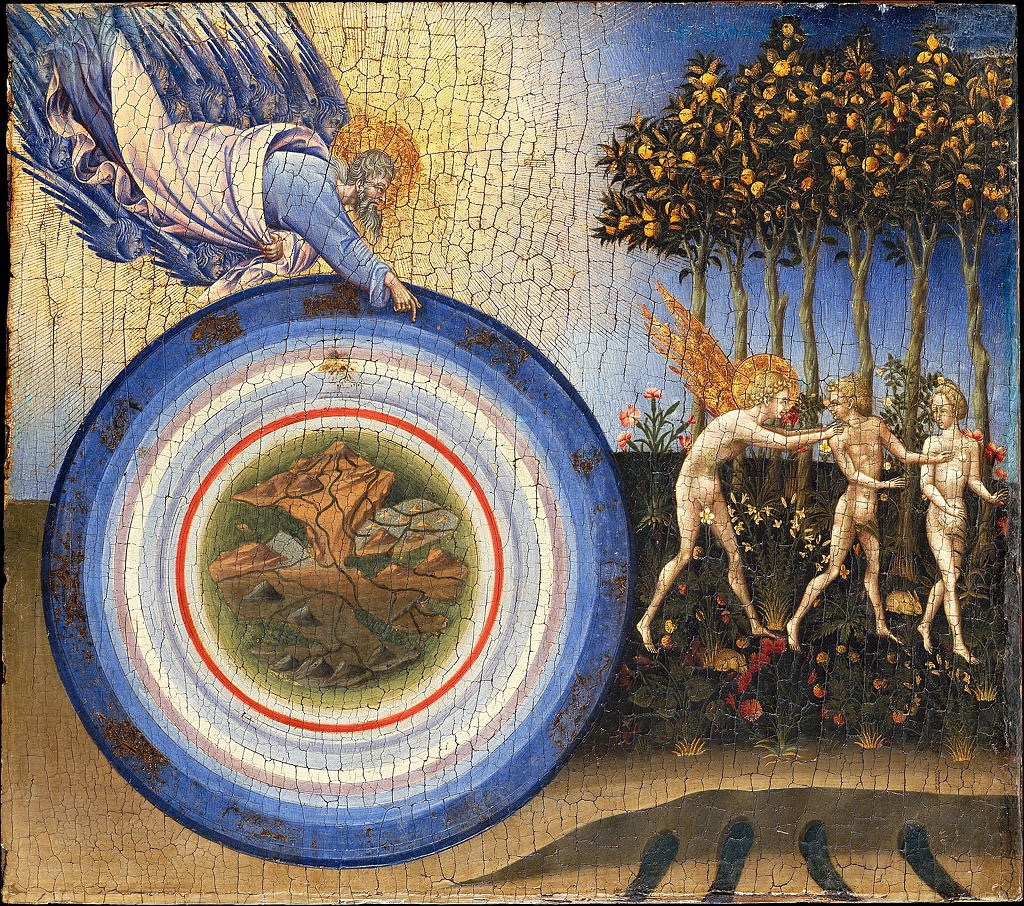

Doubting

The Creation and the Expulsion from the Paradise: Giovanni di Paolo [Giovanni di Paolo di Grazia] (ca. 1438–44)

"I'm gonna take a couple of pills and call myself in the morning."

Following several focused weeks of compiling and Proofing manuscripts, a point came where Doubting kicked in. My Authoring effort, a faith-based initiative if ever one existed, finds its faith sorely tested as its nose slips past the skepticism point on the spectrum to slide into definite Doubting range. Doubting seems a touch deeper than skepticism. While the skeptic holds a possibility, those Doubting carry a conviction which can only be turned by some disconfirming personal experience. Remember the Doubting Apostle Thomas, who refused to believe in the resurrection until he could personally touch Jesus' wounds? The very presence of Jesus might have convinced any skeptic. So much for the often touted benefit of Doubting. Doubting seems more of a hanging judge type of curse than a blessing.

And I would this morning hang the whole Authoring effort from the highest yardarm, if only we had yardarms anymore.

SecondGuessing

Paul Cézanne: The Large Bathers [Les grandes baigneuses] (c. 1894–1906)

"I'll feel grateful for any future acceptance and unsurprised by any upcoming rejections …"

Rather than reassuring myself, Proofing my manuscripts encourages me into SecondGuessing what I thought I was accomplishing when I wrote them. I try to read each cleanly, as if I was just any old reader, but I know my voice too well to avoid jumping ahead. I also know my thinking too well to enter or exit very innocently. I might not remember precisely what I said, but I well understand how I tend to say stuff, and my logic sometimes seems entirely too predictable and precious. I sense the next glibness coming and almost cringe watching it arrive. I've seen my stand-up routine too often to find my jokes funny or insightful anymore.

I wonder what utility my Proofing brings, but I already know the answer.

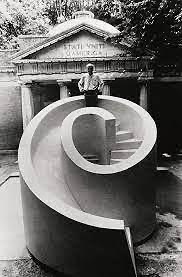

Circuitous

Isamu Noguchi: Slide Mantra (1986)

" … one dare not ever engage in that kind of work anymore."

In this culture, we possess highly evolved methods for streamlining, for 'making efficient.' These tactics underpin what we refer to as Process Improvement, presuming that one improves processes by trimming them down to bare minimums. We prefer methods requiring less time, fewer resources, smaller investments. We're all in for quick and easy, and even feel uneasy when something doesn't seem quick or easy enough, for it seems broken then and in need of 'improvement.' Some activities, however, do not. by their nature, lend themselves to such streamlining. I wrestle with these jobs because efficiency mantras reverberate in my head when I engage in them, telling me that something's wrong, a false positive warning when working with Circuitous processes like Authoring.

I have not yet found the straight or the narrow paths through my Authoring effort.

Enantiodromia

Eduard Tomek: Sea (1971)

"The ancients understood what we forgot."

I don't usually write about whatever we talk about during my weekly Friday PureSchmaltz Zoom Chat. Like all dialogues, one simply must be present in the room, immersed within the context, for the content to make any sense, and attempts to explain what happened to anyone absent from the primary experience seems simply doomed from the outset. Think inarticulate explanation of a movie plot, but I heard myself say something in the thick of yesterday's chat that I think might prove noteworthy, and even germane to my Authoring initiative. I heard myself say that every project ultimately turns into something other than its originating intention before it can be completed. I'd never heard myself (or anyone) state this obvious truth before. Instead, I, like everyone, I suppose, has hung onto the notion that the originating objective accurately represents a project's real purpose, that guiding the effort through to achieve that originating purpose amounted to state-of-the-art 'project management,' when experience might have convinced anyone otherwise. Certainly, many projects have been characterized as failures because they produced something other than their originally expected results, but it might prove useful to wonder if any project of any real complexity had ever succeeded under that strict metric. I doubt it.

The standard practice to counteract this perhaps common phenomena— that projects produce something other than originally intended—has been the final stage politicking typical to every effort of any size, wherein original intentions get reframed to fit within the size shoes the elves managed to produce this time.

AnEmbarrassment

Artemisia Gentileschi - Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (1620s)

"Everything I hold dear will have become as a rusty spoon, leaving little of substance …"

By the time I finish compiling and Proofing my eighteen finished PureSchmaltz Stories manuscripts, I calculate that I'll have accumulated something like six thousand double-sided double-spaced pages, or six reams of printed material. That does not count the two or three or four other odd uncollated manuscripts I have hanging around even further backstage. It also doesn't count the material I continue producing each morning which, by the end of each quarter, adds another three hundred plus pages and yet another "finished" manuscript. Believe me, please, I am not bragging here, but sitting on the edge of a kind of ecstatic despair. Over the forty-five days since I started this Authoring effort, I've compiled five manuscripts and Proofed three, leaving two compiled but not yet proofed and six more to compile and Proof to resolve my current backlog. Try as I might, I cannot seem to proof more than one manuscript per week, for I find that work rather like reading poetry. One cannot speed-read poetry. Proofing my prose induces bouts of ecstatic despair, for the slowly shrinking pile of paper seems an authentic source of both pride and embarrassment for me, one of incalculable wealth.

I had not intended to do this to myself.

Honing

Massimiliano Soldani: The Knife Grinder (c.1700), Albertinum, Dresden

" … sharpening a skill."

Many mysteries have been resolving themselves as I continue my Authoring efforts. I've gotten to the point where I feel as though I can almost make my compiling software do my bidding, though I declare this while keeping the fingers of my right hand crossed and secreted behind my back. No use tempting fate. I feel about as proficient as a novice driver who only drops one in three shifts; more skilled but hardly a master yet. Let's say I'm getting by, and as I begin to get by, my collating effort seems less insurmountable; still at root impossible, but now, surprisingly, less so; a smaller infinity. And with this improvement, the grey cloud which had taken up residence just over my head has begun dispersing, like the fog bank hiding horizons here since Christmas. It's not Spring yet, but the brutal part of the Winter's finished. I sense the brutal part of my Authoring's behind me, too, but behind me like my right hand's behind me, with crossed fingers. Let's say that I've been Honing my craft.

Honing seems an interesting activity because it sits in the often neglected middle ground beyond beginning but before ending.

RipVanSchmaltz

Albertis del Orient Browere: Rip Van Winkle (1833)

"What an overlong and awfully strange nap it's been."

Washington Irving's Rip Van Winkle slept for twenty-five years, at least a third of a lifetime, to awaken into an unrecognizable world where children had become adults and adults, elderly or dead. He, himself, had grown a long white beard and moved with unaccustomed difficulty. I can speak anecdotally, from my own experience, to report that one need not doze for twenty-five years to experience a Rip Van Winkle effect. I'm convinced that no wakefulness exists that's powerful enough to stave off this result, for this world seems in constant flux and moves indifferent to us. Focusing upon any piece of it will leave one out of synch with other parts, and there exists altogether too many parts for any one of us to ever even hope to keep up with their fluxes. The Muse and I went on a thirteen year exile only to return to a place essentially unrecognizable, then we set about refurbishing, which further erased many formerly reliable context markers. We returned to a place we'd never before inhabited to carry on a life that had been more than merely disrupted.

The first few years of our exile, we were able to easily maintain the dream, by which I guess I mean that we were already sleeping.

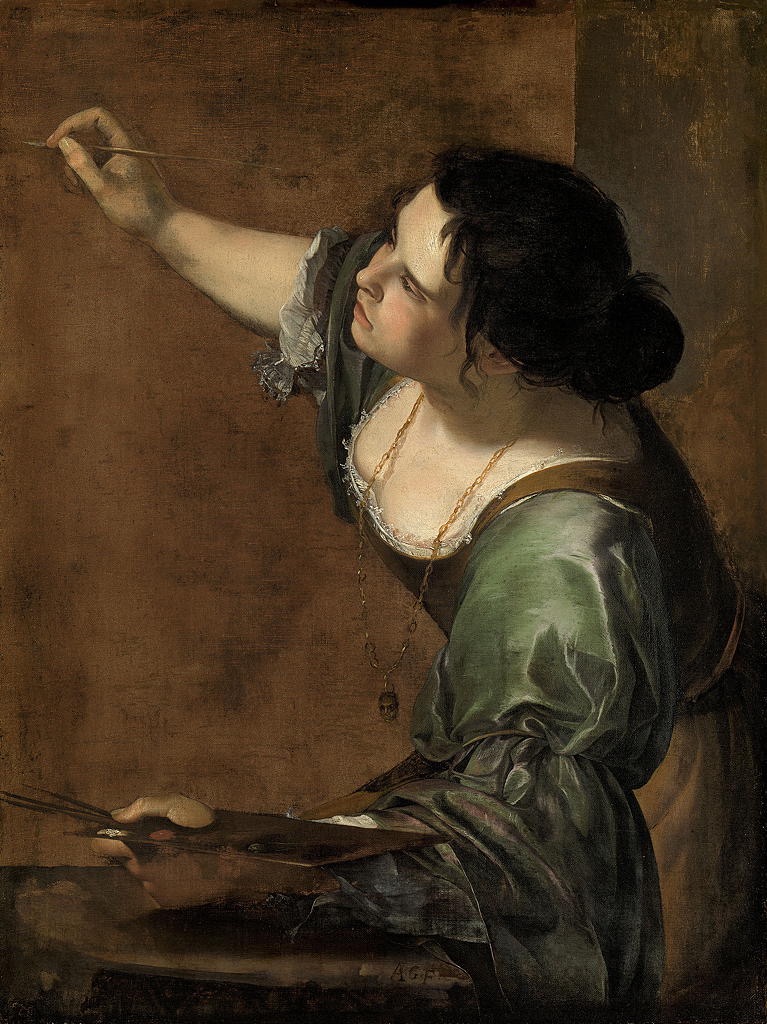

SpurtyWork

Artemisia Gentileschi:

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1638–39)

"I hope to stumble upon some insight …"

I might classify work as belonging to two general classes: steady work and SpurtyWork. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors avoided steady work, but in more modern times it has become the dominant form, usually dispatched in shifts, often extending over many contiguous hours, days, weeks, months, years, and careers. SpurtyWork exclusively occurs in bursts, often separated by lengthy idle or distracted periods, time spent away from focusing upon the effort. Steady workers and SpurtyWorkers have always held contentious, often contemptuous opinions of each other. To the dedicated steady worker, SpurtyWorkers seem frivolous and lacking in any primary focus. To SpurtyWorkers, the steady workers seem like wage slaves, masochistically mortgaging their lives to the unforgiving time clock and unrelenting seasons. Steady workers might reasonably aspire to efficient performances that could not possibly even compute when considered from within a SpurtyWork context. Steady workers might experience flow. SpurtyWorkers produce in fits, starts, and stalls, with apparently heavy focus upon stalling, idling. Farmers traditionally complained about hunter-gatherers' lax habits, thinking them lazy, though a hunter-gather could typically satisfy their needs working many fewer hours and so adopted lifestyles dominated by leisure rather than labor. Steady workers are Puritans, SpurtyWorkers, Bacchanalian, at least in each others' opinion.

Authoring's inescapably SpurtyWork.